Physical activity levels and perceived barriers to exercise participation in Irish General Practitioners and General Practice trainees

D M. Keohane, N A. Mulligan, B Daly

South West Specialist Training Programme in General Practice, Sòlas Building, ITT North Campus, Tralee, Co. Kerry, Ireland.

Abstract

Physical activity is a pillar stone of health promotion and primary care is perfectly poised to disseminate this message. Primary care however, often fails in this regard, missing an opportunity to promote a simple intervention that is effective, free and easily accessible. This study aimed to determine physical activity levels in Irish General Practitioners and General Practice Trainees in addition to describing the barriers to exercise that exist amongst this cohort. This cross-sectional study of Irish General Practice trainers and trainees captured a categorical record of physical activity as well as a qualitative measure of the perceived barriers to exercise. Only 49% (n=107) of those studied engaged in health enhancing physical activity while 20% (n=44) were completely inactive. Sixty percent (n=131) demonstrated excessively sedentary behaviour. The greatest barriers to exercise were time expenditure and exhaustion. General practitioners and trainees are more likely to engage with promoting physical activity as a health intervention if its benefits are clearly demonstrable in their own lives. This established trend of inactivity needs to be reversed if physicians wish to realise significant health benefits in their own lives and achieve substantial change in the health behaviours of their patients.

Introduction

Strong evidence suggests that increased physical activity can reduce the risk of developing certain diseases such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and some cancers1. Both international and national guidelines recommend that all adults should be physically active for at least 30 min per day, preferably 7 days a week2. Despite this recommendation a considerable proportion of the population are inactive and therefore at an increased risk of adverse health outcome2.

Advocating a healthy lifestyle is one of the key components of General Practice. Interestingly, one of the strongest predictors of this health promotion counselling by physicians is adopting a healthy lifestyle themselves3-5. This is because many doctors report difficulty in recommending measures that do not apply to themselves5. A study by J. McKenna et al showed that General Practitioners (GPs) were more likely to promote exercise if they personally engaged with regular exercise (OR = 3.19, 95% CI 1.96 to 5.18)5. Despite this levels of physical activity and barriers to GPs achieving international recommendations have not been established. Much of the research to date has looked at the relationship between physicians and "exercise promotion", but none have specifically explored the association between GPs and "exercise participation". These studies have essentially looked at the effect and ignored the cause of poor health promotion of physical activity in primary care. With health care under significant pressures, physical activity is a simple intervention with a clear evidence base that is free, easily accessible and non-discriminatory. This study aims to explore physical activity levels in Irish General Practitioners and General Practice Trainees in addition to investigating the perceived barriers to exercise that exist amongst this cohort.

Methods

This study was cross-sectional in design. The study population included all General Practice trainees and General Practice trainers in the Republic Of Ireland. The study employed two internationally validated6,7 questionnaires that were delivered via a web-based survey platform. The physical activity tool was the self administered International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The second validated physical activity tool used was the Exercise Benefits/Barriers scale (EBBS) of which only the barriers component was employed. The barrier component includes 14 barrier items categorized into four subscales, which provide a validated analysis of the intended study group. Participant demographics were also collected. From each individual physical activity record a categorical score, measured in low, moderate and high levels of physical activity was calculated. If any data was missing from the time or day variables, then this case was removed. All data was coded in accordance with the guidance set out in the IPAQ analysis tool.

The IPAQ results were computed to classify individuals into three levels of physical activity. The proposed levels were inactive, minimally active and health enhancing physical activity (HEPA) active. Algorithmic analytical steps were utilised, guided by the questionnaire analysis tools, to establish those who had sufficient physical activity and high active categories. Finally time spent in sedentary activity was calculated in hours. The Barriers to exercise instrument (Barriers Scale) has a four-response, forced-choice Likert-type format with responses ranging from four (strongly agree), to one (strongly disagree). If more than five percent of the items were unanswered, the response was discarded. The Barriers Scale has a score range between 14 and 56. The higher the score the greater the perception of barrier to exercise. The 14 barrier items were further categorised into four subscales: exercise milieu; time expenditure; physical exertion; and family discouragement. The greatest perceived barrier of the four subsets was assessed by multiple paired sample t-tests to identify any significant differences between the subscales. An alpha of 5% was maintained to control against an inflated alpha and an increased possibility of type-1 errors due to these multiple comparisons. Tests for normality including, Q-Q plots and Shapiro Wilks confirmed the data were normally distributed and supported the appropriate use of parametric statistical tests.

Results

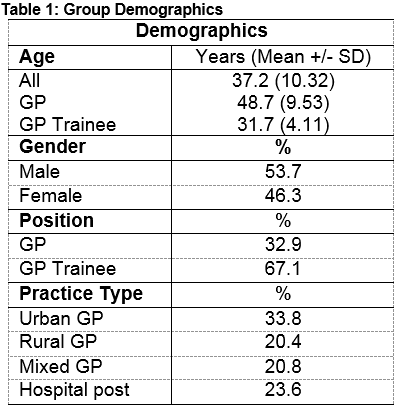

There were a total of 246 respondents in the preliminary analysis, 219 of which eligible for inclusion. Twenty-seven respondents were excluded due to missing data fields. The overall response rate was 28% (27% for GP trainees and 29% for GP Trainers). The response group consisted of 33% General Practitioners and 67% GP trainees. Demographics of the group is summarised in Table 1. Of this group, 21% of participants were deemed “inactive”, 30% deemed “minimally active” and 49% were found to be “HEPA (health enhancing physical activity) active”.

Levels of activity

In comparing levels of activity versus gender, females were more likely to be inactive (p<0.05). In comparing General Practice type (urban vs. rural) versus levels of activity, there was no significant difference noted. However in relation to hospital based GP trianee versus community based doctors, a statistically significant difference was noted (p<0.05) with more hospital based GP trainees taking part in a greater levels of activity. When analysing the professional role (GP Vs GP Trainee) and the level of activity, no significant difference was found.

Sitting time

In relation to time spent doing sedentary activity, 60% of the group spent 7 hours or more sitting on a daily basis. Sixteen percent spent less than or equal to 4 hours of sedentary activity with the remaining 24% between 4 and 7 hours. There was no significance demonstrated between male and female respondents in relation to time spent sitting (p=0.61). However there was noted to be a statistically significant difference between both hospital based trainees and GP Practices of any type (rural, urban and mixed) (p<0.05) and between qualified GP’s and GP trainees (p<0.05).

Age

Age did not predict the GPs' exercise category or sitting time. Specifically, it was not deemed to be a factor in these two independent variables.

Perceived barriers to exercise

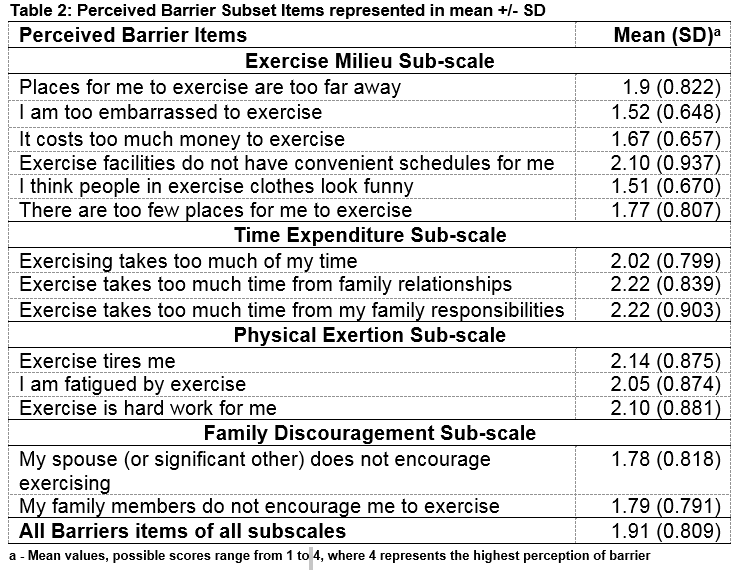

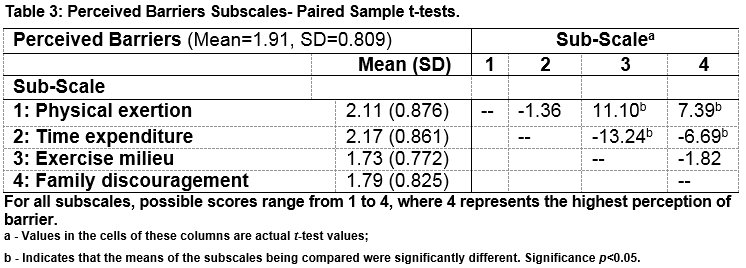

The greatest barrier on the perceived barrier subscale was time expenditure, followed by physical exertion, family discouragement and exercise milieu. This is summarised in mean +/- SD in Table 2. Time expenditure was rated significantly higher than all barrier subscales with the exception of physical exertion. Physical exertion rated significantly higher as a perceived barrier than both the family discouragement and exercise milieu subscales. There was no significant difference between family discouragement and the exercise milieu subscale. The exercise milieu subscale included the perceived barriers of inconvenience, cost and preconceptions about exercise.

Independent sample t-test for gender, practice type (urban, rural, mixed, hospital), professional role (General Practitioner, GP trainee, hospital post or other) and the barriers subscales did not reveal any significant difference. Rural practice Doctors perceived inconvenient exercise facility schedules to be a significantly greater barrier to physical activity than their urban colleagues (p=0.003). The internal consistency of the barriers scale for this sample was 0.92. Paired sample t-test comparisons of the barrier subscales are summarised in Table 3.

Discussion

It was discouraging to see that less than 50% of General Practitioners and General Practice trainees studied were engaging in health enhancing physical activity. Additionally, over 20% of all respondents were physically inactive with this trend being significantly higher in females. When interpreting this data it is important to note the response rate was 28%. While this response was anticipated and typical of electronically distributed, questionnaire-based studies17, it is likely to have introduced some selection bias. Sitting time was exceptionally high within the group with over 60% of respondents claiming to sit for 7 hours or greater per day. Sitting time is independent of physical activity as a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcome16. Therefore, combining excessive sitting time and physical inactivity cumulatively increases the risk of adverse health outcome.

Time constraint was the greatest barrier to exercise within this group. Interestingly, studies have shown that time is also the limiting factor in exercise promotion and counselling14,15. This was independent of gender, role (GP Trainee, GP) and practice type (urban, rural, mixed, hospital post). As a group, GPs devote much of their day consulting on the health consequences of physical inactivity yet it would appear from this study that some are short on time when it comes to participating themselves. This is despite clear evidence of benefit. General Practitioners need to be mindful of the ever increasing demands being made of their time and must be conscious of their own health needs. This is likely to benefit their patients in turn.

The results of the perceived barrier subscales were consistent across the entire cohort irrespective of the difference that exists within the group such as practice location, professional role or gender. This is noteworthy, as the barriers of time-expenditure and physical exertion are perceived by the entire group, regardless of the disparities that exist within the group. Going forward a clear and targeted strategy is needed to address this issue.

As a sedentary profession with high levels of inactivity, General Practitioners are clearly at an increased risk of the very same health consequences they aim to prevent in their patients. This study has however, for the first time revealed the perceived barriers to exercise that exist amongst General Practitioners and General Practice trainees. These barriers need to be addressed to bring about a significant change in health behaviour. Furthermore, the study also highlighted that 50% of this group fail to reach health enhancing physical activity levels and over 60% sit for more than seven hours per day. GPs both individually and collectively need to adopt a proactive stance on physical activity participation in addition to promotion in order to bring about personal change as well as change in the health behaviours of their patients.

Ethical Approval:

Ethical approval was sought and sanctioned prior to initiating data collection through the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC) of the Cork University Teaching Hospitals, Ireland.

Funding:

Nil

Conflicting Interests:

Nil

Correspondence:

Dr. David M. Keohane , Department Of General Practice, C/O Ms Ita Kirwan, Sòlas Building, ITT North Campus, Tralee, Co. Kerry Ireland

Email: [email protected]

References

1. World Health Organisation (2002). The World Health Report 2002. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life (WHO, Geneva). http://www.who.int/whr/2002, (accessed 2 Oct 2016)

2. World Health Organisation (2010). Global recommendations on physical activity for health (WHO, Geneva). http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity, (accessed 2 Oct 2016)

3. Harsha DM, Saywell RM, Thygerson S, Panozzo J. Physician factors affecting patient willingness to comply with exercise recommendations. Clin J Sport Med. 1996;6(2):112-8.

4. Frank E, Kunovich-Frieze T. Physicians' prevention counseling behaviors: current status and future directions. Prev Med. 1995;24(6):543-5.

5. McKenna J, Naylor PJ, McDowell N. Barriers to physical activity promotion by general practitioners and practice nurses. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32(3):242-7.

6. Hagströmer M, Oja P, Sjöström M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):755-62.

7. Sechrist KR, Walker SN, Pender NJ. Development and psychometric evaluation of the exercise benefits/barriers scale. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10(6):357-65

8. Patra L, Mini GK, Mathews E, Thankappan KR. Doctors' self-reported physical activity, their counselling practices and their correlates in urban Trivandrum, South India: should a full-service doctor be a physically active doctor? Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(6):413-6.

9. Lobelo F, Duperly J, Frank E. Physical activity habits of doctors and medical students influence their counselling practices. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(2):89-92.

10. Lobelo F, de Quevedo IG. The Evidence in Support of Physicians and Health Care Providers as Physical Activity Role Models. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;1.55982761352012E15.

11. Fraser SE, Leveritt MD, Ball LE. Patients' perceptions of their general practitioner's health and weight influences their perceptions of nutrition and exercise advice received. J Prim Health Care. 2013;5(4):301-7.

12. Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Craig CL, Bouchard C. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(5):998-1005.

13. Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38(3):105-13.

14. Pender NH, Sallis JF, Long BJ. Health care provider counseling to promote physical activity. In: Dishman RK, Advances in Exercise adherence, 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1994:213–35.

15. Winzenberg T, Reid P, Shaw K. Assessing physical activity in general practice: a disconnect between clinical practice and public health? Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(568):e359-67.

16. Lovell GP, El Ansari W, Parker JK. Perceived exercise benefits and barriers of non-exercising female university students in the United Kingdom. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(3):784-98.

17. Shih TH, Fan X. Comparing Response Rates from Web and Mail Surveys: A Meta-Analysis. Field Methods. 2008;20 (3):249 - 27

P690