Awareness of Medical Fitness to Drive Guidelines among Occupational Physicians and Psychiatrists

M Ryan1, R McFadden1, E Gilvarry2, R Loane3, D Whelan4, D O’Neill1

1 National Office for Traffic Medicine, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, Dublin 2.

2 Northumberland, Tyne & Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle Addictions Service, Plummer Court, Carliol Place, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 6UR.

3 College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, 5 Herbert St, Grand Canal Dock, Dublin 2.

4 Faculty of Occupational Health, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, Dublin 2.

Abstract

Irrespective of national guidelines for medical fitness to drive, this study investigated the cumulative expert wisdom of clinicians regarding minimum periods of driving cessation required for patients suffering from conditions that can impair driver capability. Occupational Physicians (196) and Psychiatrists (103) completed an online questionnaire. For private motorists, the modal response for anxiety and depression favoured clinical discretion, followed by three month cessations for hypomania, acute psychosis, schizophrenia and alcohol dependence and six weeks for alcohol misuse/dependence. For professional drivers the modal value for anxiety and depression was three months, rising to six months for hypomania, psychosis and schizophrenia and 12 months for both alcohol misuse/dependence. Chi-square test results indicated statistically significant differences in clinical opinion between Occupational Physicians and Psychiatrists regarding driving cessation times for drivers suffering from psychiatric and alcohol misuse conditions except for alcohol dependence. Further studies are warranted to investigate these issues in more depth.

Introduction

Theoretical models1 and a wealth of international research2 indicate that driver capability is a major predictor of traffic risk. Driver fitness in Europe is governed by EU law and regulations made locally in individual jurisdictions. In Ireland, the Sláinte agus Tiomáint Medical Fitness to Drive Guidelines3, developed by the National Office for Traffic Medicine and published by the Road Safety Authority, represent an interpretation of these laws and the best available evidence from research in traffic medicine. These guidelines, which reflect similar guidelines produced by the UK Driver and Vehicle Licencing Agency (DVLA)4, serve to increase awareness among medical professionals and the wider community about fitness to drive. They summarize the criteria for medical certification of two classes of drivers; Group 1 (cars and motorcycles) and Group 2 (trucks and buses).

A range of research studies indicate that doctors have inadequate knowledge of their national or state medical fitness to drive (MFTD) guidelines5,6, although this can be improved by pro-active dissemination of national guidelines and an extensive education programme in traffic medicine8. However, few (if any), studies have attempted to investigate the cumulative wisdom and experience of clinical MFTD judgement among experienced clinicians. This approach may be particularly helpful in aspects of MFTD where there is little by way of empirical evidence to support guideline development, for example, with psychiatric illness and alcohol and substance abuse.{Kahvedžić A, 2015 #2}

The aim of the current study was to broaden our understanding of the insights arising from clinical practice/opinion of occupational physicians and psychiatrists. Whereas current MFTD guidelines in Ireland and the UK specify minimum periods necessary before individuals living with certain types of medical conditions (e.g. alcohol misuse or dependence), we were interested in gauging the clinicians’ beliefs and practices when deciding on minimum periods necessary for individuals suffering from the following six types of medical conditions; severe anxiety states and depressive illness, hypomania, acute psychosis, chronic schizophrenia, and also alcohol misuse and alcohol dependence. The basis for the choice of minimum periods of driving cessation relies more on tradition rather than on an evidence base. However, if the duration of driving cessation is unduly prolonged, the driver may suffer from occupational and social distress from restricted mobility, which may in turn aggravate the underlying psychiatric condition. There is also some concern that such guidelines may be ignored in clinical practice. It is noteworthy that in Australia the minimum cessation period for Group 1 drivers is left to clinical judgment9.

Some divergence is evident in guidance provided in the UK DVLA and Irish MFTD guidelines. The MFTD guidelines state that where persistent alcohol misuse has been confirmed by medical enquiry, driving should cease until a minimum three-month period (Group 1 drivers) and a minimum period of 12 months (Group 2 drivers) of controlled drinking or abstinence has been attained. In the case of alcohol dependence the minimum cessation period of 6 months (Group 1) and three years (Group 2) is stipulated. In comparison, the DVLA guidelines stipulate an abstinence from driving of 6 months (Group 1) and 12 months (Group 2) for drivers who misuse alcohol and minimum abstinences of 12 months (Group 1) and 3 years (Group 2) for alcohol dependent drivers.

Methods

An online survey, consisting of 30 questions, assessed professional opinion about medical fitness to drive with respect to Group 1 and Group 2 drivers among Occupational Physicians and Psychiatrists in the UK and Ireland. Respondents were asked to indicate the minimum period of wellness and stability (if any) that should, in their clinical judgment, be present prior to resuming driving in relation to six conditions; severe anxiety states and depressive Illness, hypomania/mania, acute psychosis, chronic schizophrenia or relapsing/remitting schizophrenia, alcohol misuse and alcohol dependence. A five-point scale was used to measure responses related to Group 1 drivers (1 = No minimum period, at clinician discretion, 2 = 1 month, 3 = Six weeks, 4 = 3 months, 5 = 6 months). An expanded nine-point scale was used for Group 2 drivers (6 = 12 months, 7 = 18 months, 8 = 24 months and 9 = 36 months). Clinicians were instructed to make their judgement without reference to existing guidelines.

Results

Participants

The total number of respondents invited was: 21,000 from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (London), 1,043 from the College of Psychiatrists (Ireland), 117 from Royal College of Occupational Health, and 690 from the Irish Society for Occupational Health and licentiates, members and fellows in Occupational Health at the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI). Three hundred and forty-five Occupational Physicians and Psychiatrists accessed the questionnaire, however as 38 (11%) of these did not answer a substantial number of the questions the data they provided was not included in subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 299 participants, 196 (66%) were Occupational Physicians and 103 (34%) were Psychiatrists. In terms of gender, 163 (55%) of participants were men and 117 (39%) were women and 19 (6%) did not indicate gender. Of the psychiatrists, 54% were women and 46% were men. Of the Occupational Physicians, 36% were women, whereas 64.5% were men.

Minimum period necessary before resuming driving

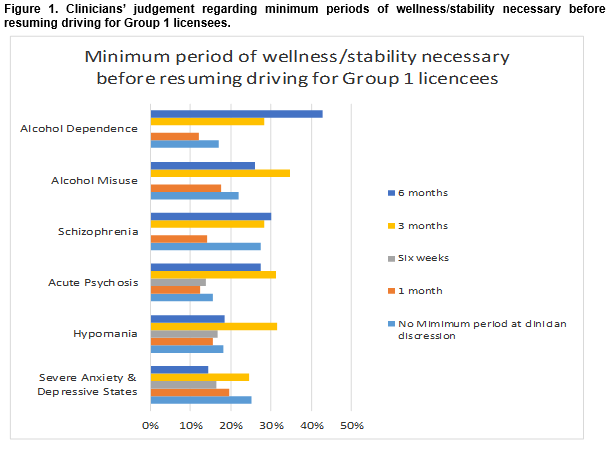

In the case of Group 1 licensees, the following percentage of clinicians from both disciplines indicated that the minimum period of wellness/stability necessary before resuming driving should be at clinician discretion; Severe anxiety states and depressive illnesses (n(25%)), hypomania (n(18%)), acute psychosis (n(15.5%)), schizophrenia (n(27.5%)), alcohol misuse (n(21.8%)) and alcohol dependence (n(16.9%)) (Figure 1).Whereas clinician discretion was the modal response in relation to anxiety and depression, three months was the modal response for cases of hypomania, acute psychosis, schizophrenia and alcohol dependence and six weeks was the modal recommendation where alcohol misuse was diagnosed.

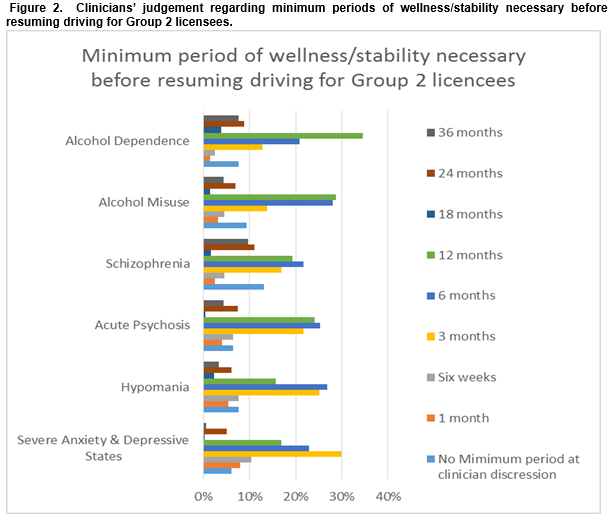

Clinical judgements in relation to Group 2 licensees were predictably more conservative. For instance, the percentages of respondents who believed that no minimum period should be stipulated, but that the minimum periods of wellness/stability necessary before recommending driving should be left to clinical discretion was considerably lower, i.e. Severe anxiety states and depressive illness (n(6.1%)), hypomania (n(7.7%)), acute psychosis (n(6.4%)), schizophrenia (n(13.1%)), alcohol misuse (n(9.3%)) and alcohol dependence (n(7.7%)) (Figure 2). The modal value for anxiety and depression was three months, this rose to six months for hypomania, psychosis and schizophrenia and 12 months for both alcohol misuse and dependence.

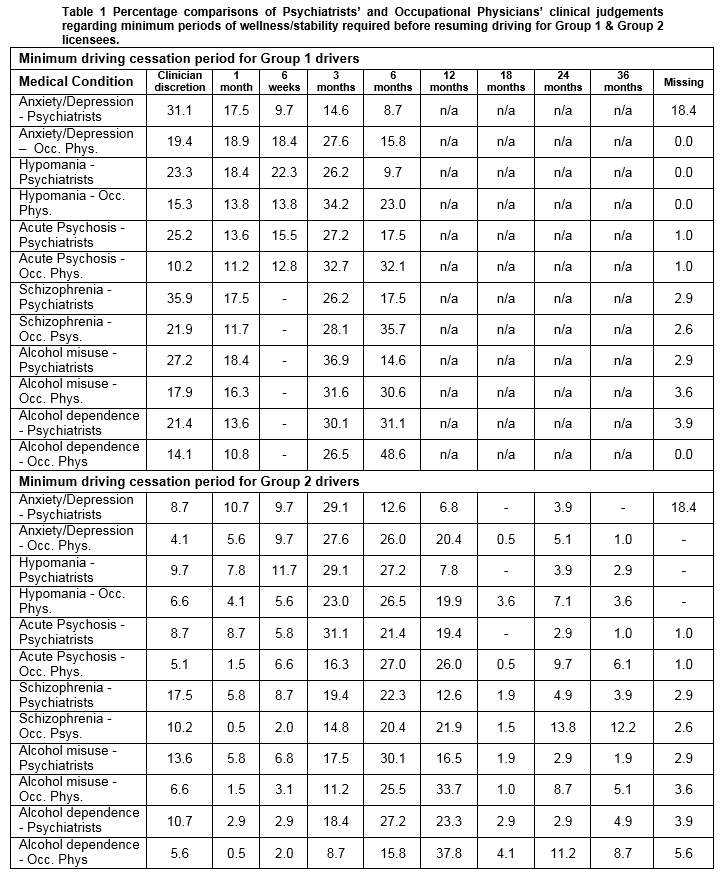

Preliminary inspection of the data suggested that there were some differences of opinion between the Occupational Physicians and the Psychiatrists surveyed regarding the minimum periods of wellness/stability required before resuming driving for Group 1 (private) and Group 2 (professional) drivers (Table 1).

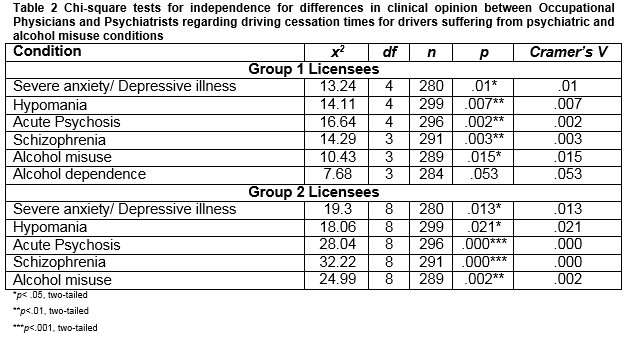

When treating patients in Group 1, a higher percentage of Psychiatrists than Occupational Physicians favoured the use of clinical discretion for all 6 conditions that featured in this study. Conversely, a higher percentage of Occupational Physicians tended to favour 6 month cessations in comparison to the clinical judgement of the Psychiatrists. Whereas a similar pattern emerged in the context of Group 2 licensees, the percentage differences were noticeably smaller. Subsequently, a series of a chi-square tests for independence was conducted to explore the nature of these differences (see Table 2).

The results showed that these differences were statistically significant for all conditions of interest in this study with the exception of alcohol dependence However, as indicated by the Cramer’s V statistic, these effects were quite small.

Discussion

The results from this study suggest a high degree of variability among clinicians with regard to both the principle of a defined minimum period of driving cessation with a range of psychiatric and alcohol dependence conditions and also to the minimum time period in each instance. For Group 1 drivers in particular, between one-sixth and one quarter of clinicians indicate that there should not be a defined minimum but rather that the clinician should make an individual determination. Perhaps of more significance is that the combination of those who opt for clinical discretion and the modal value of the minimum time of the other clinicians is significantly less than the current Irish and UK DVLA guidelines in relation to minimum periods for alcohol dependence and misuse. This should prompt a reconsideration of the validity of the existing guidelines for these conditions. Further studies are required into the actual advice given in clinical setting to consecutive series of drivers presenting with alcohol misuse and dependence as well as naturalistic studies of crash outcomes for these groups of drivers.

A similar divergence is seen for Group 1 drivers with regard to the UK guidelines for the other conditions, although the Irish guidelines have moved to clinician discretion since 2016. While road safety is a key consideration for MFTD, the importance of transport as a mediator of psychosocial and economic well-being is increasingly recognized as an important consideration in making these decisions10. It is clearly important that MFTD assessment maintains a due balance between mobility and safety, and the insights of experienced clinicians into the variability of prognosis and insight for drivers with mental health and substance abuse/dependence problems must form a key element of developing guidelines that are acceptable to all stakeholder in the transport and road safety system.

The limitations of this research relate to the relatively low response rate, common in internet-based surveys. However, as this is the first survey of its kind in the biomedical literature, we feel that it represent an important first step in teasing out MFTD guidelines for an important range of mental health conditions which represent a due combination of evidence and clinical experience.

Correspondence:

Prof Desmond O’Neill, Director, National Office for Traffic Medicine, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, Setanta House, Setanta Place, Dublin 2.

Email: [email protected]

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Fuller, R. (2005). Towards a general theory of driver behaviour. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 37(3), 461-472. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.11.003

2. Petridou, E, Moustaki, M. Human factors in the causation of road traffic crashes. Eur J Epidemiol (2000) 16:819. doi:10.1023/A:1007649804201

3. Slainte agus Tiomaint Medical Fitness to Drive Guidelines (2016). Retrieved 16/12/2016 from http://www.rsa.ie/Documents/Licensed%20Drivers/Medical_Issues/Sl%C3%A1inte_agus_Tiom%C3%A1int_Medical_Fitness_to_Drive_Guidelines.pdf

4. UK Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. Assessing fitness to drive: a guide for medical professionals. Retrieved 16/12/2016 from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/assessing-fitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical-professionals

5. Kelly R, Warke T, I. S. Medical restrictions to driving: the awareness of patients and doctors. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:537-9.

6. Thompson P, Nelson, D. DVLA regulations concerning driving and psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Bull. 1996;20:323-5.

7. Morgan JF. DVLA and GMC guidelines on "fitness to drive" and psychiatric disorders: knowledge folowing an educational campaign. Med Sci Law. 1998;38:28-33.

8. Kahvedžić A, McFadden R, Cummins G, Carr D, D. ON. Impact of new guidelines and educational program on awareness of medical fitness to drive among general practitioners in Ireland. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2015;16(6):593-8.

9. Austroads, NCT Australia. Assessing fitness to drive for commercial and private vehicle drivers. 2016. Retrieved 23/12/2016 from http://www.austroads.com.au/drivers-vehicles/assessing-fitness-to-drive

10. Oxley J, Whelan M. It cannot be all about safety: The benefits of prolonged mobility. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2008: 9, 367-378. doi:10.1080/15389580801895282

(P653)