Benign Intracranial Hypertension Necessitating Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Insertion Secondary to Growth Hormone Therapy

M. Mahon1 D. Cody2

1. Trinity College Dublin

2. Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital Crumlin (OLCHC)

Abstract

Presentation

Constant bilateral frontal headache associated with early morning awakenings, two episodes of vomiting and blurred vision.

Diagnosis

Benign Intracranial Hypertension.

Treatment

Repeat Lumbar Punctures were performed. GH was stopped and acetazolamide commenced. Later requiring VP shunt due to refractory symptoms with full resolution of symptoms.

Conclusion

Surgical management involving shunt procedures are reserved for refractory cases and are highly effective at resolving intractable symptoms.

Case Report

A 14 year old female was referred to Endocrinology out-patient department for assessment of short stature. A karyotype confirmed 45X karyotype consistent with Turner syndrome. On examination, the patient had a weight of 68.8 kg (>80th centile), height of 138.6 cm (<5th centile) with a body mass index (BMI) of 35.8 (>95th percentile). Ultrasound of abdomen and pelvis demonstrated pre-pubertal uterus and small ovaries. Raised pituitary gonadotrophins with LH of 14.6 IU/l and FSH of 111 were consistent with a primary gonadal failure picture.

The decision was made to commence her on growth hormone (GH) therapy for treatment of her short stature secondary to Turner Syndrome. Initially she was started on 1.0 mg for two weeks then increased to 1.8 mg as per dosing schedule.

Five weeks later the patient presented with worsening headaches. A constant bilateral frontal headache associated with early morning awakenings, two episodes of vomiting and blurred vision was recorded. Advice was given to reduce the dose and referral made to ophthalmology to monitor for benign intracranial hypertension.

Two weeks later the patient represented to ED requiring admission. A lumbar puncture (LP) was performed and an opening pressure of 43 cm H20 documented, relative to a normal opening pressure of 20 cm H20 for her age. Review by ophthalmology showed bilateral small discs with blurring of the nasal margins. Vision was otherwise normal. These findings were consistent with benign intracranial hypertension. GH was stopped and acetazolamide 125 mg BD commenced increasing to 500 mg BD as tolerated.

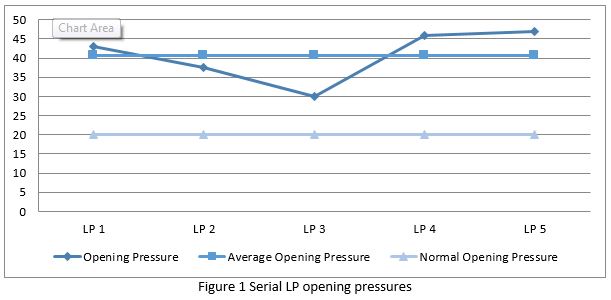

Over the next three months the patient required a further five admissions for LP under general anaesthetic due to persistent symptoms. Opening pressures ranged from 30-47 cm H20 with a mean of 40.7 cm H20 (Fig. 1). After each LP the symptoms resolved immediately but later recurred. At this point, and following review by Neurosurgery, a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt was then inserted with full resolution of symptoms. However the VP shunt was removed within one week due to complications of vomiting and disequilibrium with no recurrence of the prior symptoms. The decision was made not to rechallenge with GH treatment.

Discussion

Discussion

A longstanding association exists between recombinant GH and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). Most cases of IIH within the paediatric cohort have an identifiable aetiology; including endocrine abnormalities, medications, viral infection or systemic conditions. Documented reports also suggest an incidence greater in young adolescents aged 12-15 and those who are overweight or obese (BMI >95th centile)1. Interestingly, a moderate weight gain of 5-15% in the year prior to presentation has been attributed to increased risk of developing IIH.2.

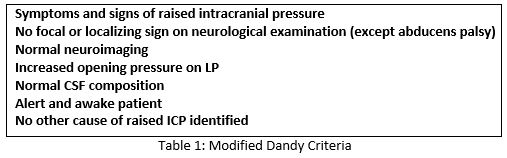

IIH is defined as an elevated intracranial pressure, normal cerebrospinal fluid composition and normal or reduced ventricular volume on neuroimaging 3. The diagnosis is made according to the modified Dandy Criteria (Table 1). Despite an existing underlying aetiology the mechanism has not been fully elicited in GH-treated patients. It is proposed however, that GH levels become elevated in the CSF during treatment, activating the choroid plexus, which has a significant concentration of IGF-1 receptors causing a transient increase in CSF production4.

Headache, as in our case, is the most common presenting complaint in children developing IIH5. Other presentations include visual disturbance; blurred or double vision, nausea or vomiting and with increasing pressure abducens nerve palsy presents as the most frequent focal neurological deficit5. As younger children may have difficulty in appreciating their symptoms, they may instead simply present irritable.

Due to the ophthalmological complications routine monitoring for symptoms and signs of raised intracranial pressure is advised with fundoscopic examination prior to initiating and at regular intervals during GH therapy. The majority of IIH cases in the pediatric cohort will respond to medical management with resolution of symptoms .This involves cessation of hormone replacement and commencing acetazolamide. Surgical management involving shunt procedures are reserved for refractory cases and are highly effective at resolving intractable headache with relief persisting for up to 20 years6. Lumbaroperitoneal (LP) shunts are preferred to ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts as the ventricles are usually not enlarged and the procedure is entirely extra-cranial7. The use of LP shunts is well documented however, associated with a high revision rate6.

VP shunt insertion, as in our case, is an effective method in managing refractory IIH8,9. It is therefore advised to have early consideration for shunt insertion after multiple LP procedures.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Corresponding Author

Mark Mahon,

Trinity College Dublin

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Ko MW, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Hormone research in paediatrics. 2010;74(6):381-9.

2. Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL, Moster ML, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Lee AG, Wall M, Kardon R, Acierno MD. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Apr 1;143(4):635-41.

3. Rogers AH, Rogers GL, Bremer DL, McGregor ML. Pseudotumor cerebri in children receiving recombinant human growth hormone. Ophthalmology. 1999 Jun 1;106(6):1186-90.

4. Crock PA, McKenzie JD, Nicoll AM, Howard NJ, Cutfield W, Shield LK, Byrne G. Benign intracranial hypertension and recombinant growth hormone therapy in Australia and New Zealand. Acta Paediatrica. 1998 Apr 1;87(4):381-6.

5. Malozowski S, Tanner LA, Wysowski DK, Fleming GA, Stadel BV. Benign intracranial hypertension in children with growth hormone deficiency treated with growth hormone. The Journal of pediatrics. 1995 Jun 1;126(6):996-9.

6. Maher CO, Garrity JA, Meyer FB. Refractory idiopathic intracranial hypertension treated with stereotactically planned ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. Neurosurgical focus. 2001 Feb;10(2):1-4.

7. Abubaker K, Ali Z, Raza K, Bolger C, Rawluk D, O'Brien D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: lumboperitoneal shunts versus ventriculoperitoneal shunts–case series and literature review. British journal of neurosurgery. 2011 Feb 1;25(1):94-9.

8. Heyman J, Ved R, Amato-Watkins A, Bhatti I, Naude JT, Gibbon F, Leach P. Outcomes of ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion in the management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in children. Child's Nervous System. 2017 Aug 1;33(8):1309-15.

9. Mcgirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, Miller N, Williams M, Rigamonti D. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri—associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004 Oct;101(4):627-32.

P936