Involuntary psychiatric admission based on risk rather than need for treatment: report from the Dublin Involuntary Admission Study (DIAS).

Kelly BD, Curley A, Duffy RM

Department of Psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, Tallaght Hospital, Dublin, D24 NR0A, Ireland

Abstract

Aims

Involuntary psychiatric admission in Ireland is based on the presence of mental disorder plus serious risk to self/others and/or need for treatment. This study aimed to examine differences between use of risk and treatment criteria, about which very little is known.

Methods

We studied 2,940 admissions, of which 423 (14.4%) were involuntary, at three adult psychiatry units covering a population of 552,019 people in Dublin, Ireland.

Results

Involuntary patients were more likely than voluntary patients to be male, unmarried and have schizophrenia or a related disorder. Involuntary admission based on the ‘risk criterion’ (rather than the ‘treatment criterion’ or both) was associated with a shorter period as an involuntary patient for patients with diagnoses other than schizophrenia.

Conclusion

If inpatient units are intended as treatment centres rather than risk management units, the balance between considerations of risk and treatment requires careful re-examination in the setting of involuntary psychiatric care.

Introduction

Criteria for involuntary psychiatric admission and treatment vary significantly across countries but generally involve apparent risk to self or others owing to mental disorder, a perceived need for treatment, or both1-3. For involuntary admission to occur in Ireland, the patient must have ‘mental illness, severe dementia or significant intellectual disability’ and fulfil a ‘risk criterion’, a ‘treatment criterion’ or both. ‘Mental illness’ is defined as ‘a state of mind of a person which affects the person’s thinking, perceiving, emotion or judgment and which seriously impairs the mental function of the person to the extent that he or she requires care or medical treatment in his or her own interest or in the interest of other persons’ (Mental Health Act 2001, Section 3(2)).

‘Mental disorder’ is ‘mental illness, severe dementia or significant intellectual disability where’ either ‘(a) because of the illness, disability or dementia, there is a serious likelihood of the person concerned causing immediate and serious harm to himself or herself or to other persons’ (the ‘risk criterion’) or ‘(b) (i) because of the severity of the illness, disability or dementia, the judgment of the person concerned is so impaired that failure to admit the person to an approved centre would be likely to lead to a serious deterioration in his or her condition or would prevent the administration of appropriate treatment that could be given only by such admission, and (ii) the reception, detention and treatment of the person concerned in an approved centre would be likely to benefit or alleviate the condition of that person to a material extent’ (the ‘treatment criterion’) (Section 3(1)).

A person cannot be involuntarily admitted ‘by reason only of the fact that the person (a) is suffering from a personality disorder, (b) is socially deviant, or (c) is addicted to drugs or intoxicants’ (Section 8(2)). The involuntary admission order lasts for 21 days but the consultant psychiatrist can ‘revoke’ the order earlier, as soon as the patient no longer fulfils the criteria. After an ‘admission order’ or ‘renewal order’ is completed, it is reviewed by a mental health tribunal within 21 days (if it has not already been revoked by the psychiatrist, in which case an elective tribunal can be scheduled if the patient so requests). Each tribunal comprises three members: a psychiatrist, a solicitor or barrister, and a layperson. If the tribunal is satisfied that appropriate procedure was followed and the patient still has ‘mental disorder’, the tribunal affirms the order. If the tribunal is not so satisfied, it revokes the order and directs that the patient be discharged, although the patient can remain as a voluntary patient if they wish.

Ireland’s rate of involuntary admission is relatively low, at 46.7 per 100,000 population per year4. The rate in England (120) is more than double the Irish rate5. Ireland’s low rate might be a reaction to the large asylums of Ireland’s past or, more speculatively, relate to the lack of media concern about public safety in Ireland compared to England, or, possibly, generally lower levels of care in Ireland.

Legal criteria significantly shape practice: there is evidence that use of risk or dangerousness as a mandatory criterion for involuntary admission may delay initial treatment of schizophrenia6; i.e. that in countries where both risk and clinical criteria are mandatory for involuntary care, treatment is delayed. This has been described as inherently discriminatory and an unreasonable barrier to care in severe illness7,8.

To compound matters, there is evidence that legal criteria for involuntary admission tend to be interpreted paternalistically9 and recorded poorly,10 possibly because such legal terminology can be inherently ambiguous11. These are important issues: US research indicates that measures of preadmission dangerousness, rather than disability or impairment, account for most of the variance in admission status12. Dutch data confirm that police referral is the strongest independent predictor of involuntary status13.

Despite these findings, remarkably little is known about the differences, if any, between risk-based and treatment-based involuntary admissions in terms of outcomes, such as length of stay. It is known that involuntary patients with suicidal ideation have a longer length of stay in emergency departments, compared to those not seen as being at risk of suicide14. One Finnish study found that length of stay for patients involuntarily admitted on the basis of being harmful to others were longer than that for other involuntary patients (69 days versus 46 days, p=0.003)15,16, but remarkably little has been written about this topic since then. As a result, it remains unclear what, if any, are the implications of the use of risk-based as opposed to treatment-based criteria for involuntary psychiatric admission17.

Methods

We studied all admissions at three adult psychiatry inpatient treatment units in three hospitals in Dublin: Mater Misericordiae University Hospital (January 1st 2008 to December 31st 2015); Tallaght Hospital (January 1st 2014 to June 30th 2015); and the Ashlin Centre, Beaumont Hospital (July 1st 2014 until June 30th 2015). Together, these units cover a population of 552,019 people and form part of the Dublin Involuntary Admission Study (DIAS)17,18,19. Following ethical approval, we recorded gender, date of birth, occupation, marital status, date of admission, date of discharge, details of involuntary admission (where relevant) and clinical discharge diagnosis using ICD-1020. For involuntary patients, we also calculated duration spent with involuntary status.

Table 1

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Involuntary and Voluntary Patients in 3 Dublin Hospitals

Results

There were 2,940 admissions to the three units during the periods studied, of which 423 (14.4%) were involuntary. Involuntary patients were more likely than voluntary patients to be male (62.2% versus 47.2%; Chi Square 32.321, p<0.001), unmarried (80.6% versus 69.5%; Chi Square 26.824, p<0.001) and have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a related disorder (e.g. delusional disorder) (58.6% versus 20.1%; Chi Square 313.183, p<0.001). Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis among involuntary patients (58.6%); the others were affective disorders (27.2%), neuroses (2.8%), organic mental disorders (1.2%) and others (10.1%). There was no significant difference between involuntary and voluntary patients in terms of unemployment (67.2%). There were no statistically significant differences in these findings across the three hospitals, with just minor fluctuations attributable to the lower power of analyses in individual hospitals (Table 1).

Duration of admission was non-normally distributed (skewed to right) (median 12 days; interquartile range: 5-27). Median duration of admission for involuntary patients (27 days; interquartile range: 12-53) was greater than for voluntary patients (10 days; interquartile range: 4-22; Mann Whitney U: 750,651.000, p<0.001).

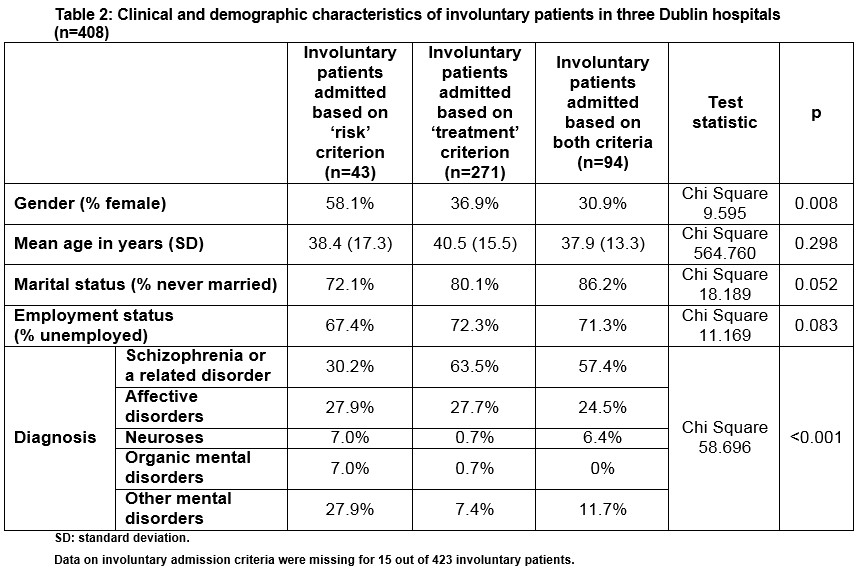

Involuntary admission based solely on the ‘risk’ criterion was associated with female gender and having a diagnosis other than schizophrenia (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in these findings across the three hospitals, with just minor fluctuations attributable to the lower power of analyses in individual hospitals (Table 3).

Table 3

Clinical and demographic characteristics of involuntary patients (n=408) in three Dublin hospitals (by hospital)

For involuntary patients, there was no statistically significant difference in overall duration of admission between patients whose involuntary admission was based solely on the ‘risk criterion’ (median 15 days; interquartile range: 5-61), ‘treatment criterion’ (median 30 days; interquartile range: 14-51) or both (median 25 days; interquartile range: 10.75-58.25; Kruskal-Wallis: 4.517, p=0.104).

For involuntary patients, time spent with involuntary status was non-normally distributed (skewed to right) (median 18 days; interquartile range: 9.25-36). Patients whose involuntary admission was based solely on the ‘risk criterion’ spent shorter durations with involuntary status (median 8 days; interquartile range: 1-20) compared to those based solely on the ‘treatment criterion’ (19 days; interquartile range: 11-37.25) and those based on both (19 days; interquartile range: 9-39; Kruskal-Wallis: 19.328, p<0.001).

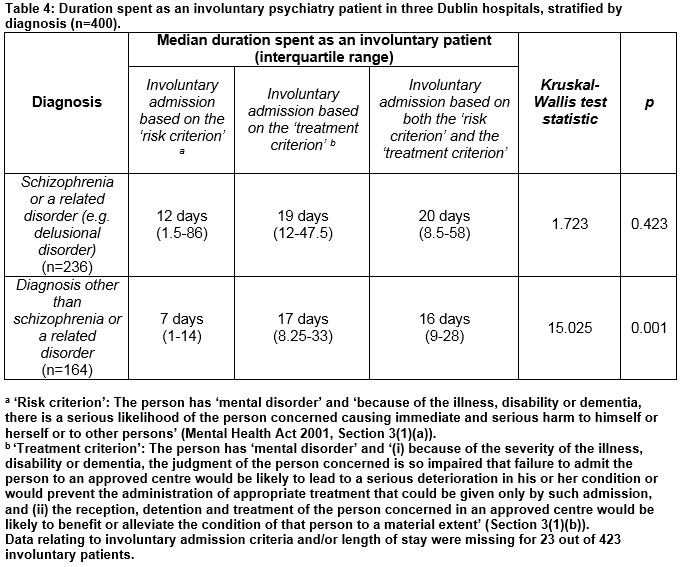

When we stratified involuntary patients by the presence or absence of schizophrenia, we found that the effect of involuntary admission criteria on time spent with involuntary status was statistically significant only for those without a diagnosis of schizophrenia (p=0.001) and not for those with that diagnosis (Table 4); i.e. use of the ‘risk criterion’ was associated with a shorter period spent as an involuntary patient only for patients with a diagnosis other than schizophrenia or a related disorder.

Following revocation of an involuntary admission order, 33.3% of patients chose to leave hospital on the day of revocation; this did not differ significantly across different criteria for involuntary care (Chi Square 150.949; p=0.759) or across hospitals (Chi Square 179.252; p=0.197). For those who chose to stay as voluntary inpatients following revocation, median duration of stay from that point onward was 9 days (interquartile range: 3-21); this did not differ significantly across different criteria for involuntary care (Kruskal-Wallis: 0.105, p=0.949) or across hospitals (Kruskal-Wallis: 1.902, p=0.386).

Discussion

We found that involuntary patients are more likely than voluntary patients to be male, unmarried and have schizophrenia or a related disorder; this is consistent with much of the literature13,18,19. We also found that involuntary admission based on the ‘risk criterion’ (rather than the ‘treatment criterion’ or both) is associated with a shorter period as an involuntary patient for patients with diagnoses other than schizophrenia. This study has several strengths: we addressed an important issue (involuntary admission); used ICD-10 diagnoses20; and included a large number of admissions (2,940, of which 423 were involuntary).

Limitations include the fact that the study relied upon the accuracy and quality of the data in patients’ files and related documentation. We studied only one diagnosis per patient although there may have been significant co-morbidity in some. Our study was conducted in three independently functioning hospitals, each with a different computer system and different ‘hard-copy’ records. As a result, not all variables of interest were collectable (e.g. country of origin, ethnicity, insight, deprivation). The role of clinical variables is especially difficult to study in a retrospective analysis such as this, as is the extent to which patients perceive coercion (even when care is ‘voluntary’). Prospective research is needed, with an emphasis on incorporating clinical variables and patients’ own experiences.

Our finding that risk-based involuntary admission is not associated with longer length of stay contrasts with findings from Finland, where length of stay for patients involuntarily admitted on the basis of being harmful to others was longer than that for other involuntary patients (69 days versus 46 days)15. This difference may be due to legal or service-related differences between Finland and Ireland; it is also notable that lengths of stay in Finland were much longer than those in Ireland (our median length of stay for involuntary patients was 27 days).

We also report the novel finding that involuntary admission based on the ‘risk criterion’ (rather than the ‘treatment criterion’ or both) is associated with a shorter period as an involuntary patient for patients with diagnoses other than schizophrenia and not for patients with schizophrenia. It is possible that patients with personality and adjustment disorders are detained under risk criteria but cannot be detained further once the acute risk subsides; this possibility merits further study.

It is also possible that some involuntary admissions in schizophrenia are initially based on risk but are continued on the basis of need for treatment. Nevertheless, if inpatient psychiatric services are intended primarily as treatment centres rather than risk management units, these findings raise an important issue about the basis of certain involuntary admissions, suggesting that the balance between considerations of risk and considerations of treatment requires careful re-examination in the setting of involuntary psychiatric care.

Acknowledgements: The authors are very grateful to the data collectors for this study and to the peer-reviewer for their comments and suggestions.

Declaration of interest:

None to declare.

Correspondence:

Brendan D. Kelly, Department of Psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, Tallaght Hospital, Dublin, D24 NR0A, Ireland

Telephone + 353 1 896 3799

Email [email protected]

References

1 Fiorillo A, De Rosa C, Del Vecchio V, Jurjanz L, Schnall K, Onchev G, Alexiev S, Raboch J, Kalisova L, Mastrogianni A, Georgiadou E, Solomon Z, Dembinskas A, Raskauskas V, Nawka P, Nawka A, Kiejna A, Hadrys T, Torres-Gonzales F, Mayoral F, Björkdahl A, Kjellin L, Priebe S, Maj M, Kallert T. How to improve clinical practice on involuntary hospital admissions of psychiatric patients: suggestions from the EUNOMIA study. European Psychiatry 26(4); 201-7.

2 Lamanna D, Ninkovic D, Vijayaratnam V, Balderson K, Spivak H, Brook S, Robertson D. Aggression in psychiatric hospitalizations: a qualitative study of patient and provider perspectives. Journal of Mental Health 2016; 25(6): 536-42.

3 Wyder M, Bland R, Crompton D. The importance of safety, agency and control during involuntary mental health admissions. Journal of Mental Health 2016; 25(4); 338-42.

4 Daly A, Craig S. Activities of Irish Psychiatric Units and Hospitals 2015 Main Findings. Dublin: Health Research Board, 2016.

5 Health and Social Care Information Centre. Inpatients Formally Detained in Hospitals Under the Mental Health Act 1983, and Patients Subject to Supervised Community Treatment: Uses of the Mental Health Act: Annual Statistics, 2015/16. Leeds: National Health Service/ Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2016.

6 Large MM, Nielssen O, Ryan CJ, Hayes R. Mental health laws that require dangerousness for involuntary admission may delay the initial treatment of schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2008; 43(3): 251-6.

7 Large MM, Ryan CJ, Nielssen OB, Hayes RA. The danger of dangerousness: why we must remove the dangerousness criterion from our mental health acts. Journal of Medical Ethics 2008; 34 (12): 877-81.

8 Large MM, Nielssen OB, Lackersteen SM. Did the introduction of ‘dangerousness’ and ‘risk of harm’ criteria in mental health laws increase the incidence of suicide in the United States of America? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2009; 44(8): 614-21.

9 Feiring E, Ugstad KN. Interpretations of legal criteria for involuntary psychiatric admission: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research 2014; 14: 500.

10 Brayley J, Alston A, Rogers K. Legal criteria for involuntary mental health admission: clinician performance in recording grounds for decision. Medical Journal of Australia 2015; 203(8): 334e1-334e5.

11 King R, Robinson J. Obligatory dangerousness criteria in the involuntary commitment and treatment provisions of Australian mental health legislation. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 2011; 34: 64-70.

12 Pokorny L, Shull RD, Nicholson RA. Dangerousness and disability as predictors of psychiatric patients’ legal status. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 17(3): 253-67.

13 Van der Post L, Visch I, Mulder C, Schoevers R, Dekker J, Beekman A. Factors associated with higher risk of emergency compulsory admission for immigrants: a report from the ASAP study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2012; 58(4): 374-80.

14 Wilson MP, Brennan JJ, Modesti L, Deen J, Anderson L, Vilke GM, Castillo EM. Lengths of stay for involuntarily held psychiatric patients in the ED are affected by both patient characteristics and medication use. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2015; 33(4): 527-30.

15 Tuohimäki C, Kaltiala-Heino R, Korkeila J, Tuori T, Lehtinen V, Joukamaa M. The use of harmful to others-criterion for involuntary treatment in Finland. European Journal of Health Law 2003; 10(2): 183-99.

16 Tuohimäki C, Kaltiala-Heino R, Korkeila J, Tuori T, Lehtinen V, Joukamaa M. Deprivation of liberty in Finnish psychiatric inpatients. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 2004; 27(2): 193-205.

17 Ng XT, Kelly BD. Voluntary and involuntary care: Three-year study of demographic and diagnostic admission statistics at an inner-city adult psychiatry unit. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 2012; 35(4): 317-26.

18 Kelly BD, Emechebe A, Anamdi C, Duffy R, Murphy N, Rock C. Custody, care and country of origin: demographc and diagnostic admission statistics at an inner-city adult psychiatry unit. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 2015; 38: 1-7.

19 Curley A, Agada E, Emechebe A, Anamdi C, Ng XT, Duffy R, Kelly BD. Exploring and explaining involuntary care: the relationship between psychiatric admission status, gender and other demographic and clinical variables. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 2016; 47: 53-9.

20 World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 10th edn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

(P736)