Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis: An Evaluation of Real World Utilisation and Expenditure in the Irish Healthcare Setting

Corcoran A1, Hickey N1, Barry M1, 2, Usher C1, 2, McCullagh LM1, 2

1Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

2National Centre For Pharmacoeconomics, St. James’s Hospital, Dublin

Abstract

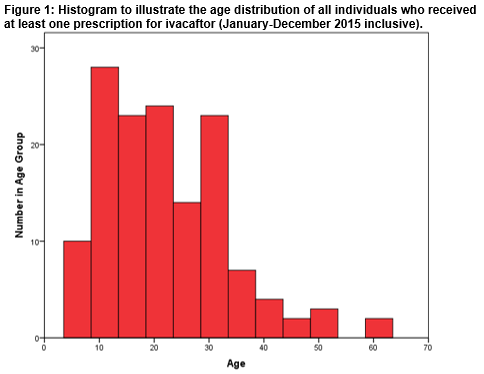

In Ireland, Ivacaftor is reimbursed, on the High-Tech Drug Scheme, for the treatment of cystic fibrosis in patients age 6 years and older who have the G551D mutation. The aim of this study was to analyse the utilisation and expenditure of Ivacaftor on this scheme in the 12 month period post-reimbursement. All patients who had received Ivacaftor (regardless of General Medical Services Scheme eligibility/ineligibility) were included. A total of 140 individuals (male=74; 53%) received Ivacaftor over the defined 12 month study period (from January 2015 to December 2015 inclusive). The cohort ranged in age from 6 years to 61 years. The mean age was 22 years; a positive skew in age distribution indicated that a greater number of the cohort were in the younger age groups. No statistically significant difference was detected in the mean ages of the male and female subgroups. Drug acquisition expenditure by the Health Services Executive on Ivacaftor over the 12 month study period was €29.81 million.

Introduction

Ireland has the highest incidence of cystic fibrosis (CF) in the world1. In 2015, 1,219 people were in the CF Registry of Ireland; 558 children and 661 adults2. CF is an autosomal recessive life-shortening disorder. The underlying cause is a mutation in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, resulting in defective CFTR protein. CFTR protein acts as a channel for the movement of chloride ions in and out of cells, which is important for the salt and water balance on epithelial surfaces3. In CF, defective regulation of salt and water absorption and secretion leads to abnormally thick secretions which continually damage many organs. CF affects multiple systems including the lungs pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, liver, reproductive and sweat glands4. Ivacaftor (Kalydeco®; Vertex Pharmaceuticals), is the first in a new class of drugs known as CFTR potentiators. CFTR potentiators are designed to increase the time that activated CFTR channels at the cell surface remain open thereby increasing chloride ion transport. This drug is orally administered5.

In Ireland, the National Centre for Pharmacoconomics (NCPE) evaluates the clinical and cost effectiveness and likely budget impact of all new drugs for which reimbursement by the health payer (the Health Services Executive (HSE)) is sought. In 2012, Vertex Pharmaceuticals (herein the ‘applicant’) submitted a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Dossier, to the NCPE, on Ivacaftor for the treatment of CF in patients age 6 years and older who have the G551D mutation in the CFTR gene. In their submission, the applicant estimatedthat the number of individuals who would be eligible for ivacaftor would increase from 121 in 2013 to 125 in 2017. On evaluation, the NCPE concluded that Ivacaftor could not be recommended at the submitted price. Subsequent price negotiations between the HSE-Corporate Pharmaceutical Unit and the applicant led to the HSE Drugs Group making a positive reimbursement decision for this indication in 20136. As such, the drug became reimbursed for this indication. In 2015, the applicant submitted a dossier on Ivacaftor for the treatment of children with CF aged 2 years and older (and weighing less than 25 kg) who have one of the following gating (class III) mutations in the CFTR gene: G551D, G1244E, G1349D, G178R, G551S, S1251N, S1255P, S549N, or S549R. The NCPE concluded that cost effectiveness had not been demonstrated; reimbursement was not recommended at the submitted price7. The NCPE is currently evaluating the cost effectiveness of Ivacaftor for the treatment of patients with CF aged 18 years and older who have the R117H mutation in the CFTR gene8.

Ivacaftor is reimbursed on the HSE-Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS) High-Tech Drug Scheme (HTDS). The HTDS was introduced in November 1996 to facilitate the supply of certain high-cost medicines by community pharmacies. Patients registered on the HTDS can apply for the General Medical Services Scheme, the Drug Payment Scheme or the other community drug schemes depending on their eligibility. The HTDS database records information on prescriptions dispensed on the scheme along with anonymised basic patient demographic information, but no outcome data. Within the database, drugs are coded using the WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. In recent times, this database has been made available to the NCPE. The objective of this study was to analyse the HTDS pharmacy claims database over a 12-month period (from January 2015 to December 2015 inclusive) to examine the number of individuals who had been prescribed Ivacaftor and the HSE expenditure. A further aim was to determine the basic demographics of the cohort of individuals who had received Ivacaftor.

Methods

A retrospective analysis (January 2015-December 2015 inclusive) of the HTDS pharmacy claims database of dispensed Ivacaftor (ATC code R07AX02) identified the study population. All patients who had received Ivacaftor (regardless of General Medical Services Scheme eligibility/ineligibility) were included. The total number of individuals who had received at least one prescription for Ivacaftor over the study period was determined. The gender and age distribution of the cohort were evaluated. The minimum and maximum ages, along with the mean age (±standard deviation) of the cohort were established. The Shapiro-Wilk test determined if the age distribution of the entire cohort was normally distributed. Skewness of the age distribution dataset was investigated. The total cohort was disaggregated by gender. The age distributions of both the male and female subgroups were investigated. The mean ages across subgroups were compared using an Independent Samples Test deemed appropriate by normality testing. The cumulative drug acquisition expenditure by the Health Services Executive on Ivacaftor over the 12-month study period was calculated. All analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel® 2013 and IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 24.0. Specific ethical approval for this study was not required as all data were fully anonymised.

Results

A total of 140 individuals (male=74; 53%) received at least one prescription of Ivacaftor over the defined 12-month study period. Figure 1 illustrates the age distribution of the entire cohort. The minimum and maximum ages were 6 years and 61 years respectively. The mean age of the cohort was 22 (± 11) years. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality indicated that the distribution of ages within the entire cohort was not normal; p<0.001. The age distribution dataset was positively skewed; Skewness =0.986.

The age distribution of the cohort was disaggregated by gender. The mean ages of the male and female subgroups were 20 (±9) years and 24 (±12) years respectively. Respective median values were 19 years and 22 years. The age distribution in the entire cohort was not normally distributed, therefore the nonparametric Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U Test was utilised to compare mean ages across the gender subgroups. No significant difference was detected in the mean ages across the subgroups; p=0.069. The cumulative drug acquisition expenditure on Ivacaftor over the 12-month study period was €29.81 million.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates that, in Ireland, a total of 140 patients received Ivacaftor from January 2015 to December 2015 inclusive. We note that this total number of patients exceeds the estimate used in the applicant’s HTA Dossier (which was submitted to the NCPE in 2012) on Ivacaftor for the treatment of CF in patients age 6 years and older who have the G551D mutation6. It was this estimate that was considered during both the NCPE evaluation process and the reimbursement decision making process for that specific indication.

The age distribution in the entire cohort was investigated. The minimum age in our cohort was 6 years in accordance with the indication for which the drug is currently reimbursed in Ireland. The mean age of the entire cohort was 22 years. A positive skew indicates that a greater number of the cohort were in the younger age groups. This is consistent with demography data gathered on individuals with CF in Ireland by the CF Registry of Ireland. No statistically significant differences were detected in the mean ages of the male (20 (±9) years) and female (24 (±12) years) subgroups. The mean, as a measure of central location, is susceptible to skew; the median is not as strongly influenced by skew. We have thus also calculated the median age of our cohort. Further, this allows comparison with the median age reported in the CF Registry of Ireland dataset. The CF Registry of Ireland (2015) reports a higher median age in males (20 years) compared to females (18 years)2. In our cohort, median ages were 19 years (males) and 22 years (females). We note that our cohort will not be representative of the entire CF population in Ireland owing to a relatively small sample size and our inclusion only of those patients who have received Ivacaftor. A literature search has not revealed any real world Ivacaftor utilisation data from other jurisdictions with which to compare our cohort. Drug acquisition expenditure on Ivacaftor, by the HSE, over our 12-month study period was €29.81 million. This was the third highest spend on a drug on the HTDS that year and represented 6.3% of total drug expenditure on the scheme over that time period9. Results from our study indicate how real world drug utilization can differ from pre-reimbursement estimates and highlights the benefit that this real world information could bring to the decision making process, particularly in relation to monitoring affordability. This study compliments previous work published by this group which examined real world use of drugs for cancer in Ireland10,11.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Our analyses do not consider the duration of therapy, dosage received or compliance in the cohort. The HTDS database does not include any efficacy and safety outcomes or any indication data and thus our study makes no consideration of these. These factors limit any conclusions being drawn regarding the possible clinical, policy and practice implications of our findings. In our analysis we have considered drug acquisition cost. HSE expenditure on a HTDS drug will also include a patient care fee (€62.03 per patient per month) which is paid by the HSE to the pharmacy to cover dispensing costs12. Finally, concerns regarding the relatively small size of our cohort have previously been alluded to.

In conclusion, this analysis has highlighted that, in 2015, the number of patients who received Ivacaftor was higher than the estimate considered during the NCPE evaluation of ivacafator in 2013. The study highlights a possible role for real world information in a post reimbursement decision making process.

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to the HSE PCRS for making the HTDS database available to the NCPE.

Correspondence:

Laura McCullagh, Trinity College Dublin

Email: [email protected]

Conflict of interest:

AC, NH, MB, CU and LMcC have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

References

1. Cystic Fibrosis Ireland. CF House, 24 Lower Rathmines, Dublin 6. Available at https://www.cfireland.ie [Accessed 4 April 2017].

2. 2015 Annual Report. Cystic Fibrosis Registry of Ireland (CFRI). Woodview Houes, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4. Available at https://www.cfri.ie/docs/annual_reports/CFRI2015.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2017].

3. Ratjen F, Tullis E. Cystic Fibrosis In: Albert RK, Spiro SG, Jett JR, ed Clinical Respiratory Medicine 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Inc; 2008. p. 593-604.

4. Schluchter M, Konstan M, Drumm M, Yankaskas J, Knowles M. Classifying Severity of Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease Using Longitudinal Pulmonary Function Data. American Journal of Respiratory and Clinical Care Medicine 2006;174(7):780-786.

5. Condren M, Bradshaw M. Ivacaftor: A Novel Gene-Based Therapeutic Approach for Cystic Fibrosis. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2013;18(1):8-13.

6. Ivacaftor (Kalydeco®). Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations, National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE), Old Stone Building, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, St. James's Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland. Available at http://www.ncpe.ie/drugs/Ivacaftor-kaldeco/ [Accessed 4 April 2017].

7. Ivacaftor (Kalydeco®) for patients with CF 2 years +. Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations. National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE), Old Stone Building, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, St. James's Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland. Available at http://www.ncpe.ie/drugs/Ivacaftor-kalydeco-for-patients-with-cf-2-years/ [Accessed 5 April 2017].

8. Ivacaftor (Kalydeco®) for the treatment of CF patients with the R117H mutation. Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations. National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE), Old Stone Building, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, St. James's Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland. Available at http://www.ncpe.ie/drugs/Ivacaftor-kalydeco-for-the-treatment-of-cf-patients-with-the-r117h-mutation/ [Accessed 5 April 2017].

9. Statistical Analysis of Claims and Payments 2015. Health Service Executive Primary Care Reimbursement Service, Finglas, Dublin 11. Available at http://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/PCRS/PCRS_Publications/PCRS-statistical-analysis-of-claims-and-payments-2015.pdf [Accessed 2017 July].

10. Spillane S, McCullagh L, Barry M, Usher C. Analysis of Pharmacy Claims for High Cost Oncology Products: Abiraterone And Enzalutamide: Usage in Mcrpc in Ireland. ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria. 29 October - 2 November 2016. 2016.

11. McCullagh L, Adams R, Barry M, Schmitz S, Walsh C. Evaluation of 'Real-World' Ipilimumab Data in Ireland. Value Health 2015;18(7):A441.

12. Final Guidelines for the Inclusion of Drug Costs in Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations. National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE), Old Stone Building, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, St. James's Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland. Available at http://www.ncpe.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Final-Guidelines-for-Inclusion-of-Drug-Costs-in-Pharmacoeconomic-Evaluation-v1.16.pdf [Accessed 10 April 2017].

(P619)