Ketamine: Future Treatment For Unresponsive Depression?

M Frere, J Tepper

School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway

Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a debilitating mental health condition which accounts for a significant portion of worldwide disability. Historically, the suggested pharmacotherapy to treat MDD have been monoaminergic-acting antidepressants, such as SSRIs or SNRIs. These drugs can provide relief, but often take weeks to noticeably improve depressive symptoms and are not always effective, leading to a condition known as Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD). It is believed that 50% MDD sufferers in Ireland suffer from TRD, and thus the development of improved pharmacotherapies is necessary. One emerging therapy is low dose, intravenous (R-S)-Ketamine (ketamine). While the molecular basis of ketamine’s therapeutic effect has not been fully determined, it has shown to effectively and swiftly mitigate the symptoms of TRD. Barriers do exist preventing the legal prescription of ketamine, including its questionable safety profile and risk of inducing dependence. Despite this, ketamine remains a promising pharmacotherapy for TRD and further investigation is required.

Introduction

The Irish Health Service Executive reports that 300,000 citizens live with depression, including 1 in 4 women1. In Ireland, like much of the world, pharmacotherapy for depression has traditionally relied on the administration of monoaminergic-acting antidepressants, including SSRIs, SNRIs, MAOIs, and TCAs. Recently, research has come to light demonstrating that the drug (R-S)-Ketamine (ketamine) —a dissociative anaesthetic—acts quickly to provide relief for sufferers of clinical depression, including many who otherwise do not see an abatement in their symptoms secondary to traditional treatment regimes.

Current Treatment for Depression

Monoaminergic-acting antidepressants have been prescribed since the 1950s and rely on the monoamine hypothesis, which states that Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is due to an imbalance in monoamines, specifically serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. The Preferred Drugs Management Programme for the treatment of depression in Ireland endorses the prescription of citalopram (SSRI) and venlafaxine (SNRI) to treat MDD, and while the monoaminergic-acting antidepressants have historically provided therapeutic relief, they do have major limitations. Namely, these antidepressants can take weeks or months for clinical improvement to be realized, and are believed to only have a 50% efficacy2. As such, many patients receive little to no relief from traditional antidepressant medication, and among those who do see a remission of their symptoms, reduced efficacy occurs over time. This leaves up to 50% of MDD sufferers whom suffer from what is known as Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD), or depression that is unresponsive to current treatment regimes2.

Depressed patients who fail to remit experience significant physical, emotional, and economic hardships. The Irish economic cost of depression is reported at €3 billion per year, the majority (66.7%) is due workplace absenteeism, a decrease in worker productivity, and unemployment3. Health and social care account for 23.4% of economic cost; 450,000 Irish citizens attend their general practitioners for mental health problems per year3. Of those mental health consultations, many are regarding patients experiencing depressive-like symptoms. This pattern extends beyond Ireland, with the WHO listing depression as the most common disability worldwide. Due to the public health nature of MDD, improving patient response to therapy remains a priority.

A variety of treatment regimens have been outlined for the management of TRD, such as augmenting the dosage of a patient’s current medication, switching medication within drug classes, or cycling between classes of antidepressant medication. Other, non-pharmacological attempts to alleviate TRD’s effects have been explored, such as vagus nerve stimulation and transcranial magnetic stimulation, and have been met with mixed success4. Despite these efforts, many sufferers of TRD experience little relief.

Ketamine as an Antidepressant

Ketamine is a non-competitive, glutaminergic NDMAR (N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor) antagonist. It was first synthesized in the early 1960s and developed for use as a safer alternative to the popular dissociative anesthetic, phencyclidine (PCP). Since the 1970s, however, due to concerns regarding its abusive nature and psychotomimetic side-effects, it been largely resigned to use as a veterinary anesthetic.

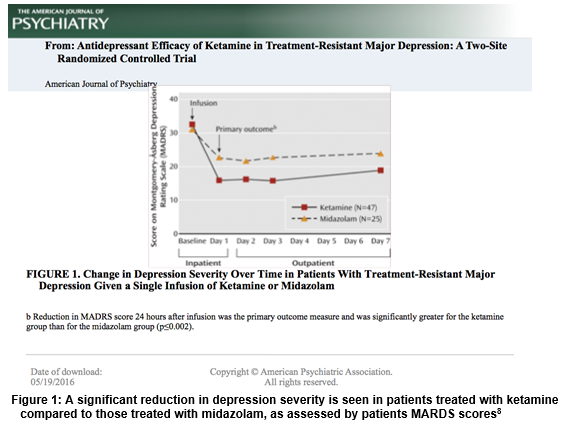

Currently, ketamine is rebranding itself within the medical community as a next-generation alternative to current antidepressant medication. Ketamine exhibits swift, potent antidepressant effects when administered to sufferers of TRD at sub-anesthetic doses and has been found to improve core depressive symptoms including suicidal thoughts, anhedonia, and depressed mood5. One clinical trial found that these potent antidepressive effects manifested within 40 minutes of a single dose of intravenous ketamine relative to placebo6. In another clinical trial, a single dose of ketamine yielded significant antidepressant effects that were found to last greater than 1 week following IV administration7. Further, a double-blind study found that 64% of patients with TRD found relief from their depressive symptoms within 24 hours of ketamine administration, compared to those treated with the benzodiazepine Midazolam, as assessed by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)8 (Figure 1) . This evidence, along with an increasing volume of literature implicates ketamine as a potential treatment option for sufferers of TRD.

Limitations to Ketamine Use

Despite the emerging research indicating ketamine as a viable, exciting treatment option for sufferers of unresponsive depression, a number of barriers remain preventing the therapeutic use of ketamine in Ireland - namely its’ safety profile and propensity to induce dependence.

Ketamine has been implicated with a number of short-term and long-term side-effects. Short-term effects include dissociative symptoms, drowsiness, confusion, elevations in blood pressure, and pulse. However, these symptoms generally resolve within 2 hours of administration9. Long-term adverse effects include kidney dysfunction, ulcerative cystitis, bladder carcinoma, and memory loss10. The evidence for these effects in chronic ketamine use is well established, however, they were observed in habitual drug users and confounding variables were often not controlled for. In addition, the majority of research currently being conducted on ketamine as an antidepressant examines only the short-term effects of ketamine on depression, so any long-term deleterious side-effects that may manifest have not been investigated. Therefore, it is difficult to relate these side-effects to low dose, short-term ketamine therapy which is currently being investigated10. The ambiguity regarding ketamine’s safety profile indicates more research is necessary before it can be authorized for depression treatment.

In addition, the potential for misuse and dependence may present a reason to limit ketamine therapy. Ketamine misuse data is outdated in Ireland, but in the past very few cases of recreational ketamine use have been reported, with only 25-35 cases between 2004 and 20059. For those who abuse ketamine, there is a risk of developing dependence, for example, 5 individuals in Ireland sought rehabilitation for ketamine dependence in 201311. One important caveat is that ketamine addiction has been reported only secondary to repeated high doses, which suggests low-dose of ketamine therapy prescribed to relieve depression is unlikely to induce dependence9. Historically, ketamine has not been a commonly abused substance and the risk of ketamine misuse is low, this leads many to believe it has the potential to be used safely as medication for long periods of time.

Due to ketamine’s questionable safety profile and potential to induce dependence, Ireland has categorized it as a Schedule 3 controlled drug, according to The Misuse of Drugs Act and the Criminal Justice Act. This means the Irish government considers ketamine abuse likely, but recognizes its therapeutic role and allows for ketamine’s legitimate use when prescribed by healthcare professionals. These Acts, combined with guidelines put forth by the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland establish a blueprint enabling safe custody, prescription and record keeping for ketamine.

Conclusion

The prospect of prescribing ketamine or a metabolic derivative to treat depression is tantalizing, but we must not jump ahead of ourselves. Many questions still remain regarding how ketamine is best administered, what dosage is ideal to treat depression, how viable is it as a long-term solution to TRD, and how it can be safely be regulated by the Irish government. In addition, the molecular basis of ketamine’s therapeutic effects is not fully elucidated. Initially, it was speculated that ketamine’s ability to augment and antagonize glutamate neurotransmission was the basis of its’ antidepressive effects, but research has since indicated that drugs which only act as NMDAR non-competitive antagonists show no significant improvement in depressive symptoms12. Thus, ketamine’s ability to decrease depressive symptoms lies outside of its ability to affect glutaminergic neurotransmission. With all of the caveats and gaps in knowledge regarding ketamine acknowledged, ketamine remains a promising solution to TRD and further investigation is advocated.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correspondence

Margaret Frere, School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Depression [Internet]. Ireland: Health Service Executive; [cited 2016 May 12]. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/az/D/Depression/ .

2. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012 Jan 1;6:369-88.

3. IMO Position Paper on Mental Health Services. Ireland: Irish Medical Organization. 2010; [cited 2016 May 12]. Available from: https://www.imo.ie/policy-international-affair/documents/policy-archive/IMOPP-Mental_Health_-Services.pdf .

4. Bewernick B, Schlaepfer TE. Update on Neuromodulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. F1000Research. 2015 Dec 2;4.

5. Lally N, Nugent AC, Luckenbaugh DA, Ameli R, Roiser JP, Zarate CA. Anti-anhedonic effect of ketamine and its neural correlates in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Translational psychiatry. 2014 Oct 1;4(10):e469.

6. Diazgranados N, Ibrahim L, Brutsche NE, Newberg A, Kronstein P, Khalife S, Kammerer WA, Quezado Z, Luckenbaugh DA, Salvadore G, Machado-Vieira R. A randomized add-on trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2010 Aug 1;67(8):793-802.

7. Zarate CA, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006 Aug 1;63(8):856-64.

8. Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Green CE, Perez AM, Iqbal S, Pillemer S, Foulkes A, Shah A, Charney DS. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013 Oct 1.

9. Critical Review of KETAMINE. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2006; [cited 2016 May 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/4.3KetamineCritReview.pdf .

10. Hasselmann HW. Ketamine as antidepressant? Current state and future perspectives. Current neuropharmacology. 2014 Jan;12(1):57.

11. Treatment Demand: Ketamine. Portugal: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction. 2015; [cited 2016 May 12]. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/stats2015#displayTable:TDI-0047 .

12. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, Potash JB, Tohen M, Nemeroff CB. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015 Sep 25;172(10):950-66.

p453