The Experience of the Management of Eating Disorders in a Pop-up Eating Disorder Unit

CM. McHugh1, M. Harron2, A. Kilcullen1, P. O’Connor1, N. Burns1, A. Toolan1, E. O’Mahony2

1.Sligo University Hospital, The Mall, Sligo

2.Sligo Mental Health Services, St Columbas Hospital, Sligo

Abstract

Anorexia nervosa affects 0.5% of the population (90% female) with the highest mortality of any psychiatric illness, usually suicide, or cardiovascular or neurological sequelae of either malnutrition or refeeding syndrome. The latter two conditions occur in the inpatient setting, carry a high mortality and are thoroughly avoidable with careful informed clinical management.

This paper provides an overview of the service and care of these patients in a general hospital setting in Ireland.

In response to a number of acute presentations a cross discipline Pop-up Eating Disorder Unit (psychiatrist, physician, dietician, nurse) was established in Sligo University Hospital in 2014 and has experience of 20 people treated according to the MARSIPAN guideline (Management of Really Sick Inpatients with Anorexia Nervosa). They are nursed in a designated ward with continuous cardiac monitoring (in addition 2 required ICU admission), with one-to-one continuous supervision, complete bed rest, careful calorie titration (usually nasogastric) with twice daily phosphate, magnesium, calcium and potassium concentrations measured and replaced. Sabotaging behaviour witnessed includes micro-exercising, requests for windows to be opened (in order to shiver/micro exercise), food concealment, faecal/urinary loading on weighing days, heavy hair accessories, vigorous page turning/toothbrushing/use of computer keypads and animated conversations.

A cross disciplinary coordinated approach to this cohort, who often inventive in their resistance to treatment, allows safe management in a general hospital setting.

Background

Anorexia nervosa (AN) has the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric conditions at 12 times that of an age and gender matched cohort (1). Predicators of mortality include social isolation, unemployment, low BMI, admission to hospital and excessive alcohol use (2). The umbrella term Eating Disorders (ICD10, DSMV) applies to AN with body dysmorphia, bulimia with/ without purging, restrictive eating patterns but there are other groups of disorders that are not included in this category, e.g. anxiety related disordered eating, diabulimia (manipulating insulin to control weight). AN affects 0.5% of the population, and 90% are young women. (3). Many die of suicide but there is a significant mortality rate among those admitted to a general hospital with deaths from both under-feeding (malnutrition) or over-feeding (refeeding syndrome (RS)) which remains an enduring legacy (4). RS is characterised by the sudden reintroduction of nutrition with hormonal stimulation, especially insulin, which leads to intracellular movement of serum electrolytes, notably phosphate, magnesium, calcium and potassium (5). The resultant intravascular electrolyte depletion can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, seizure, cardiac arrest and death.

This high mortality rates in hospitals in the UK led to the development of the MARSIPAN guidelines (Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa) to deal with behavioural and metabolic issues involved in admission, detention, refeeding and rehabilitation (6). They recommend admission to a Specialist Eating Disorder Unit (SEDU) and this paper describes the approach of a pop-up unit in a General Hospital at Sligo University Hospital (SUH).

Since inception in 2014 the Sligo team have admitted 20 acutely ill patients. This “Pop Up” team; a Consultant Psychiatrist, Physician, Clinical Nurse Specialist in Eating Disorders (CNSED), Senior Dietician, & Ward Clinical Nurse Manager, is activated with each admission, meets twice weekly and formulates careful plans for the duration of the admission. Referrals to this team come from the CNSED, general practitioner (GP), Emergency Department (ED) or Outpatients clinic (OPD). Common presentations include collapse, ongoing chronic weight loss, non-organic GI symptoms, a fall of >10% body weight, loss of >0.5 kgs/eek, prolonged fasting, or a BMI of <15 kg/m2. Among our cohort the range of BMI is 18.2 to 11.9 kg/m2, 3 admissions due to weight loss >10% and the remaining 17 had BMIs<15 kg/m2. Our mean age is 22 years, and all but 2 patients have been female.

Admission and Hospital Stay

On presentation body weight is recorded, but in our experience the admission weight can be falsely elevated with intentional water and bowel loading and objects cached pockets. In our cohort there was a significant drop in weight on the designated ward compared to the initial weight in the Acute Assessment Unit likely to represent some degree of faecal/water loading, or heavy clothing. Our ward weighing protocol involves random unannounced weighing, on the same calibrated digital scale, with minimal clothing and patient facing away from the digital dial. Results are not disclosed to the patient to avoid excessive focus on weight. The team has experience of patients hiding batteries in sanitary towels on weighing days, weights embedded in hairstyles, and hems of clothing, and gripping of scales with toes. Sabotaging behaviour was seen in almost all of our cohort, and can be inventive so patients are nursed in the observation bay of the designated medical ward, bed-side curtains remain open except for toileting, with one-to-one supervision at all times, usually a health care assistant (HCA). Changes of personnel and shifts pose challenges. Such personnel are instructed not to engage in conversation, as this is met with animated conversation in an effort to micro-exercise. Clear handover to incoming HCAs and on-call staff is paramount and flustered interns are often requested to chart laxatives, so clear instructions for out-of-hours staff is important.

Full bed rest is enforced to minimise calorie expenditure. A commode is supplied by the bedside, but no bathroom trips are allowed, as it is a vulnerable point for sabotage. Bedding must be examined daily for feed/food hiding in the pillows or wet mattresses as nasogastric feeds were disconnected quietly. Napkins and wipes are not permitted because of the risk of concealment of food. Food can also be deposited in lockers, neighbouring patient’s tables/lockers so constant supervision guidelines are important.

A “separation period” is enforced whereby phones, computers and all electronic equipment is removed from the patient. We have experienced cases of bullying by peers on electronic devices, so removal of all such intrusive portals is important to allow this to be a “safe space” free from bullying, and also to permit “reflective time” and “recovery time” without electronic distractions. We have experienced one patient micro exercising by typing vigorously on the laptop.

We have had experience of family members colluding with the sabotaging behaviour, insisting that the problem is gastrointestinal disease, bringing in food, hiding food, and relatives sitting constantly by the bedside and interfering in neighbouring patient’s affairs. Family psychological counselling is an integral part of the longer term process but initially visiting may have to be restricted in the interest of rest, calorie preservation and mindful of other patients on the ward.

Physical stigmata of disease present on admission include emaciation, bradycardia (lowest 45 bpm), mild hypotension (lowest systolic pressure on admission was 96mmHg) and one case of visible stigmata of self-harm (scars). We have had no cases of dental or finger erosions, and one case of hypothermia (33.4C).

Admission hepatic serology has been normal with one case of a transaminitis (AST of 555 U/L (0-32)) on admission from likely from malnourishment and autodigestion (5), and this individual had a further transient rise during refeeding (AST 1126 U/L), which normalised at day 9.

One subject had a low serum blood glucose on admission (3.9mmol/L (reference range 4.0 – 7.0mmol/L). All others were within the normal range. One individual had a fall of serum blood glucose on day 4 to 3.1mmol/L with the development of an aspiration pneumonia. Hypoglycaemia can often be a clinical indicator of sepsis in this population (7). Serum albumin, haemoglobin, and leucocytes have been uniformly normal.

Feeding

The approach to initial feeding can involve profound calorie restriction at 5-10 cal/kg/day with slow augmentation to minimise electrolyte imbalances, or higher (1400kcals od) with prophylactic phosphate administration (8). Twice daily electrolytes are measured and replaced (9). Patients are at risk of Wernickes Encephalopathy and vitamin replacement can be oral, NG or intravenous. In our experience patients strongly request the oral route but debilitation and muscular weakness increase the risk of aspiration and we experienced one case of aspiration of the vitamin syrup leading to aspiration pneumonia needing ventilation, and inotropic support.

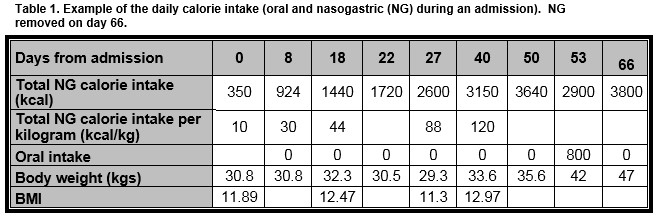

The duration of nasogastric feeding and oral supplementation is often protracted and weight gain slow and while starting low the calorie augmentation is expanded significantly and high calorie intake is often needed to achieve the end weight (table 1). Return to mobility is graded and supervised to avoid excesses.

Initial cognitive impairment precludes real psychological intervention. As BMI increases there is a slow introduction of enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy techniques (CBTE) which will start proper upon discharge.

Discharge and follow up

Discharge is preceded by a period of “day-leave” and team assessment of coping mechanisms by the larger family support unit. Discharge is followed by twice weekly follow-up cognitive behavioural therapy (enhanced) (CBTE) with the CNSED, as well as dietetic, and medical outpatients.

To date there has been 1 patient who had a voluntary readmission with a BMI of 18.3, reporting restricted eating and feeling weak but self discharged within 24 hours. There have been no deaths. Three have disengaged with the service follow up CBT-E prior to completion of the programme, and 2 of these have had a fall in BMI from discharge, and other patients have an increased BMI at last recorded weighting compared to that at discharge. Satisfaction ratings are high among service users on formal evaluation.

Conclusion

This is a very challenging cohort of patients with a significant mortality. The nature of the illness crosses community/hospital and medical/nursing/psychiatric domains and with poor insight, family collusion and sabotage these patients can struggle with multiple disparate care-givers. Hence multidisciplinary cooperation and communication is essential for successful outcomes. Collaboration, appropriate clinical skills and patience are the keys to success with this cohort of patients. Of paramount importance is physician awareness of the clinical issues that are presented by these patients and increasing awareness among health care professionals to allow early identification, appropriate management and prevention of morbidity in this patient group.

Correspondence:

Professor Cathy McHugh, Sligo University Hospital, The Mall, Sligo,

E-mail: [email protected]

References

1. Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1284-93.

2. Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, Franko D, Charatan DL, Herzog D. Predictors of mortality in eating disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 179-183;60(2).

3. Department of Health. A Vision for Change: Report of the Expert Group on Mental Health Policy. 2006.

4. Smink FRE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(406-414).

5. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-8.

6. The Royal Colleges of Psychiatrists Physicians and Pathologists. MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. 2014.

7. Mehler PS, Brown C. Anorexia nervosa – medical complications. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;3(11).

8. Leitner M, Burstein B, Agostino H. Prophylactic Phosphate Supplementation for the Inpatient Treatment of Restrictive Eating Disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(6):616-20.

9. Boland K, Solanki D, OHanlon C. Prevention and treatment of refeeding syndrome in the acute care setting. Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition & Metabolism. 2013.

P806