Trends in the Fractures and Fatalities of Farmyard Injuries in Ireland: A 10 year analysis

MJ Lee, DT Cawley, JP Ng, K Kaar

Department of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, University Hospital Galway, Newcastle Road, Galway, Ireland

Abstract

The farming and agricultural sector remains one of Ireland’s primary industries. Fatality rates remain higher than the European average. The aim of this study was to analyze the national trend in hospital in-patient admissions for farmyard related fractures and related fatalities in Ireland from 2005 to 2014. Relevant socioeconomic trends were used for comparison. There were 2,064 farm-related fractures and 187 fatalities recorded over the same period. Despite a decrease in incidence of farmyard fractures over 2005-2014, fatality rates have increased indicating the alarming continued occupational hazards and severity of sustained injuries.

Introduction

In Ireland, 66% of the land area is dedicated to agricultural production, and the agricultural industry accounts for 6% of the Irish workforce1. The agricultural sector workforce within the European Union accounts for 17.5 million persons, representing 7.7% of the total EU labour force. It is estimated that over 600 fatalities related to the agriculture and forestry sector occur each year in the EU, with an average farm fatality of 12 per 100,0002. Published official reports show that current Irish farm fatality rates remain high, with 30 recorded in 20143. In Ireland, fatalities rates associated with injury in the agricultural and farming sector remain up to eight times higher than any other Irish industry1,3.

Previous local and regional studies have documented farmyard injury presentations to emergency departments in rural Ireland. Livestock and machinery were the main sources of injury on Irish farms, with the months June, July and August recording the largest number of presentations to the Accident and Emergency Departments4,5,6. Studies in Britain and the United States had found manual handling and carrying to be the main cause of non-fatal injuries, with heavy machinery the main factor in fatal injuries7.

Awareness of this problem has been low among the farming community despite recent media attention. The EU framework directive on Occupational Health and Safety (89/391/EEC) was implemented in Ireland via the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act (1989), and a national publicity campaign has been attempting to tackle the overall incidence of injury by educating agricultural employees through a Farm Safety Code of Practice. By 2009, 40% of farmers had completed the programme8.

Although there have been published analyses of the causes of farming injuries, information on the nature and severity of the injuries is sparse. Orthopaedic trauma has been identified in around 47% of an historical Canadian study with a higher incidence in fatalities9. In addition to the association with other life-threatening injuries, fractures often result in prolonged disability, with an impact on the long-term ability to work5,7.

The aim of this paper is to critically analyse the national data for hospital admissions with fractures resulting from farmyard injuries over the last 10 years in the Republic of Ireland, and to explore the associated fracture and fatalities trends.

Methods

Data was collected and analyzed from the ‘Hospital In-Patient Enquiry’ registry (HIPE)10, which is the principal source of national data on discharges from acute hospitals in Ireland. All 54 acute public Hospitals in Ireland are included, with data taken from medical charts or records and coded by trained clinical coders before entering into HIPE system. Categories include demographic, clinical and administrative data on discharges from, and deaths in, acute public hospitals nationally. Discharges are coded using the ICD-10-AM system (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems coding scheme, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification)10. All HIPE data between 2005-2014, which included a principal diagnosis of ‘fracture, poisoning or certain other consequences of external causes on farms’ was collated. The definition included farm buildings, land under cultivation or ranches and excluded the farm house or home premises of the farm. The term “fracture” specifically relates to fractures necessitating hospital admission.

This collation was supplemented with agricultural statistics and farm fatality data from two other official government sources, in Ireland and in Europe: the Agriculture and Food Development Authority (Teagasc) survey on National Farms in Ireland11 and the Irish Health and Safety Authority Annual Reports to the European Parliament on Farming Hazards4. Fatality figures for farm injuries in Ireland were accessed directly from the Health and Safety Authority in Ireland website for annual statistics.The data was analysed using IBM SPSS statistics version 19.0. (IBM, Armonk, N.Y) with data presented to display injury trends.

Results

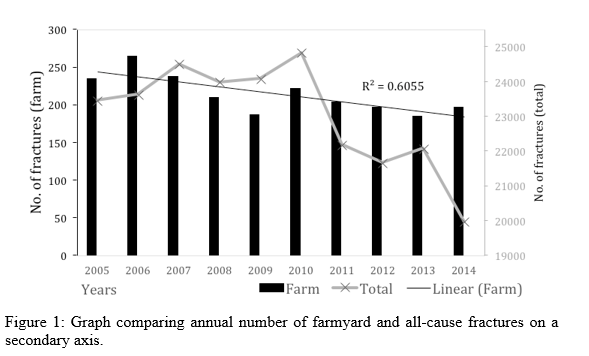

From 2005-2014 there were 2,064 farm-related fractures admitted as inpatients to Irish Hospitals, representing 0.89% of all-cause national fractures (n: 230,266)10. The number of annual farming fractures has shown an overall decline from 235 in 2005 to 197 in 2014. Both sets of data demonstrated an isolated spike in fracture incidence in 2010 with subsequent annual numbers falling to lower mean levels (Figure 1). Fractures of the wrist and hand had the highest incidence.

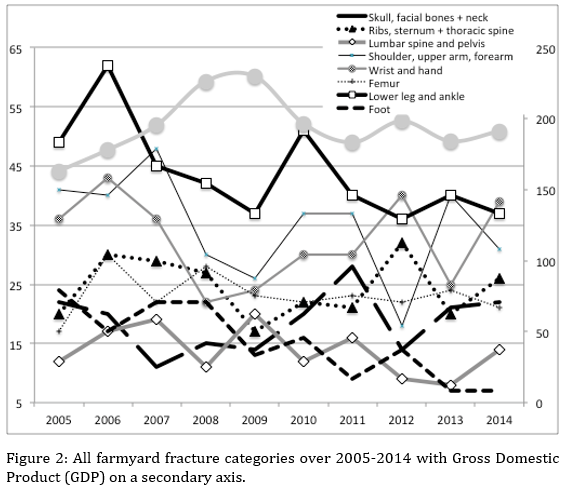

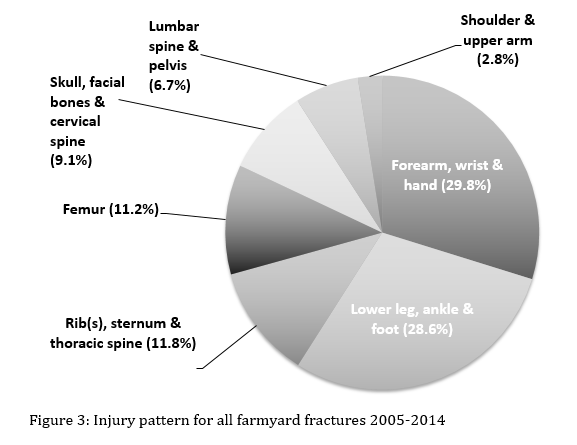

During the period of greatest economic activity (2006-2009), fractures decreased in most categories, including lower leg, arm, wrist & hand and thorax. Categories including lumbar spine and pelvis, femur, skull, facial bones and neck did not decrease overall during this time. Since 2010, economic activity has been static without any significant trends in overall fracture incidence or within categories (Figure 2). The lower leg and ankle accounted for 21.2% of total fractures. When combined, the lower limb (femur, lower leg, foot and ankle) sustained the greatest percentage of fractures 39.8% (n: 822). The combined upper limb (shoulder, upper arm, forearm, wrist and hand) was the second most commonly injured 32.6% (n: 673) and the axial skeleton (skull, facial, neck, ribs, sternum, spine and pelvis) made up 27.6% (n: 569) of those injured (Figure 3).

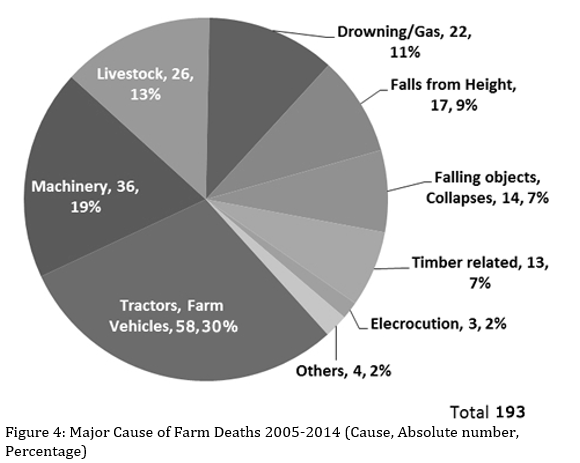

Farm fatality data demonstrated 192 farm fatalities recorded in Ireland over this period. Subanalysis of this demonstrates that farm vehicles/machinery and livestock accidents accounted for 72% of these (Figure 4). The lowest recorded total all-cause number of fatalities was in 2009 with 9 deaths, and the highest peak occurred in 2014, with 30 deaths. There was a declining trend in fatality numbers through 2005-2009, with a mean of 15.6 deaths (S.D. 4.45), with an increase from 2010 to 2014 with a mean of 22.8 per year (S.D. 5.16). 30 deaths occurred in 2014, the highest in fatality in twenty years and in that year represented 55% of all Irish work-related deaths12.

The overall number of people working in the agriculture sector declined from 109,600 in 2005, to 85,000 in 201013. The official calculated farm fatality rate increased from 15 per 100,000 workers in 1996, to 22 per 100,000 by 2009. The age profiling of farm fatalities shows elderly farm labour workers >65 years old frequently make up 40-50% of annual fatalities (2005-2007, 2011-2012), with children aged up to 17 years old varying from 10-20% each year (excluding 2011/2012) and a high of 23% in 201312.

Discussion

The study provides us with insight into the patterns of national farmyard fracture rates and associated farmyard fatality rates in Ireland. We identified an overall decreasing trend in the overall number of farmyard-related fractures from 2005-2014, representing a 21% decline over the examined period (Figure 1). National all-cause fracture numbers also declined over the same period by 14.9%. However, the total number employed in the agriculture sector reached a high in 2008, and by 2010 had fallen by 25%, only eventually recovering by 2013. Thus, the relative risk of sustaining a fracture whilst working on a farm has not declined. The lower limb remained the most commonly injured site with 39.8% of injuries during the study period, followed by the upper limb 32.6% and the axial skeleton 27.6%. Often a severe fracture such as those profiled in previous farm injury papers7 results in a prolonged recovery and absence from work. The economic consequences may be significant. In Ireland 90% of all farm injuries are suffered by farm family members, compounding the social and economic impact12. The period of most economic growth in Ireland co-incided with a decrease in most fracture categories except those indicating the most severe injuries, including skull, femur and pelvis. Ireland was affected by the economic recession since 2008-2009, particularly in rural farming communities. There was an emergence of a ‘part-time’ farmer, with supplementary employment during the week and a farm managed ‘on the side’. This activity to supplement income may have exposed workers to the recognized hazards on a farm, but without the daily familiarity of full time farming routine and accompanying safe practice.

Statistics collected from the Teagasc National Farm Survey supported these findings, showing an overall decline in total injury numbers, albeit with a spike in 20104. Teagasc findings showed the farm operator to be the most commonly injured farmyard worker (73.3%) and the farmyard being the most common location of injury (71.5%). A previous regional study in the West of Ireland identified livestock as the most common cause of non-fatal injury5. A 10 year single-centre review of cow-related injuries in Ireland demonstrated the potentially significant injuries sustained in such encounters, with high recorded Injury Severity Scores representing a substantial hazard6. With current European milk quotas due to be lifted1, the volume and intensity of dairy farming is primed to increase, with the attendant risks of injury. The most concerning finding was the increase in fatal injuries on the farm and agricultural setting. Total fatalities have increased from 2010-2014, and 2014 has been the worst year on record, with 30 deaths. A higher proportion of injuries therefore is resulting in fatal outcomes. Age is now a major contributory factor in farmyard accidents, both fatal and non-fatal. With the average age of a farmyard worker in Ireland standing at 57 years old and increasing4, a significant injury is more likely to result in a fatal outcome than the equivalent injury in a young worker. Teagasc data recorded that in 2011, more than 50% of farm fatalities occurred in those over 65, and up to 70% in those over 55.

Ireland has a farming sector that is advancing in technology and mechanization in tandem with global farming practice. Over the last 10 years, heavy machinery and tractors are the most common source of fatal injuries in Ireland, accounting for 49% of the total, which is mirrored in other European Countries14. Recently, this dominance has declined, with an increase in livestock injury as the source of fatality, particularly in the dairy sector 4. The increasing mechanization of farming practice may have served to aid a reduction in total injury, but may pose a new and evolving source of significant high-energy trauma. The increasing age of farmers combined with rapid technology advancement and mechanization is a relationship fraught with dangers and potentially fatal injuries. The industry is primarily comprised of private, self-employed farming families, making safety training and standard setting more challenging to ensure. Compliance with Health and Safety Legislation enacted in 1989 has been difficult to enforce across areas of the farming community2,3. Family members are often co-workers on the farm and surveys have found farm family members suffer over 90% of all farmyard injuries3,6. This may contribute to a lower rate of insurance claims and suspected underreporting of injuries on farmyards4,6.

HIPE data registers all data in public hospitals in Ireland but with some limitations. Private hospitals with part-time emergency departments are not included. Incorrect coding and underreporting limits the analysis. Information omitted on fracture classifications includes open soft tissue injuries, which are a significant problem on farmyards with bacterial contamination and for which specialized management is required7. With more recent advances in imaging, underlying fractures are more frequently diagnosed than previously observed15. Obtaining a statistically significant trend and relationships between demographics is not usually possible, because of differing reporting protocols. Fatality records lack the full detail of injuries sustained and mechanism of death, making direct correlation to the injury difficult.

Awareness campaigns to address this issue should therefore consider targeting farmers over 55 years old, particularly those with extensive machinery, and those with livestock11. Campaigns need to engage with the spouse and family, given the alarming fatality rates involving the family and those under 17 years of age12. This is not a new phenomenon with similar conclusions made in Great Britain over 20 years ago16. Voluntary safety courses reported attendance rates as low as 22% in 2011, showing the penetration and engagement of education campaigns remaining a challenge. For medical teams, the data analyses should increase the awareness of the complexity, fatality rates and injury severity patterns of farmyard injuries, to direct local emergency departments, and to prioritize trauma management protocols. Multimedia, exhibitions and education at annual farming calendar events may promote such awareness.

Correspondence

Matthew Lee, Department of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, University Hospital, Galway, Newcastle Road, Galway City, Ireland

Email: [email protected]

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare that no benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. No funds were received in support of this study.

References

1. O’Halloran M, Higgisson B, Griffin PJ. Irish Health and Safety Authority Report to ‘The Oireachtas Joint Committee On Agriculture, Food and Marine.’ 29 Jan 2015. http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/agriculturefoodandthemarine/Opening-Statement---Health-Safety-Authority-290115.pdf

2. Griffin, PJ. Safety and Health in Agriculture "Farming - a hazardous occupation - how to improve health & safety?" 2013. Health and Safety Authority. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201303/20130321ATT63633/20130321ATT63633EN.pdf

3. Griffin, S. Farming is still the most dangerous occupation in Ireland. Irish Independent. 2014. 02 Jan 2014. http://www.independent.ie/business/farming/rise-in-fatal-farm-accidents-looks-set-to-worsen-30305926.html

4. Meridith, D. Farm Fatalities in Ireland (1993-2014) Data Visualisation. Irish Agriculture and Food Development Authority. 2014 http://www.teagasc.ie/publications/2014/3291/Farm-Fatalities-1993-2014-Farm-Safery-Workshop-Ashtown.pdf

5. Byrne FJ, Waters PS, Waters SM, Hynes S, Thuairisg C. N, O'Sullivan, M. 2011. Demographics, nature and treatment of orthopaedic trauma injuries occurring in an agricultural context in the West of Ireland. Irish Journal of Medical Science , 180, 185-189.

6. Murphy C.G, McGuire C.M, O'Malley N, Harrington, P. 2010. Cow-related trauma: a 10-year review of injuries admitted to a single institution. Injury , 41, 548-550.

7. Angelous A, Lindner T, Vrentzos G, Papakostidis C. Prevalence and current concepts of management of farmyard injuries. 2007. Injury , 38, 26-33.

8. Teagasc- Irish Agriculture and Food Development Authority. 2015. Retrieved June 15th, 2015. www.teagasc.ie/news/2009/200908-14.asp

9. Pickett W, Hartling L, Brison R, Guernsey J. Fatal work-related farm injuries in Canada, 1991-1995. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1999;160:1843-8

10 HIQA. Retrieved June 15th, 2015 from Health Information and Quality Authority. Hospital Inpatient Enquiry. 2015. Ireland. http://www.hiqa.ie/healthcare/health-information/data-collections/online-catalogue/hospital-patient-enquiry

11 Teagasc. Retrieved June 15th, 2015 from Agriculture and Food Development Authority Annual Reports. http://www.teagasc.ie/nfs/

12 HSA. Retrieved June 15th, 2015, from Health and Safey Authority. 2014. http://www.hsa.ie/eng/Your_Industry/Agriculture_Forestry/Further_Information/Fatal_Accidents/

13. Annual Review and Outlook for Food and Agriculture 2005-2014. Ireland. Retrieved June 15th, 2015. www.agriculture.gov.ie

14. Rorat M, Thannhauser A, Jurek T. Analysis of injuries and causes of death in fatal farm-related incidents in Lower Silesia, Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015; 22: 271–274.

15. Cawley D, Hennessy A, Curtin P, Bergin D, Shannon F. 'Ready-access' CT imaging for an orthopaedic trauma clinic. Ir Med J. 2011;104:81-3.

16. Cameron D, Bishop C, Sibert JR. Farm accidents in children. BMJ. 1992 Jul 4;305:23-5

P494