Irish Medical Students’ Understanding of the Intern Year

1,2P Gouda, 1K Kitt, 3D S. Evans, 3D Goggin, 4D McGrath, 5J Last, 6M Hennessy, 7R Arnett, 8S O’Flynn, 1F Dunne, 1,3D O’Donovan

1 National University of Ireland, Galway

2 University of Alberta

3 Department of Public Health, HSE West

4 University of Limerick

5 University College Dublin

6 Trinity College Dublin

7 Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

8 University College Cork

Abstract

Upon completion of medical school in Ireland, graduates must make the transition to becoming interns. The transition into the intern year may be described as challenging as graduates assume clinical responsibilities. Historically, a survey of interns in 1996 found that 91% felt unprepared for their role. However, recent surveys in 2012 have demonstrated that this is changing with preparedness rates reaching 52%. This can be partially explained by multiple initiatives at the local and national level. Our study aimed evaluate medical student understanding of the intern year and associated factors. An online, cross-sectional survey was sent out to all Irish medical students in 2013 and included questions regarding their understanding of the intern year. Two thousand, two hundred and forty-eight students responded, with 1224 (55.4%) of students agreeing or strongly agreeing that they had a good understanding of what the intern year entails. This rose to 485 (73.7%) among senior medical students. Of junior medical students, 260 (42.8%) indicated they understood what the intern year, compared to 479 (48.7%) of intermediate medical students. Initiatives to continue improving preparedness for the intern year are essential in ensuring a smooth and less stressful transition into the medical workforce.

Introduction

The intern year in Ireland is a one-year period of pre-registration structured clinical training immediately following graduation from medical school. Upon completion, trainees are provided a certificate of experience, entitling them to automatic registration in all EU countries1. The transition from medical student to intern can be difficult, not least because interns begin to assume some clinical responsibility. Previous studies have demonstrated that this transition is made difficult by the lack of protected time for education, insufficient feedback on performance and deficiencies in the way undergraduate training prepares them for internship2,3. Irish studies undertaken in 1996, 2003, 2005 and two studies in 2012 have demonstrated that 9%, 68%, 38%, 49% and 52% of new interns felt prepared entering the intern year2-5. This increase over the years could be attributed to the establishment of Intern Training Networks and a National Intern Training Programme in 2009/2010 and changes to the undergraduate curriculum6. The most recent report on the topic demonstrated that interns felt least prepared for clinical procedures and administrative tasks, while more confident in their clinical knowledge7. One factor, which may influence perceptions of preparedness for internship, is the degree to which medical students understand what the intern year entails. Our study aimed to evaluate medical students` understanding of the intern year and the factors associated with the level of understanding after concerns were raised in an Irish national survey of interns4.

Methods

An online cross-sectional survey was distributed to all medical students studying in Ireland via an online survey tool (Survey Monkey v. March 28, 2012 http://www.surveymonkey.net) with the help of medical school administrators. A reminder email was sent out to all students two weeks later and the survey remained open for a total of four weeks. The questionnaire applied Likert scale responses to a set of statements which aimed to elicit the degree to which understanding of postgraduate training in Ireland was associated with migration intentions, respondents’ understanding of the intern year and subsequent career plans. Pearson’s Chi-square was utilised to determine the significance of differences in responses to questions. SPSS v.20 was used for data analysis. The questionnaire asked respondents to rate their agreement/disagreement to the following statement: “I understand what the intern year after graduation entails” In addition, age, gender and nationality were also obtained. Location of secondary school was used as a proxy for citizenship, as it highlights the demographics we are interested in. Ethical approval was granted by the College of Medicine Nursing and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

Results

Response rate

The survey was administered electronically to 6,180 students enrolled in a recognised medical course in one of Ireland six medical school in January 2013 of whom 2,273 (37%) responded, and 2248 responded to questions regarding their understanding of the intern year.

Participant demographics

Of those who responded 999 (44.4%) were male with 213 (9.5%) aged 18-20, 534 (23.8%) aged 21-23, and 447 (19.9%) over 23 years of age. Junior (pre-medical and first year), intermediate (second and third year) and senior (fourth and fifth year) medical students accounted for 607 (27.0%), 983 (43.7%) and 658 (29.3%) of respondents respectively. Of those who responded, 1,505 (66.9%) had completed secondary school in Ireland, 121 (5.4%) in another EU country and 622 (27.7%) in a non-EU country.

Understanding of intern year

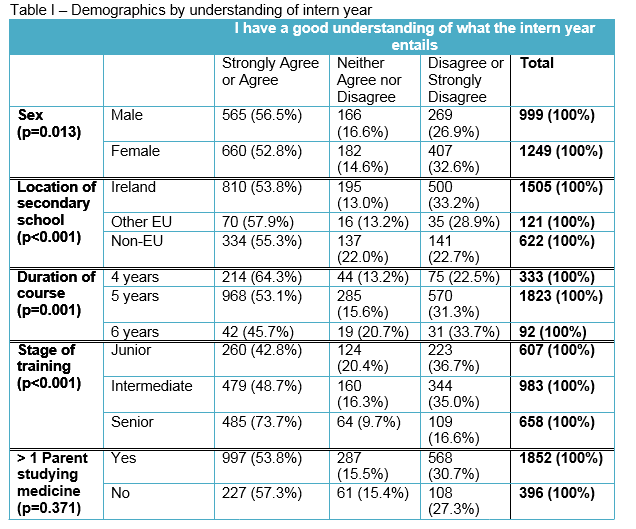

Fifty-four percent (n=2,248), of students agreed or strongly agreed that they had a good understanding of what the intern year entails, 348 (15.5%) neither agreed nor disagreed and 676 (30.1%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. There was a small difference between genders, with 565 (56.5%) of males indicating they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, compared to 660 (52.8%; p = 0.013). Students who completed secondary school outside of Ireland perceived to have a better understanding of the intern year, with only 141 (22.7%) of non-EU students indicating that they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. This is compared to 35 (28.9%) of EU students and 500 (33.2%) of Irish students (p < 0.001). There was linear relationship between duration of course and perceptions of understanding the intern year, with 42 (45.7%) of students enrolled in a six year program agreed or strongly agreed with statement, compared to 968 (53.1%) in the five year program and 214 (64.3%) in the four year program (p < 0.001). In addition, junior medical students were least likely to agree or strongly agree with the statement 260 (42.8%), compared to 479 (48.7%) of intermediate medical students and 485 (73.7%) of senior medical students (p < 0.001). There was no difference between students who had a parent who had studied medicine and those that did not.

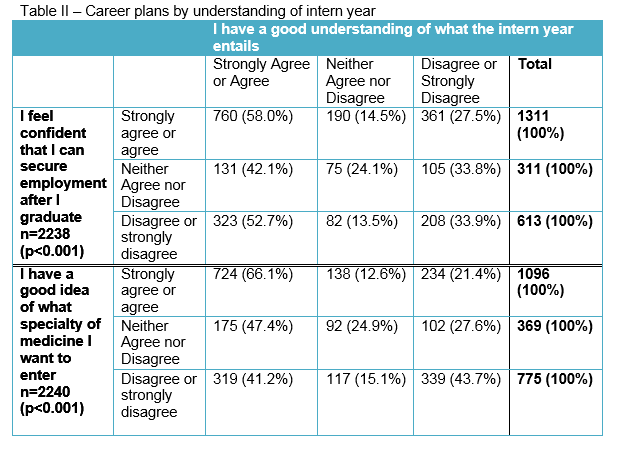

Respondents who indicated that they understood the intern year (strongly agreed or agreed with statement) often also indicated that they were confident in their ability to secure employment and had clear ideas about postgraduate specialty career choices (strongly agreed or agreed with statements) as seen in table II.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the majority (55%) of medical students perceived themselves to have a good understanding of intern year in Ireland. Understanding of the intern year was lower in the junior and intermediate years, which is likely to be related to the level of clinical exposure. Understanding appears to increase as the undergraduate course progresses, with nearly 75% of senior medical students reporting a good understanding of the intern year. This may be due to multiple initiatives at both the undergraduate and postgraduate level to ease the transition into the intern year following the recommendation by the Irish Medical Council that undergraduate curriculum should include a period of intern shadowing8; this is supported by a survey of interns that showed that 77% found a shadowing process beneficial6.

The issue of medical graduates lack of preparedness is not unique to Ireland with similar situations described among senior medical students in the UK and New Zealand9,10. Studies in the UK have demonstrated the effectiveness of initiatives at the medical school level in preparing students for postgraduate training. While only 36% of graduates from 1999 and 2000 felt their medical school had prepared them well, this increased to 58% among graduates of 200511.

However a survey of 700 medical gradautes established that despite overall rising confidence, gradautes still felt poorly prepared for prescribing and execuring some practical procedures which would be expected of them as interns12. Concerns regarding prescribing preparedness have also been identified in the Irish context13. So while medical students may percieve themselves to be prepared for the intern year, this may not be true in specific technical aspects of the role of an intern, such as perscribing skills. A study in the UK showed that junior doctors were aware or their prescribing errors, yet still remained confident in their perscribing skills14,15. Factors influencing perscribing errors and competence are multifactorial and complex and warrant early intervention in the undergraduate medical curriuculum16.

One initiative in Ireland, at the local level, to improve preparedness of new graduates for the challenges of the intern year has been the creation of a four week intern-training programme that covered clinical and technical skills as well as a four day shadowing experience. An evaluation of this programme revealed that prior to commencement, students were least prepared for technical aspects of the intern year such as medication prescribing, decision making ability and managing an emergency5. Student’s perception of being prepared rose from 43% precourse to 96% postcourse for medication prescription, 31% to 53% for decision-making ability and 12% to 26% for managing anemergency. For logistical reasons an additional four week training programme may not be feasible for all intern training programmes. The option however of more active involvement of senior medical students in clinical practice could also be considered. The approach of requiring senior medical students to assume clinical responsibility under close supervision has proven to be very effective in optimising their learning and preparedness for practice17,18.

Interestingly, our study suggests that students that had a better idea of what speciality they were interested in also perceived a better understanding of the intern year. This suggests that initiatives at the undergraduate level to increase understanding of career opportunities may also be an opportune moment to discuss training pathways, what each stage of training entails and should actively engage students in the process. In addition, we see that graduate entrants have perceived a better understanding of the intern year. This may due the significant variations in motivation and attitudes prior to enrolling in the medical degree19,20. Encouraging medical students to actively engage in career planning activities at the undergraduate stage may act as a trigger for self-directed learning, giving them a better idea of what is involved in postgraduate training.

While our study describes student perception of preparedness for the intern year in the largest survey of medical students Ireland, there are several limitations that must be taken into account. There was no correction applied in our statistical analysis for multiple comparisons so apparent associations should be analysed with caution. In addition, we describe student perceptions of preparedness, which in itself is not the same as being prepared. Future studies should aim to elicit both perception of preparedness before starting the intern year and actual preparedness shortly after beginning the intern year. While we report a 37% response rate, lower than previous studies, our study reports the largest survey of medical students in Ireland to date. However, the possibility of non-responder bias remains. The increase in survey research targeting medical students may also be responsible for survey fatigue. School administrators may need to begin to prioritise research opportunities for their students to be involved in.

The progression from medical student to internship can be stressful and can potentially be associated with medical error.21 Our study has demonstrated in a large sample of Irish medical students that understanding of the first stages of postgraduate medical training in Ireland is comparable with medical students in other jurisdictions. While self-reporting of preparedness is a potential limitation, it is accepted that perceptions of ability are predictors of behaviour and therefore it is a valid approach22.

It is inevitable that learning on the job will occur, however a key function of all the medical undergraduate curricula is ensuring optimal preparedness for practice. Although the overall majority of medical students perceive themselves to be prepared for the intern year, efforts to continue improving medical student knowledge of the intern year should be considered. These initiatives may take the form of increased intern shadowing, the development of web based material and the delegation of selected clinical responsibilities to senior medical students under appropriate supervision. Future research and intervention should involve all stakeholders including medical school, postgraduate training programs and medical students.

Correspondence: Pishoy Gouda, 46 Mcleod Crest, Leduc, Alberta, Canada, T9E6N9

+ 1 780 9864080

References:

1.Irish Medical Council. Medical Council Education Website [Internet]. medicalcouncil.ie. [cited 2014 Nov 5]. Available from: http://www.medicalcouncil.ie/Education/

2.Hannon FB. A national medical education needs’ assessment of interns and the development of an intern education and training programme. Med Educ. Wiley Online Library; 2000;34:275–84.

3.Finucane P, O’Dowd T. Working and training as an intern: a national survey of Irish interns. Med Teach. 2005 Jan;27:107–13.

4.Abuhusain H, Chotirmall SH, Hamid N, O'Neill SJ. Prepared for internship? Ir Med J. 2009 Mar;102:82–

5.Byrne D, O'Connor P, Lydon S, Kerin MJ. Preparing new doctors for clinical practice: an evaluation of pre-internship training. Ir Med J. 2012 Nov;105:328–30.

6.Health Service Executive Medical Education and Training Unit. Implementation of the Reform of the Intern Year: Second Interim Report on the implementation of recommendations of the National Committee report on the Intern Year. 2012 Apr 16:1–72. Available from: https://www.imo.ie/i-am-a/student/intern-placement-2013/Second-Interim-Implementation-Report-April-2012.pdf

7.Irish Medical Council. Your Training Counts: Results of the National Trainee Experience Survey, 2014. 2014. Available from: https://www.medicalcouncil.ie/News-and-Publications/Reports/Your-Training-Counts-Survey.pdf

8.Irish Medical Council. Intern Coordinator and Tutor Network Project Report: A Review of the Intern Year. 2006 Oct. Available from: https://www.medicalcouncil.ie/News-and-Publications/Publications/Information-for-Doctors/Intern-Coordinator-and-Tutor-Network-Project-Report-pdf.pdf

9.Dare A, Fancourt N, Robinson E, Wilkinson T, Bagg W. Training the intern: The value of a pre-intern year in preparing students for practice. Med Teach. 2009 Jan;31:e345–50.

10.Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K, Cameron HS. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of Foundation training? Postgrad Med J. 2011 Aug 23;87:590–5.

11.Goldacre MJ, Taylor K, Lambert TW. Views of junior doctors about whether theirmedical school prepared them well for work:. BMC Med Educ. 2010 Nov 11;10:78.

12.Morrow G, Johnson N, Burford B, Rothwell C, Spencer J, Peile E, Davies C, Allen M, Baldauf B, Morrison J, Illing J.

13. Preparedness for practice: The perceptions of medical graduates and clinical teams. Med Teach. 2012 Feb;34:123–35.

14.Hynes H, Smith S, Henn P, McAdoo J. Fit for practice: Are we there yet? Med Teach. 2012 Mar;34:253–3.

15Ryan C, Ross S, Davey P, Duncan E, Fielding S, Francis J, Johnston M, Ker J, Lee A, Macleod M, Maxwell S, McKay G, McLay J, Webb D, Bond C. Junior doctors' perception of their self-efficacy in prescribing, their prescribing errors and the possible causes of errors. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2013 Dec 76:980-987.

16.Coombes I, Stowasser D, Coombes J, Mitchell C. Why do interns making prescribing error? A qualitative study. Medical journal of Australia. 2008; 188: 89-94.

17.Ryan C, Ross S, Davey P, Duncan E, Francis J, Fielding S, Johnston M, Ker J, Lee A, MacLeod M, Maxwell S, McKay G, McLay J, Webb D, Bond C. Prevalence and causes of prescribing errors: The PRescribing Outcomes for Trainee Doctors Engaged in Clinical Training (PROTECT) Study. 2014 Jan.

18.Smith SE, Tallentire VR, Cameron HS, Wood SM. The effects of contributing to patient care on medical students' workplace learning. Med Educ. 2013 Nov 11;47:1184–96.

19.Gouda P, Fanous S, Gouda J, Boland J, Geoghegan R. Paediatric learning in a clinical attachment: undergraduate medical students' perspectives. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2015.

20.O'Flynn S, Power S, Horgan M, O'Tuathaigh CM. Attitudes towards professionalism in graduate and non-graduate entrants to medical school. Education Health. 2014;27:200-4.

21.Sulong S, McGrath D, Finucane P, Horgan M, O'Flynn S, O'Tuathaigh C. Studying medicine - a cross-sectional questionnaire-based analysis of the motivational factors which influence graduate and undergraduate entrants in Ireland. JRSM Open. 2014 Mar 12;5

22.Brennan N1, Corrigan O, Allard J, Archer J, Barnes R, Bleakley A, Collett T, de Bere SR.The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today’s experiences of Tomorrow’s Doctors. Med Educ. 2010 May;44:449–58.

23.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice Hall; 1986. 1

P387