Cow’s Milk Allergy: A Cohort Of Patients From A University Hospital

A Reynolds1, J O’Driscoll2, S Quinn1, D Coghlan1

1Department of Paediatrics, AMNCH, Tallaght, Dublin 24.

2Department of Nutrition & Dietetics, AMNCH, Tallaght, Dublin 24.

Abstract

Our aim was to establish the feeding history, presentation, management and rate of resolution for an Irish cohort of children with cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) attending a hospital-based outpatient service. This was a cohort study consisting of two parts: a retrospective chart review and a follow-up questionnaire. Fifty-one infants (male: 61%, n=31) were enrolled. Twenty-one (41%) had IgE-mediated allergy. Twenty-nine (57%) had non-IgE mediated allergy. Twenty-two (49%) had tried ≥3 different formulas prior to diagnosis. Of the children who had reached two years, the overall rate of tolerance was 53% (IgE: 35%, non-IgE: 67%). Mild cases of CMPA can be managed in the community. Potential severe complications include faltering growth and anaphylaxis. CMPA should be managed using a multi-disciplinary approach. Increased awareness of CMPA may speed diagnosis and decrease the use of inappropriate formulas.

Introduction

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is an adverse immunological response to cow’s milk protein1. It is one of the most common food allergies in children. The prevalence is difficult to estimate accurately, but population-based studies have found that approximately 2% of children have challenge-confirmed cow’s milk allergy at age one year2. Most children present before 6 months of age and the majority of cases resolve by three years. Although the perceived prevalence is much higher3 than the true prevalence, the condition frequently remains undiagnosed4.

CMPA may be caused by IgE-mediated or non-IgE mediated mechanisms and occasionally by a combination of both. IgE antibodies to cow’s milk proteins produce a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction. Symptoms consistent with a type 1 reaction include acute urticaria, angioedema, wheeze, cough, vomiting and anaphylaxis. Their onset is usually within 1 hour of exposure. Diagnosis is based on clinical history supported by skin prick testing (SPT) or specific IgE (SpIgE) testing. A double-blind food challenge remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of non-IgE CMPA remains poorly understood, but may involve Th2 cell mediated mechanisms5,6. There is currently no accepted laboratory test for non-IgE CMPA7,8. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and elimination followed by, when feasible, oral food challenge9. The history is of a delayed reaction producing gastrointestinal or, occasionally, cutaneous symptoms. Non-IgE CMPA may play a role in a wide array of conditions including eczema, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), colic, constipation and food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES)10-12.

The World Health Organization recommends breastfeeding for all children up to 6 months of age. This recommendation also applies to infants with CMPA. Small numbers of infants may react to the minute concentrations of cow’s milk proteins which can be found in the breast milk of women whose diets contain dairy products13. These infants should respond to a time-defined complete maternal exclusion of cow’s milk. This should be supervised by a dietitian. For formula-fed infants the national and international guidelines recommend an extensively-hydrolysed formula (eHF) as the first line management in mild-moderate CMPA14,15. For formula-fed infants with severe CMPA, defined by the presence of severe atopic eczema, faltering growth, or anaphylaxis, an amino acid formula (AAF) is recommended. An eHF may accelerate resolution of CMPA when compared to an AAF16. Goat’s milk has no role in the management of CMPA17. Concerns about cross reactivity and the presence of phyto-oestrogens limit the use of soya-based formulas18. The aim of this study was to establish the feeding history, presentation, management and rate of resolution for this population.

Methods

This was a cohort study consisting of two parts: a retrospective chart review and a follow-up questionnaire. All children diagnosed with CMPA in the National Children’s Hospital between August 2013 and April 2014 were eligible for inclusion. Subjects were identified from dietetics records. The children enrolled were in-patients or out-patients under the care of general paediatrics, dermatology, gastroenterology or respiratory services at a time when no dedicated allergy service was available locally. Diagnosis of CMPA was based mainly on clinical history, supported by specific IgE testing and elimination ± challenge. Data on feeding history, age of onset, presenting symptoms, type of allergy and choice of hypoallergenic formula was collected by chart review. Faltering growth, as a presenting symptom, was defined as a weight centile >2 centile spaces below length centile or a fall in weight across >2 centile spaces. Anaphylaxis was defined as a severe systemic hypersensitivity reaction, resulting in either respiratory compromise or hypotension. Follow-up was conducted by telephone interview in September 2014. Data was collected on acquisition of tolerance and development of further food allergies. Tolerance was defined as being able to drink 100ml of unaltered cow’s milk or cow’s milk formula regularly without any adverse side effects. Diagnoses of new food allergies were based on a history of a clinical reaction.

Results

Fifty-one infants (male: 61%, n=31) were enrolled. Twenty-one (41%) had IgE-mediated allergy. Twenty-nine (57%) had non-IgE mediated allergy. One patient had a mixed allergy. The median age at onset of symptoms was 3 weeks (interquartile range [IQR]: 0-4 months, range: 0-7 months). For the IgE group, the median age at onset of symptoms was 3 months (IQR: 0-5 months, range: 0-7 months) versus 2 weeks for the non-IgE group (IQR: 0-1 month, range: 0-7 months).

Breastfeeding Patterns

Exclusive breastfeeding was initiated in 32 babies (63%). Of this group, 12 (38%) received formula top-ups in the first week of life. Only 2 babies definitely did not receive formula and the parents of the remaining 18 babies could not recall whether top-up had been given or not. The median duration of exclusive breastfeeding was 5 months (<1 month: 7, 1 month: 1, 2 months: 1, 3 months: 2, 4 months: 4, 5 months: 8, 6 months: 8).

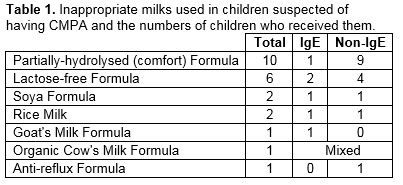

Formula Changes Prior to Diagnosis

The average number of formula changes prior to diagnosis was 1.5 and 2.7 among IgE- and non-IgE-mediated milk allergic infants respectively, with 49% (n=22) having tried ≥3 different formulas (range 1-6). The most common formulas tried were partially-hydrolysed “Comfort” formula, and lactose-free formula. In some cases, these had been recommended by healthcare professionals.

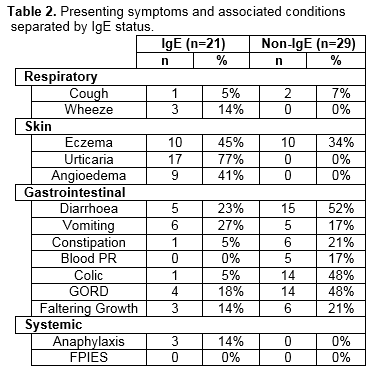

Presenting Symptoms

Among the IgE group, the most common presenting symptoms were urticaria (77%) and angioedema (41%). Ten (45%) had concurrent eczema. Three patients experienced anaphylaxis. Of these, none had been recommended inappropriate formulas. The most common symptoms among the non-IgE group were gastrointestinal. In total, 9 patients (IgE: 3, Non-IgE: 6) had faltering growth.

Additional Allergies

At the time of follow-up, 23 (45%) of the subjects had developed other allergies (IgE: n=16 [76%], Non-IgE: n=7 [24%]). For the IgE group, the most common co-allergies were egg (n=13, 62%) soya (n=4, 19%), legumes (n=3, 14%) peanuts (n=4, 19%), tree nuts (n=4, 19%) and shellfish (n=4, 19%). Three children in the IgE group were poly-allergic and together significantly raised the rate of co-allergy. Among the non-IgE group, rate of allergy was 10% to egg (n=3), 17% to soya (n=5), 3% to legumes (n=1), 3% to peanuts (n=1), 3% to treenuts (n=1).

Choice of Hypoallergenic Formula

On diagnosis, 79% of formula-fed infants (n=30) were recommended an eHF as first line management. Approximately 27% (n=8) of this group later required an AAF due to ongoing symptoms. An AAF was commenced as first line management in 21% of cases (n=8) due to faltering growth (n=2), anaphylaxis (n=1), reactions through breast milk (n=3) and in two cases before assessment at our clinic. Of the 15 infants exclusively or partially breastfed, 8 (53%) required maternal dairy-free diets.

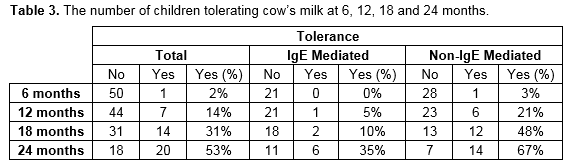

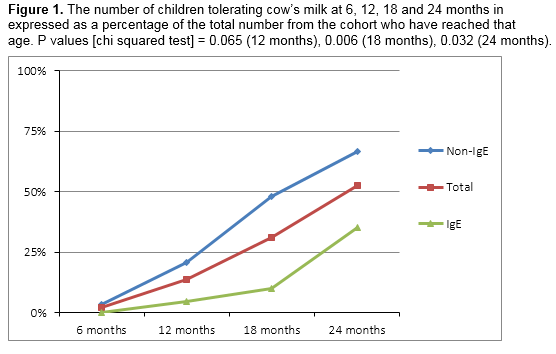

Acquisition of Tolerance

At the time of follow-up, the overall rate of tolerance of cow’s milk was 51% (n=26). The rate of tolerance was 45% (n=9) and 55% (n=16) for the IgE and non-IgE groups respectively. The sole patient with mixed allergy had also achieved tolerance. Table 2 and figure 1 show the number of children from the cohort divided by the age they have reached and whether they are tolerating cow’s milk or not.

Reintroducing Cow’s Milk

Thirty-nine patients (77%) had undergone some form of cow’s milk challenge. Thirty-six patients (71%) had a baked-milk challenge conducted at home. Three (6%) had an in hospital challenge either to baked or unaltered cow’s milk.

Discussion

This is the first Irish cohort of children with CMPA to be described. Overall, these results are in agreement with previous international figures3. All patients presented before 6 months of age. Fifty-seven percent had non-IgE mediated allergy.

Three children (14%) in the IgE group had a history of anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis in response to cow’s milk is rare. Reported rates vary from 0.8% to 9%15. The high figure in this study likely reflects that this population is a selected hospital-based cohort that doesn’t include milder cases managed in the community. Faltering growth was a presenting symptom in 21% of the non-IgE group. Prolonged malnutrition negatively affects growth and cognitive development. On average, children diagnosed with failure to thrive under two years of age have marginally lowers IQs in later childhood, but research in this area is hampered by a multitude of confounding factors19. Ongoing dietetics assessment is essential for infants with faltering growth to ensure that they receive adequate nutrition and gain weight appropriately.

In this study, 38% of infants who went on to exclusively breastfeed received formula top-ups in the first few days of life. Early formula top-ups may be sensitizing events, which increase the likelihood of CMPA20. A recommendation to supplement breastfeeding with formula milk should require a definite medical indication. When supplementation is indicated and the infant is at high risk of developing CMPA, an extensively-hydrolysed formula should be prescribed. Exclusively breastfed infants have a lower incidence of CMPA. Exclusive breastfeeding rates are low in Ireland21. On average parents of children in the non-IgE group changed their child’s formula 3 times before a diagnosis of CMPA was made. The number of formula changes reported suggests a delay in diagnosis and appropriate dietary intervention. The use of inappropriate formulas is a concern. Partially-hydrolysed formulas, marketed as “comfort” formulas, are not suitable for infants with CMPA. Lactose-free formula is recommended for the management of lactose intolerance only. Approximately half of breastfed babies in our study did not require a maternal dairy-free diet. Maternal dietary restrictions, where not necessary, should be avoided to minimise the risk of maternal deficiencies of nutrients such as calcium as well as the burden associated with restricted diets.

Current research suggests that baked milk is well tolerated in the majority of cases22 and that graded introduction of cow’s milk, starting with baked milk, may encourage resolution of CMPA23. The British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology has published guidelines which include recommendations for the reintroduction of cow’s milk24. CMPA is usually a temporary condition. Most cases resolve by three years, but a minority persists into childhood. In this study, 53% of children who had reached 2 years by the time of follow up had acquired tolerance. The rate of co-morbid allergies was high in this study. IgE-mediated CMPA is one of the earliest manifestations of the “atopic march” which can progress to asthma and allergic rhinitis. Children with CMPA are at increased risk of developing other food allergies, some of which are more persistent than CMPA and carry a greater risk of anaphylaxis.

This is partly a retrospective study and the associated limitations apply. The patients in this study are likely representative of patients attending general paediatrics services across the country. Limited resources and parental reluctance restrict the number of challenges that can be performed to confirm the diagnosis of non-IgE CMPA. Identification of additional allergies was based on clinical assessment of reported symptoms rather than skin-prick testing, specific IgE levels or food challenge.

The management of allergies is changing. In the past decade, there has been increasing interest in tolerance acquisition and allergy prevention. Mild cases of CMPA can be managed successfully in the community. This could be facilitated by greater availability of community dietetics services. Increased awareness of CMPA may help expedite its diagnosis and decrease the inappropriate use of formulas not recommended for the management of CMPA.

Correspondence: A Reynolds

Department of Neonatology, Cork University Maternity Hospital, Wilton, Cork

E-mail: [email protected]

References:

1. Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, Motala C, Ortega Martell JA, Platts-Mills TA, Ring J, Thien F, Van Cauwenberge P,Williams HC. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:832-6.

2. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:291-307

3. Venter C,Pereira B,Voigt K, Grundy J, Clayton CB, Higgins B, Arshad SH, Dean T. Prevalence and cumulative incidence of food hypersensitivity in the first 3 years of life. Allergy. 2008;3:354–359

4. Eggesbø M, Botten G, Halvorsen R, Magnus P. The prevalence of CMA/CMPI in young children: the validity of parentally perceived reactions in a population-based study. Allergy. 2001;56:393-402.

5. Shek LP, Bardina L, Castro R, Sampson HA, Beyer K. Humoral and cellular responses to cow milk proteins in patients with milk-induced IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated disorders. Allergy. 2005;60:912-9.

6. Beyer K, Castro R, Birnbaum A, Benkov K, Pittman N, Sampson HA. Human milk-specific mucosal lymphocytes of the gastrointestinal tract display a TH2 cytokine profile. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:707-13.

7. Canani RB,Ruotolo S,Auricchio L, Caldore M, Porcaro F, Manguso F, Terrin G, Troncone R. Diagnostic accuracy of the atopy patch test in children with food allergy-related gastrointestinal symptoms. Allergy. 2007;62:738-43.

8. Hochwallner H,Schulmeister U,Swoboda I, Twaroch TE, Vogelsang H, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Kundi M, Balic N, Quirce S, Rumpold H, Fröschl R, Horak F,Tichatschek B, Stefanescu CL, Szépfalusi Z, Papadopoulos NG, Mari A, Ebner C, Pauli G, Valenta R, Spitzauer S. Patients suffering from non-IgE-mediated cow's milk protein intolerance cannot be diagnosed based on IgG subclass or IgA responses to milk allergens. Allergy 2011;66:1201-7.

9.Venter C, Brown T, Shah N, Walsh J, Fox AT. Diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy in infancy - a UK primary care practical guide. Clin Transl Allergy. 2013;3:23.

10. Fiocchi A, Bouygue GR, Martelli A, Terracciano L, Sarratud T. Dietary treatment of childhood atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome (AEDS). Allergy. 2004;59:78–85.

11. Heine RG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, colic and constipation in infants with food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:220–225.

12. Sicherer SH. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: case presentations and management lessons. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:149–156.

13. Host A, Husby S, Hansen LG, Osterballe O. Bovine beta-lactoglobulin in human milk from atopic and non-atopic mothers. Relationship to maternal intake of homogenized and unhomogenized milk. Clin Exp Allergy 1990;20:383–7.

14. Irish Food Allergy Network (IFAN) Paediatric Food allergy: Care pathway for the diagnosis and management of Cow’s Milk Allergy 2012

15. Fiocchi A, Brozek J, Schünemann H, Bahna SL, von Berg A, Beyer K, Bozzola M,Bradsher J, Compalati E, Ebisawa M, Guzman MA, Li H, Heine R G,,Keith P, Lack G, Landi M, Martelli A, Rancé F, Sampson H, Stein A, Terracciano L, Vieths S, World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow's Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21 Suppl 21:1-125.

16. Jung-Wu S. Formula Selection for Management of Children With Cow's Milk Allergy Influences the Rate of Acquisition of Tolerance: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Pediatrics. 2014;134 Suppl 3:S154-5.

17. Bellioni-Businco B,Paganelli R,Lucenti P, Giampietro PG, Perborn H, Businco L. Allergenicity of goat's milk in children with cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103:1191.

18. Bhatia J, Greer F. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1062–8.

19. Rudolf MC, Logan S. What is the long term outcome for children who fail to thrive? A systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:925-31.

20. Liao SL,Lai SH,Yeh KW, Huang YL, Yao TC, Tsai MH, Hua MC, Huang JL; PATCH (The Prediction of Allergy in Taiwanese Children) Cohort Study, Exclusive breastfeeding is associated with reduced cow's milk sensitization in early childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014; 25:456.

21. Joint ESRI/HSE National Office of Health Promotion Conference. Breastfeeding in Ireland 2012: Consequences and Policy Responses.

22. Nowak-Wegrzyn A,Bloom KA,Sicherer SH, Shreffler WG, Noone S, Wanich N, Sampson HA.. Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:342-7, 7.e1-2.

23. Kim JS, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sicherer SH, Noone S, Moshier EL, Sampson HA. Dietary baked milk accelerates the resolution of cow's milk allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;12v:125-31.e2.

24. Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, Clark, AT. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow's milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:642-72.

P390