The Prolonged Neonatal Admission: Implications for our National Children's Hospital

SM McGlacken-Byrne, L Geraghty, JFA Murphy

Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street, Dublin

Abstract

A significant number of neonates are admitted to tertiary paediatric units for prolonged stays annually, despite limited availability of neonatal beds. As the three Dublin paediatric hospitals merge, this pressure will be transferred to our new National Children’s Hospital.

We analysed epidemiological trends in prolonged neonatal admissions to the 14-bed neonatal unit in The Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street, Dublin. This was with a view to extrapolating this data toward the development of a neonatal unit in the National Children’s Hospital that could accommodate for this complex, important, and resource-heavy patient population.

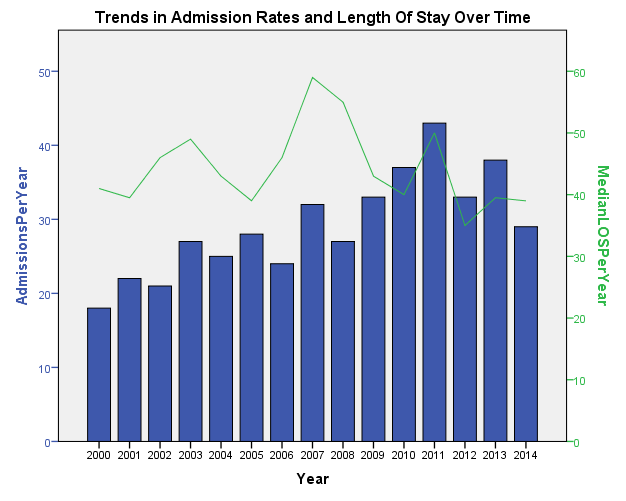

Four hundred and thirty-six babies between 0 and 28 days of life were admitted to our neonatal unit for prolonged stays (three cohorts: >1 month and <3months, >3months and <6months, and >6months), between 2000-2014. Mean number of prolonged admissions >1 month was 29.1 per year (range 18-43). Median length of stay (LOS) was 42 days (range 29-727). 363 babies were admitted for >1month but <3months with a median LOS 38 days (range 28-90); 54 babies were admitted for >3months but <6months with a median LOS 111 days (range 91-179); 19 babies were admitted for >6months with a median LOS 331 (range 196-727). There has been a statistically significant upward trend in the number of prolonged admissions over last fifteen years (Spearman’s rho p=0.01, correlation coefficient 0.848). There has been no significant increase in the median length of stay over time. It can be extrapolated, that in the new children’s hospital must be capable of dealing with at least 80 neonatal long-stay patients annually.

Introduction

The Children’s University Hospital in Temple Street admits approximately 8000 children per year. Nationally, up to 28,000 children are admitted per year to paediatric units around the country. Fortunately, most of these admissions are short; resources such as nurse specialists, home antibiotic therapy and insulin pump therapy have facilitated community-based care of these children.

Neonates with chronic illnesses often have complex needs requiring multidisciplinary input. Consequently, a significant number of neonates are admitted to tertiary paediatric units for prolonged stays. Beds in our neonatal wards are limited, with a constant influx of acutely unwell infants from surrounding maternity hospitals. As the three Dublin paediatric hospitals merge, this pressure will be transferred to the new National Children’s Hospital.

Methods:

We analysed epidemiological trends in prolonged neonatal admissions to our 14-bed neonatal unit in Temple Street with the aim of using this data to inform the development of the neonatal unit in the National Children’s Hospital.

We reviewed data on any infant admitted between 0-28 days of life over a 15 year period (2000-2014), considering them in three cohorts: prolonged admissions of >1 month and <3months, >3months and <6months, and >6months (n = 436). The mean number of prolonged admissions >1 month was 29.1 per year (range 18-43). Median length of stay (LOS) was 42 days (range 29-727 days).

Results:

Three hundred and sixty-three babies were admitted for >1month but <3months with a median LOS 38 days (range 28-90); 54 babies were admitted for >3months but <6months with a median LOS 111 days (range 91-179); 19 babies were admitted for >6months with a median LOS 331 (range 196-727).

There has been a statistically significant upward trend in the number of prolonged admissions over the last fifteen years (Spearman’s rho p=0.01, correlation coefficient 0.848). There has been no significant increase in the median LOS over time.

Discussion

These figures demonstrate the increasing trend in prolonged admissions to our neonatal unit, and suggests that our new children’s hospital should be capable of dealing with at least 80 neonatal prolonged admissions per year.

The adverse effects associated with prolonged admissions are well-described: the developmental impact of bright lights and noise1, nosocomial infections, and missed opportunities for oral feeding2.Separation of caregiver and baby comes at a personal and financial cost to caregivers3. The financial pressure on hospital resources is also significant: based on recent hospital data, the cost of an overnight stay in the HDU neonatal ward is at least €820. This is a conservative estimate, as this figure only includes the price of a bed on the HDU ward for 24 hours. It does not include the additional cost of consultant review, imaging, allied health professionals input, imaging, or one-on-one nursing. Therefore, the minimum ward cost for a baby staying for our average of 42 nights is €35,000. The true figure is likely twice this when all costs are incorporated. Furthermore, these admissions create significant bed management issues, particularly when accommodating transfers from the emergency department, maternity hospitals, and peripheral units.

Despite these pressures, our study shows that there are multiple prolonged neonatal admissions annually. These pressures will be transferred over to the new hospital, multiplied by at least three-fold as the paediatric hospitals combine. While some infants require a prolonged in-hospital admission, it would be prudent going forward to make efforts to reduce avoidable prolonged neonatal admissions. Some of our cohort may have been discharged earlier had the necessary supports been available.

Preparation for discharge begins on admission4. Discharge Planning nurses are invaluable as many of these babies have complex needs that require multi-speciality input. A “checklist” based individualised approach to discharge need to be implemented from early on5 and has been successfully implemented in many units6. These discharge proformas are more useful when they are patient-specific7, as the family can be involved from the beginning in the planning of care tailored to their baby’s specific needs.

Indeed, family-centred, holistic care is long established as an aid to early discharge of infants from neonatal units. There is little point in optimising the baby for discharge from a medical perspective if the parents do not have the skills nor confidence to look after their child at home. “Parental role alterations” – the transition from “visitor” to “primary carer” – has been cited as the most stressful factor for families approaching discharge8. Parents worry that they will not be able to recognise a deterioration in their child. However, parental education is time consuming. While most parents visit their baby as often as they can, they have commitments outside the world of the hospital. The neonatal units are busy, often with limited staff, acutely unwell patients, and strict visiting hours. While family-centred, nurse-led care brings babies nearer to discharge9, it can be hard to find the opportunity to meet with parents in the first instance. Indeed, while obviously essential in preventing nosocomial infections, strict visiting hours are a key barrier to early discharge from neonatal units10. Discharge planning nurses can work with the family to find a time that suits to meet. Lastly, language barriers can significantly impair opportunities for parental education11. Unfortunately, short-notice translators can be in short supply.

While a discharge proforma is useful in coordinating care, parental confidence and competence cannot be monitored using a “tick-box” approach. The relationships built up with staff over the weeks and months support caregivers in their journey towards home. Discharge from the NICU is expedited not only by parental “acquisition of knowledge and skills” but also by “facilitating [their] comfort and confidence”12.

Despite a unit’s best efforts, community structures to support earlier discharge of the baby are simply not available. Barriers to discharge are frequently feeding related or airway related. These are potentially manageable within the community with the support of home care nurses, financial grants, and satellite community paediatric units. Caregivers of a recently discharged infant need ongoing social and emotional support from primary care services: adapting to parenting of these babies at home can take months13.

Babies who feasibly could be managed in the community, remain in hospital due to lack of necessary resources. Strong links between community and hospital resources have been identified as key in implementing a well-functioning early discharge plan10. The development of the new children’s hospital has heralded discussions on how to strengthen these ties between our community and hospital paediatric services; perhaps in the future some of the prolonged neonatal admissions will be avoided. In the interim, however, we must remain cognisant of these babies – and of the concept of the prolonged neonatal admission – when developing the new children’s hospital.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors report there are no conflicts of interest associated with this article

Correspondence:

Sinead McGlacken-Byrne

Children's University Hospital, Temple St, Dublin

s.mcglackenbyrne1@nuigalway.ie

References

1. Vasquez-Ruiz S, Maya-Barrios JA, Torres-Narvaez P, Vega-Martinez BR, Rojas-Granados A, Escobar C, Angeles-Castellanos, M. A light/dark cycle in the NICU accelerates body weight gain and shortens time to discharge in preterm infants. Early Human Development. 2014;90: 535-540.

2. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Meinzen-Derr JK, . Missed oral feeding opportunities and preterm infants' time to achieve full oral feedings and neonatal intensive care unit discharge. American Journal of Perinatology. 2015;32:1-8.

3. Merritt T, Pillers D, Prows SL. Early NICU discharge of very low birth weight infants: a critical review and analysis. Seminars in Neonatology. 2002;8:95-115.

4. Schlittenhart J, Smart D, Miller K, Severtson B. Preparing parents for NICU discharge: an evidence-based teaching tool. Nursing for Women’s Health. 2011;15:484-494.

5. Peacock J. Discharge summary for medically complex infants transitioning to primary care. Neonatal Network. 2014;33:204-207.

6. Brodsgaard A, Zimmermann R, Petersen M. A preterm lifeline: Early discharge programme based on family-centred care. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2015;20:232-43.

7. Burnham N, Feeley N, Sherrard K. Parents' perceptions regarding readiness for their infant's discharge from the NICU. Neonatal Network. 2013;32:324-334.

8. Raines D. Mothers' stressor as the day of discharge from the NICU approaches. Advances in Neonatal Care. 2013;13:181-187.

9. Whyte R. Neonatal management and safe discharge of late and moderate preterm infants. Seminars In Fetal And Neonatal Medicine. 2012;17:153-158.

10. Raffray M, Semenic S, Galeano SO, Marin SC. Barriers and facilitators to preparing families with premature infants for discharge home from the neonatal unit. Perceptions of health care providers. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. 2014;32:379-392.

11. Enlow E, Herbert SL, Jovel IJ, Lorch SA, Anderson C, Chamberlain LJ. Neonatal intensive care unit to home: the transition from parent and paediatrician perspectives, a prospective cohort study. Journal of Perinatology. 2014;34:761-766.

12. Smith VC, Hwang SS, Dukhovny D, Young S, Pursley DM. Neonatal intensive care unit discharge preparation, family readiness and infant outcomes: connecting the dots. Journal of Perinatology. 2013;33:415-421.

13. Gardner M. Maternal caregiving and strategies used by inexperienced mothers of young infants with complex health conditions. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2014;43:813-823.

p428