Dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcaemia in the Irish paediatric population. A case report.

S Glackin1,2, P Mayne2,3, D Kenny4, CJ McMahon4, D Cody1

1 Department of Endocrinology, Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland

2 Children's University Hospital, Temple St, Dublin 1, Ireland

3 Department of Biochemistry, Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland

4 Department of Cardiology, Our Lady's Children's Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland

Abstract

We identified three infants with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) secondary to severe vitamin D deficieny and hypocalcaemia. All infants were exclusively breast fed, from dark skinned ethnic backgrounds, born and living in Ireland. None of these pregnant mothers or infants received the recommended vitamin D supplementation. Each infant presented in heart failure and required inotropic support as well as calcium and vitamin D replacement. Cardiac function subsequently improved. This highlights the public health issue that many high risk pregnant mothers and infants are not receiving the recommended vitamin D supplementation.

Introduction

The primary source of vitamin D is sunlight, though it can also be derived from dietary sources. Vitamin D synthesis depends on factors such as the amount and duration of exposed skin, skin type, sunscreen, latitude and cloud cover. Vitamin D synthesis is reduced by melanin and is more efficient in pale skin than darker skin. Women from sunny climates who cover their faces and hands are at high risk of vitamin D deficiency1. Therefore people from dark skinned ethnic backgrounds living in Ireland at high latitude, with minimal sunlight exposure are at high risk of vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency is determined as 25(OH) D3 levels <30 nmol/L and insufficiency as 25(OH) D3 levels 30-50 nmol/L2 . Vitamin D has vital roles in bone health and cell growth. The active hormone, calcitriol regulates calcium, an essential ion for cell function. Vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcaemia can lead to DCM, rickets, myopathy, tetany, osteomalacia and seizures.

Case report

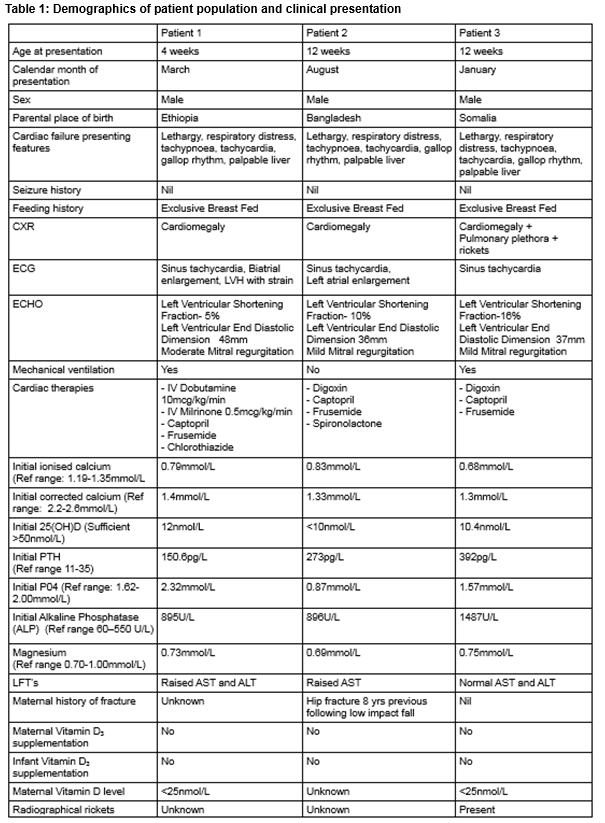

We identified three infants over a 9-year period with DCM secondary to vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcaemia who presented in cardiac failure (Table 1). Each infant was exclusively breast fed and from a dark skinned ethnic background. None of the infants or their mothers during pregnancy had received the recommended vitamin D supplementation.

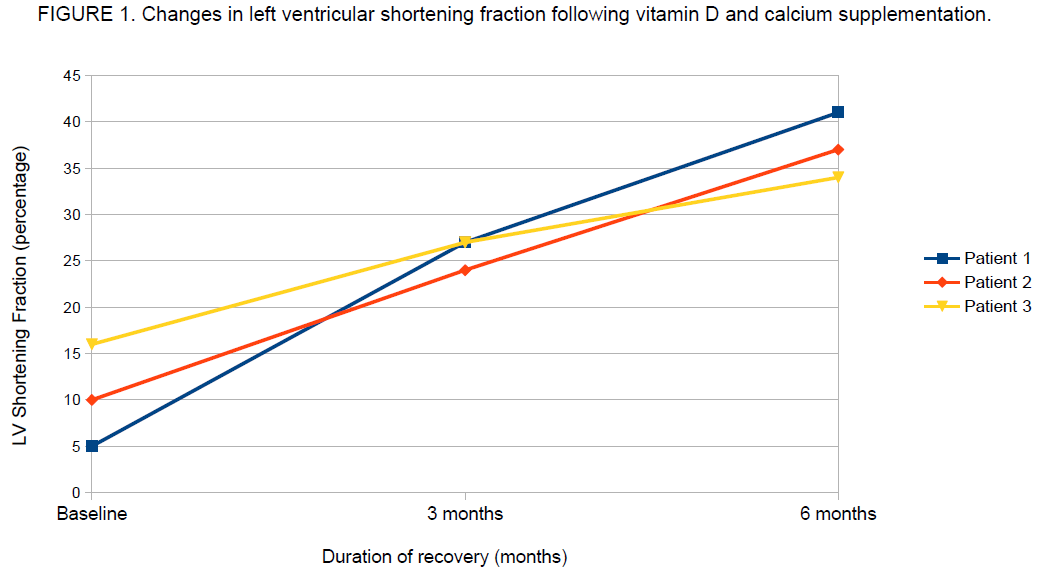

The echocardiography of each infant demonstrated a dilated left ventricular (LV) cavity with markedly reduced LV systolic function. The median LV shortening fraction measured 10% (5-16%). Each infant received a combination of diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (captopril) and cardiac glycosides (digoxin). One infant initially required intravenous (IV) inotropic support. Each infant required IV calcium for up to 5 days with subsequent oral calcium treatment. They were all treated with oral vitamin D for between 6 and 12 months. Following 6 months of vitamin D and calcium replacement, the LV shortening fraction normalised to a median of 37% (34-41%) and they were all subsequently weaned off inotropic support (Fig1).

Discussion

A 2008 case series from England identified 16 breast-fed infants (3 weeks-8 months) with heart failure secondary to vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcaemia, all from dark skinned ethnic backgrounds3. Three of these infants died. None of the pregnant mothers and no infants had received the recommended vitamin D supplementation. Shortening fraction normalised at a mean of 12.4 months on vitamin D and calcium replacement, longer than in our report.

During pregnancy, if mothers are vitamin D deficient, foetal calcium and phosphorous levels are normal. However, at birth their infants will be vitamin D deficient and without the recommended vitamin D supplementation, they will become hypocalcaemic4. Therefore, pregnant women are advised to receive 600IU/day of vitamin D supplementation2.

There is low transfer of maternal vitamin D and 25(OH) D3 and no transfer of calcitriol into breast milk5. The vitamin D concentration in breast milk ranges from 25-78 IU/L in non supplemented mothers to 800 IU/L in mothers on high dose vitamin D supplementation5. However, lactating mothers are advised to receive 600IU/day of vitamin D from dietary sources, and not to take high dose vitamin D supplementation due to toxicity concerns2. All infants are recommended to receive 400 IU/day vitamin D supplementation up to 12 months, regardless of type of feeding2. Estimated compliance for this in Ireland is approximately 59%6 Infants should also receive calcium rich complementary foods from no later than 26 weeks.

These three infants had DCM secondary to severe vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcaemia. This sends a public health message to healthcare professionals about the importance of supplementing all pregnant mothers and infants up to 12 months. This message should be emphasised, in appropriate languages, to those at high risk of vitamin D deficiency such as dark-skinned mothers with limited sunlight exposure.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest in this paper.

Correspondence:

Dr. Sinead Glackin, Endocrine and Diabetes Unit, BC Children’s Hospital, 4480 Oak St. Vancouver, BC V6H 3V4

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +17782332137

Acknowledgement:

The families of each patient were contacted, and written informed consent was obtained from each family.

References:

1 F. Alagol, Y. Shihadeh, H. Boztepe, R. Tanakol, S. Yarman, H. Azizlerli, O. Sandalci. Sunlight exposure and vitamin D deficiency in Turkish women. J Endocrinol Invest 2000;23:173–7.

2. CF. Munns, N. Shaw, M. Kiely, B.L Specker, T.D. Thacher, K. Ozono, T. Michigami, D. Tiosano, M.Z. Mughal, O. Makitie, L. Ramos-Abad, L. Ward, L.A Dimeglio, N. Atapattu, H. Cassinelli, C. Braegger, J.M Pettifor, A. Seth, H.W. Idris, V. Bhatia, J. Fu, G. Goldberg, L. Savendahl, R. Khadgawat, P. Pludowski, J. Maddox, E. Hypponen, A. Oduwole, E. Frew, M. Aguiar, T. Tulchinsky, G. Butler, W. Hogler. Global Consensus Recommendations on Prevention and Management of Nutritional Rickets. J Clin Endcorinol Metab, February 2016, 101 (2):394-415

3. Maiya S.,Sullivan I., Allgrove J., Yates R., Malone M., Brain C., Archer N., Mok Q., Daubeney P., Tulloh R., Burch M. Hypocalcaemia and vitamin D deficiency: an important, but preventable, cause of life-threatening infant heart failure. Heart 2008;94:581–584. doi:10.1136/hrt.2007.119792

4. Kovacs C.S. Maternal vitamin D deficiency: Fetal and neonatal implications. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 18 (2013) 129e135

5. Hollis B, Wagner C., Howard C., Ebeling M, Shary J, Smith P, Taylor S, Morella K, Lawrence R. Hulsey T. Maternal Versus Infant Vitamin D Supplementation During Lactation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Paediatrics 2015;136;625-634.

6. Hogler W., Complications of vitamin D deficiency from the foetus to the infant: One cause, one prevention, but who's responsibility? Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 29 (2015) 385e398

P535