Aggressive Recurrence of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a patient with Fanconi’s Anaemia (FA)

M Nolan, R Courtney, P Sexton, T Barry, PJ McCann

Oral & Maxillofacial Department, Galway University Hospitals, Galway

Abstract

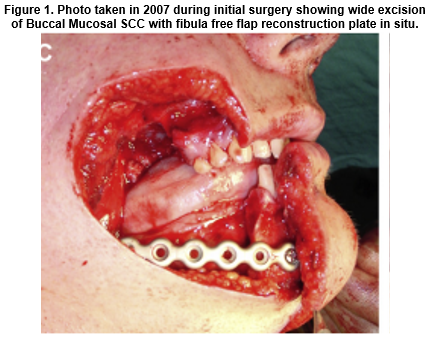

Fanconi’s Anaemia is a rare autosomal recessive disease for which the incidence of head and neck cancer can be increased 700-fold1. We report a case of a 31-year old Caucasian male with FA who initially presented in July 2007 with oral squamous cell carcinoma for which he received radical surgery and radiotherapy. He was disease-free until August 2015 when he presented with an extremely aggressive recurrence.

Introduction

FA is a rare autosomal recessive disease that was first described by Guido Fanconi in 1927. There is an estimated incidence of 1:360,000 births1. This disease is characterized by short stature, various congenital abnormalities and progressive bone marrow failure, leading to death or the need for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Patients with FA have a short life expectancy, mainly because they develop malignancies such as leukaemia and oral squamous cell carcinomas at a young age2. The behaviour and management of the FA patient appears to differ with the general population because of the patient's hypersensitivity to DNA crosslinking agents and radiation therapy2.

CASE REPORT

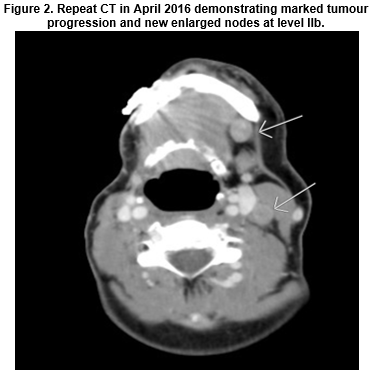

Our case involves a 31-year old man with a strong familial history of FA. His sister with FA had passed away previously due to leukaemia. Diagnosed at 5 years old, he underwent chemotherapy and had a bone marrow transplant at 12 years old. Only classic signs of FA were short stature and limb hypoplasia. He was a non-smoker and non-drinker with good family support. Initial OSCC presentation was in 2007 with SCC of right buccal mucosal/ commissural region necessitating right mandibulectomy, partial maxillectomy, selective neck dissection and fibula free flap. He then received post-operative radiotherapy and was disease free until August 2015. Presented with t4 SCC right tongue, extending to base of tongue and displacing the epiglottis posteriorly. Enlarged nodes in levels 2, 3 and 5 were noted on MRI. Initially thought to be unresectable but after MDM discussion, given two cycles of 80% reduced dose cisplatin with 5FU and cetuximab. He developed severe neutropenic sepsis and chemotherapy was discontinued. A repeat CT was performed in April 2016 which showed marked progression of the tumour. Despite the diminished prognostic outcome, the patient was extremely keen to exhaust all surgical options. Radical surgery including tracheostomy, total glossectomy, left neck dissection, and reconstruction with a latissimus dorsi free flap was carried out in May 2016. Removal of previous fibula graft and overlying paddle flap, excision of epiglottis and tonsillar tissue was required as well as further resection of mandible. Patient recovered well post-operatively however, resective pathology demonstrated a T4bN2cM0, 9 metastatic nodes with extra-capsular spread, positive margins at multiple sites and extension at the skull base could not be ruled out.

There was extensive lymphovascular and perineural invasion with the tumour replacing almost all of the tongue. The patient presented for a four week review following discharge with extensive tumour recurrence visible on the flap with repeat CT confirmation. He has been transferred to the palliative care team.

DISCUSSION

Our case demonstrates the potential for aggressive OSCC presentation in the FA patient and the severity of its recurrence. The primary cause of mortality in post-bone marrow transplant survivors and in non-transplanted FA adults is oral/oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma3. A two to four fold increased risk and earlier development (mean range, 18-33 years) of head and neck SCC have been reported in patients with FA after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) compared with those who receive no transplant4. Solid cancer management is more difficult in patients with FA than in the general population because of their increased sensitivity to chemotherapy with DNA crosslinkers and the variable but potentially increased side effects from radiotherapy5. Recommendations drawn up by the Fanconi Hope Charitable Trust in 2009 include, vaccinating all FA-affected patients against HPV, examining for OSCC and pre-cancerous lesions 4 times a year from age 10 by a head and neck cancer surgeon and treatment by radical excision in light of intolerance to chemo/radiotherapy3. Routine and accurate mouth-self-examination should be recommended as a strategy to detect OSCC4. Unfortunately, despite employing extreme diligence with the FA patient, the aggressive nature of the disease can be inexorable.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Correspondence

Dr Michael Nolan, Leagaun, Moycullen, Co.Galway.

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Jiahui.L, Kutler D.I, Why Otolaryngologists Need to be Aware of Fanconi Anaemia, Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2013; 46: 507-718.

2. Cavalcanti. L.G, FA.K, Lyko. T, Araujo. R.L.F, Amenabar. J.M, Bonfim.C, Torres-Pereira. C.C, Oral Leukoplakia in Patients With Fanconi Anaemia Without Hematopoietic, Pediatr Blood Cancer .2015; 62:1024–1026.

3. Carroll.R, Vora.A, McMahon.J. Fanconi Anaemia and Oral Cancer: UK Standards of Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2010; 22: 895-900.

4. Furquim CP, Pivovar A, Cavalcanti LG, Araújo RF, Bonfim CM, Torres-Pereira CC. Mouth self-examination as a screening tool for oral cancer in a high-risk group of patients with Fanconi anemia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:440-6.

5. Kutler DI, Singh B, Satagopan J, Batish SD, Berwick M, Giampietro PF, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD. A 20-year perspective on the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (IFAR). Blood. 2003;101:1249-56.

P533