An Analysis of Gender Diversity in Urology in the UK and Ireland

E M O’Connor 1, G J Nason1, RP Manecksha2,3

1Department of Urology, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

2Department of Urology, St James’ Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland

3Department of Urology, Tallaght Hospital, Dublin 24, Ireland

Abstract

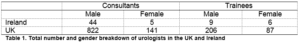

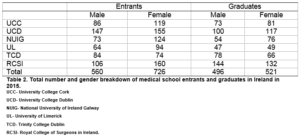

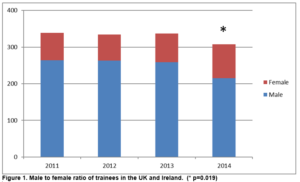

Traditionally, surgery and certain surgical sub-specialities in particular have been predominantly male orientated. In recent years, there has been an increased proportion of female medical graduates which will ultimately have an effect on speciality choices. The aim of this study was to assess the gender diversity among urologists in the UK and Ireland. The total number and gender breakdown of consultant urologists and trainees in the UK and Ireland was obtained from the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) and the Irish Society of Urology (ISU) membership offices. The total number and gender breakdown of medical school entrants and graduates in 2015 was obtained from the six medical schools in the Republic of Ireland. There are a total of 1,012 consultant urologists in the UK and Ireland. In the UK, 141 (14.6%) are female compared to four (8.2%) in Ireland, p= 0.531. There was a significant increase in the number of females between consultant urologists and trainees in both the UK (p=0.0001) and Ireland (p=0.015). In recent years, there has been a significant change in the percentage of female trainees in the UK and Ireland (22.8% (n=75) in 2011 vs 31.7% (n=93) in 2014, p=0.019. Between the six medical schools in Ireland, there were significantly more female entrants (n=726, 56.5%) than female graduates (n=521, 51.2%) in 2015, p=0.013.There has been a significant shift in gender diversity in urology in the UK and Ireland. Efforts to increase diversity should be pursued to attract further trainees to urology.

Introduction

An increase in gender and ethnic diversity in medicine has been associated with high quality medical education, greater research productivity, improved business solvency and improved access to healthcare resources for the lower socio-economic demographics1. Traditionally, surgery and certain surgical sub-specialities in particular (orthopaedics, neurosurgery and urology) has been predominantly male orientated2,3. However in recent years, there have been an increased proportion of female medical graduates which will ultimately have an effect on speciality choices. A recent study of medical students and junior doctors in the UK demonstrated females were significantly less likely to consider urology as a career choice4.

Recruiting more females to urology remains an important issue for physicians and patients. Striving to increase the number of female urologists will help attract the top medical students and will create a diverse learning and working environment5. Female physicians are more likely to bring diverse perspectives to research and to pursue research on sex issues6. Additionally, patients are more satisfied with their treatment and ability to communicate with physicians of the same sex and race. Given the variation in urological conditions including some that affect women more than men, understanding how to more effectively recruit and train female urologists to address the gender disparity in our field should be of vital concern7. The aim of this study was to assess the gender diversity among urologists and trainee urologists in the UK and Ireland.

Methods

The total number and gender breakdown of consultant urologists and trainees in the UK and Ireland was obtained from the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) and the Irish Society of Urology (ISU) membership offices. In the UK, only trainees with a national training number were identified (ST3 and above). In Ireland, trainees enrolled in the urology higher surgical training (HST) program (equivalent to ST3 and above) were identified. The total number and gender breakdown of medical school entrants (commencing September/October 2015) and graduates (graduating May/June 2015) was obtained from the six medical schools in the Republic of Ireland (University College Cork (UCC), University College Dublin (UCD), University of Limerick (UL), National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG), Trinity College Dublin (TCD) and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI). The number of medical school entrants and graduates was compared from 2005 and 2015, excluding the RCSI as data from 2005 was unavailable. Furthermore, postgraduate medical enrolment was not possible in 2005. In Ireland, the duration of a medical degree varies between four years for postgraduate enrolment and five or six years for undergraduate enrolment. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6. Fisher’s exact test was used in the analysis of contingency tables. A p-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

There are a total of 1,012 consultant urologists in the UK and Ireland. In the UK, 141 (14.6%) are female compared to four (8.2%) in Ireland, p= 0.531. There are a total of 308 urological trainees (ST3 and above) in the UK (n=293) and Ireland (n=15). In the UK, 87 (29.7%) are female compared to six (40%) in Ireland, p= 0.398. There was a significant increase in the number of females between consultant urologists and trainees in both the UK (p=0.0001) and Ireland (p=0.015), Table 1. In recent years, there has been a significant change in the percentage of female trainees in the UK and Ireland (22.8% (n=75) in 2011 vs 31.7% (n=93) in 2014, p=0.019), Figure 1.

Between the six medical schools in Ireland, there were significantly more female entrants (n=726, 56.5%) than female graduates (n=521, 51.2%) in 2015, p=0.013, Table 2. There is no difference in the male to female ratio of entrants (p=0.144) or graduates (p=0.109) when comparing 2005 and 2015, Table 3.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate there has been an increasing trend of female trainees choosing urology as a career path in recent years. There are significantly more female trainees compared to consultant urologists in the UK and Ireland, highlighting the change in gender diversity within the speciality. Traditionally urology has been viewed as one of the male dominated surgical specialities. With the growing number of female medical school entrants and graduates surgical specialities will need to dedicate time and resources to attracting trainees to meet their service needs going forward.

There has been a growing concern regarding the reduced exposure to urology at undergraduate level8. In the UK, Malde et al, reported that 26% of medical students had no urology attachment throughout their clinical clerkships, while 30% completed a one week urology attachment9. In a survey of US medical school directors, 65% agreed it was possible to complete their program without any clinical exposure to urology10. A recent study of medical students and junior doctors in the UK demonstrated less than half of the respondents felt they received a good level of exposure to urology whereas only 37% felt confident with basic urological skills such as male catheterisation4. Structured training programmes in practical skills such as catheterisation prior to the commencement of intern year has been shown to result in a significant decrease in the amount of iatrogenic urethral catheterisation related morbidity11.

There is strong evidence that medical students decide their future medical career during medical school12. This choice however can change over the course of the undergraduate course. Many factors influence medical student’s career choice13,14. These factors are classified into two groups- intrinsic factors- related to the students’ personal attributes and preferences and extrinsic factors such as work environment, peers and experiences. Numerous studies have demonstrated that early clinical clerkships are an important aspect in a student’s career choice, O’Herrin et al noted a two fold increase in the number of students interested in a surgical residency following a third year clerkship15. Mentors or role models at an early stage are important in student and junior doctors’ career choice. Residents as well as attending staff are equally important as role models to students.16 Bongiovanni et al highlighted a scarcity of role models as a key factor in the high rates of attrition from surgical residencies17. Speciality choice is also influenced by factors such as gender18, personality19, and perceptions regarding job-related factors such as work-life balance20.

Several studies have demonstrated a gender difference with regards to speciality choice21,22. There are many suggested explanations as to the causes of the continued low rate of women entering the field of surgery including work-life balance, family, lack of female role models/mentors, lack of exposure23,24. Templeton et al cited family-leave issues, unsupportive leadership, and the lack of senior-rank female mentors as factors that might influence the residency selection decisions of female medical students or the promotion of junior faculty to senior ranks25. Providing more exposure to urology at medical school level will increase awareness and interest in urology as a speciality.

Our study is limited by the fact we focused our analysis of urological trainees at ST3 level and above, which does not take into account more junior trainees or non-scheme registrars. ST3 trainees are on a dedicated training path to become consultant urologists and we felt this is probably more representative of future consultant urologists. Furthermore, only details of registered trainees were available from the ISU and BAUS membership offices. There has been a significant shift in gender diversity in urology in the UK and Ireland. Currently, almost a third of urology trainees are female. Further efforts to increase diversity should be pursued to attract further trainees to urology.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Correspondence:

Ms Eabhann O’Connor, Specialist Registrar in Urology, Department of Urology, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork, Ireland

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +353214922000

References

1. Simon MA. Racial, ethnic and gender diversity and the resident operative experience. How can the Academic Orthopaedic Society shape the future of orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999 Mar;(360):253-9.

2. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R, Chapman CH, Both S, Thomas CR Jr. Diversity in graduate medical education in the United States by race, ethnicity, and sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Oct 1;175(10):1706-1708.

3. Day CS, Lage DE, Ahn CS. Diversity based on race, ethnicity, and sex between academic orthopaedic surgery and other specialties: a comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Oct 6;92(13):2328-35.

4. Jones P, Rai BP, Qazi HA, Somani BK, Nabi G. Perception, career choice and self-efficacy of UK medical students and junior doctors in urology. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015 Sep-Oct;9(9-10):E573-8.

5. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, Wilkerson L. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

6. White AA 3rd. Resident selection: are we putting the cart before the horse? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002 Jun;(399):255-9.

7. Prodromos CC, Han Y, Rogowski J, Joyce B, Shi K. A meta-analysis of the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender, sport, and a knee injury-reduction regimen. Arthroscopy. 2007 Dec;23(12):1320: e6.

8. Slaughenhoupt B, Ogunyemi O, Giannopoulos M, Sauder C, Leverson G. An update on the current status of medical student urology education in the United States. Urology. 2014;84:743-7.

9. Malde S, Shrotri N. Undergraduate urology in the UK: Does it prepare doctors adequately? British Journal of Medical and Surgical Urology. 2012;5:20-7.

10. Loughlin KR. The current status of medical student urological education in the United States. J Urol. 2008;179:1087-90.

11. Sullivan JF, Forde JC, Thomas AZ, Creagh TA. Avoidable iatrogenic complications of male catheterisation and inadequate intern training: a 4-year follow-up post implementation of an intern training program. Surgeon. 2015 Feb;13(1):15-8

12. Zeldow PB, Preston RC, Daugherty SR. The decision to enter a medical speciality: timing and stability. Med Educ. 1992 Jul;26(4):327-32

13. Khader Y, Al-Zoubi D, Amarin Z, Alkafagei A, Khasawneh M, Burgan S, El Salem J, Omari M. Factors affecting medical students in formulating their speciality preferences in Jordan. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:32.

14. Harris MG, Gavel, PH, Young JR. Factors influencing the choice of speciality of Australian medical graduates. Med J Aust. 2005 Sep 19;183(6):295-300.

15. O’Herrin JK, Lewis BJ, Rikkers LF, Chen H. Why do students choose careers in surgery? J Surg Res. 2004 Jun 15;119(2):124-9

16. Sternszus R, Cruess S, Cruess R, Young M, Steinert Y. Residents as role models: impact on undergraduate trainees. Acad Med. 2012 Sep;87(9):1282-7

17. Bongiovanni T, Yeo H, Sosa JA, Yoo PS, Long T, Rosenthal M, Berg D, Curry L, Nunez-Smith M. Attrition from surgical residency training: perspectives from those who left. Am J Surg. 2015 Oct;210(4):648-54

18. Goldacre MJ, Goldacre R, Lambert TW. Doctors who considered but did not pursue soecific clinical specialities as careers: questionaaire surveys. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(4):166-176

19. Markert RJ, Rodenhauser P, El-Baghdadi MM, Juskaite K, Hillel AT, Maron BA. Personality as a prognostic factor for specialitry choice: a prospective study of 4 medical school classes. Medscape J Med. 2008;10(2):49

20. Cleland J, Johnston PW, French FH, Needham G. Associations between medical school and career preferences in Year 1 medical students in Scotland. Med Educ. 2012;46(5):473-484

21. Morrison J. Career preferences in medicine for the 21st century. Med Educ. 2006;40:495-497

22. Heiligers PJ. Gender differences in medical students’ motives and career choice. BMC Med Educ. 2012 Aug 23;12:82

23. Bernstein J, Dicaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2335-8

24. Hill JF, Yule A, Zurakowski D, Day CS. Residents' perceptions of sex diversity in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Oct 2;95(19):e1441-6

25. Templeton K, Wood VJ, Haynes R. Women and minorities in orthopaedic residency programs. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15 Suppl 1:S37-41.

(P648)