An Audit of Paediatric Organ and Tissue Donation in Ireland

L. Marshall1, I. Hennessey2, C. Lynch3, C. Gibbons2, S. Crowe1,4

1. Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care Medicine, Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital Crumlin, Dublin.

2. Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care Medicine, Temple Street Children’s University Hospital, Dublin.

3. Organ Donation and Transplant Ireland, Hardwicke Place, Temple Place, Dublin.

4. Department of Paediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Dublin, Trinity College, Dublin.

Abstract

Aim

Our aim was to present an overview of patterns of paediatric organ donation in the Republic of Ireland from January 2007 to January 2018.

Methods

We performed a retrospective audit of organ donation practice in paediatric intensive care units (PICU) in Ireland.

Results

Thirty-six children donated organs or tissue heart valves over the 11-year period. There were 13 paediatric organ donors between 2007 and 2012, this increased to 23 paediatric organ donors between 2013 and 2017. 2017 had the highest number of organ donors at 9

Conclusion

Organ donation in Irish PICUs has increased over the last 11 years due to a combination of factors: improved resourcing and organization of Organ Donation Transplantation Ireland (ODTI), the establishment of clinical leads (both medical and nursing) in organ donation, a heightened awareness of organ donation and improved specialist Intensive Care dedicated consultant staffing. Finally organ donation is possible only through the generosity and altruism of bereaved families. Outcomes from donated organs have been excellent throughout the 11 year period audited.

Introduction

Organ donation may be considered in children who die in paediatric intensive care units if certain criteria are met and if their families wish for organ donation. In general organs are donated after death has been confirmed using neurological criteria to diagnose brainstem death (BSD). Donation of organs can also occur in certain circumstances after death has been confirmed using circulatory criteria (DCD). The Intensive Care Society of Ireland has published guidelines on organ donation after brainstem death and more recently on donation after circulatory death1,2. The American College of Critical Care Medicine, The Academy of Royal Medical Colleges and The Australian & New Zealand Intensive Care Society have all also published specific guidelines on the determination of brainstem death in infants and children3,4,5.

Paediatric renal transplantation is carried out in Temple Street University Hospital. All other solid organ paediatric transplantations are carried out in the United Kingdom (UK), in specialist centers where numbers are sufficient to maintain a transplant programme. Ireland currently shares organs donated with the UK as part of this arrangement. We examined all cases of organ and tissue donation from the paediatric critical care units in the Republic of Ireland over an 11-yer period from January 2007 through to January 2018. Outcome data was obtained for the majority of organs transplanted.

Methods

This is a retrospective audit of organ donation practice in PICU’s in Ireland. Information was extracted from clinical case notes, electronic clinical information system and the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANet) which all paediatric critical care units in Ireland and the UK contribute to6. The Office for Organ Donation and Transplant Ireland (ODTI) obtained outcome data on individual transplanted organs from transplanting centers in the UK. A waiver was obtained from the hospital ethics committee, as this was an audit of current practice. All data was anonymized and confidentiality protected due to the sensitive nature of traumatic death and donation.

Results

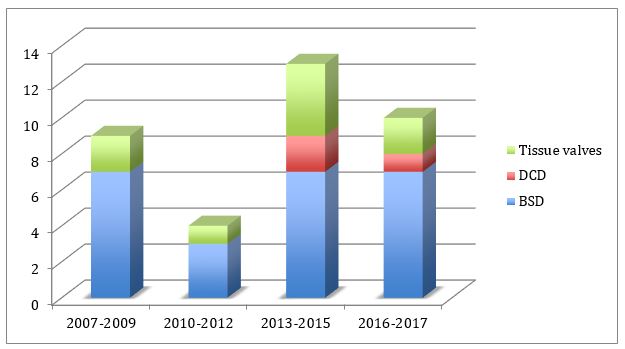

Thirty-six children donated organs or heart tissue heart valves over an 11-year period. Donation rates increased over the last five years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Yearly trend of organ donation rates

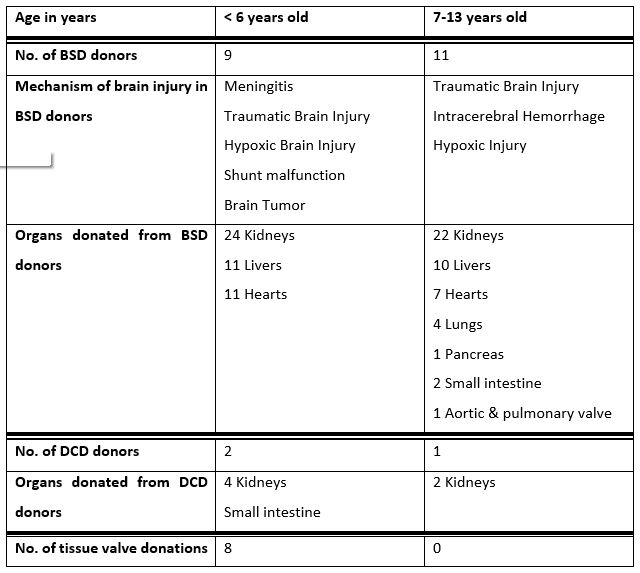

Nine patients donated heart valve tissues and 27 patients donated solid organs. 24 of the 27 (89%) solid organ donors donated after brainstem death and the remaining 3 (11%) donated after circulatory death. The most frequent cause of death in children and infants who donated solid organs was traumatic brain injury (33%) resulting in brainstem death. This was followed by meningoencephalitis (22%), intracerebral haemorrhage (15%) and hypoxic brain injury (7%) (Table 1).

Table 1: Overview of organ & tissue valve donor demographics & mechanism of injury

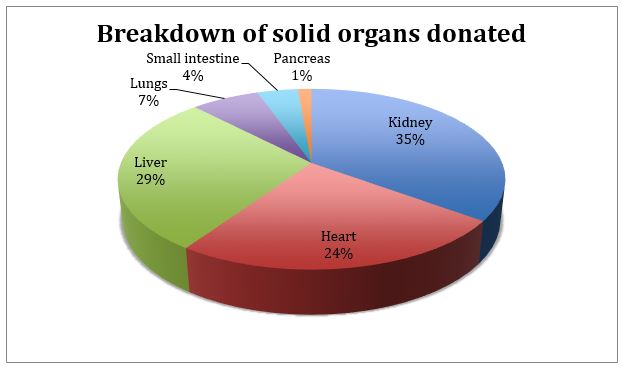

The most frequently donated organs were kidneys followed by liver and heart (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Breakdown of solid organs donated

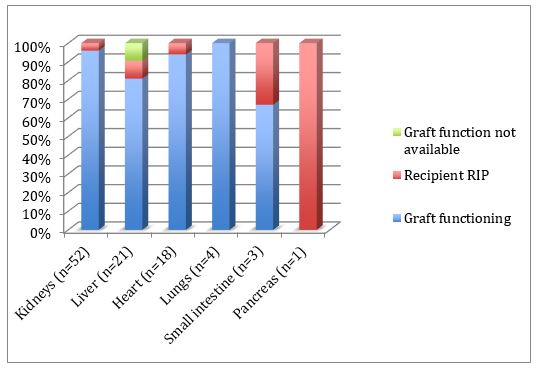

Outcome information on the survival of grafted organs was available for the majority of donated organs. In total 52 kidneys were donated and one year survival rate of donor grafts was 96%. One year survival rate of donor hearts and donor livers was 94% and 81% respectively (Figure 3). There was no outcome data available for tissue heart valve recipients.

Figure 3: Graft function of donated organs

Discussion

Over the last 11 years organ donation rates have increased in Irish PICUs. The reason for this is multifactorial. Allocation of resources to the ODTI have improved, specific education sessions on organ donation for staff now occur, consultant staffing in PICUs has improved and awareness of organ donation among consultants has increased and finally there is an increased awareness among the public of the need for organ donation and transplantation as a result of advocacy groups and the support of the media. Several organizations in Ireland have been active in the area of public awareness, especially the Irish Kidney Association. There is some evidence that discussion in the media may influence parental decisions to donate7.

In the 11-year period examined, 36 infants and children ranging in age from one day of life to 15 years of age donated organs and/or tissue heart valves for transplantation. This represents a donation rate of 2.9 per million population of children. In the US donation rates are 1.2 per million population of children8. Patients were admitted to the PICU in Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital Crumlin (OLCHC) and the Children’s University Hospital Temple Street (CUHTS), where there are a combined total of 30 operational beds. Surgical retrievals of organs and tissue heart valves were performed in each hospital. During the period examined there were more than 700 deaths in PICU. Almost 60% of these occur following limitation of active treatment and re-direction of care, in keeping with international paediatric critical care practice. The numbers of children and infants referred to donate tissue or organs is small in proportion to the total number of deaths.

Within the last five years DCD, as opposed to donation after BSD, has occurred in both paediatric centers and its acceptance has slowly increased in the paediatric medical community. DCD can be considered in a child who is expected to die shortly after withdrawal of life sustaining treatment in the PICU. Given the increasing gap between the number of organs required for transplantation and the number available, this is a category that could potentially be expanded to increase the overall number of paediatric donors over the next decade. Two of the most frequently demanded organs in children are kidneys and liver9. Organs that can be donated after DCD include kidneys, liver, lungs and small bowel. Survival rates of recipients of organs from DCD donors are comparable to recipients of organs from BSD donors10,1112.

Care of the donor patient after brainstem death is an important aspect of optimizing graft function and fulfilling the wishes of the child’s family. Meticulous management of fluid, electrolyte, cardiovascular and respiratory support may improve graft function in the recipient13,14. In addition to physiological and pharmacological support of the donor, psychological, spiritual and bereavement support must be provided for the deceased’s parents and family7. Families are being asked to make an important and difficult decision under the most traumatic and upsetting circumstances. Critical care staff must be able to provide emotional support and empathy, with understandable information on organ donation. Consent to donation is associated with high levels of emotional support from staff15. Some data has suggested that organ donation can help families during the bereavement process16. This focused area of critical care medicine is targeted to the individual needs of the paediatric donor and their family. Both PICUs in Ireland have dedicated full-time intensive care consultants and nurses who are trained in the management of potential organ donors and their families.

Ireland shares a paediatric transplantation service with the UK for heart, liver and lung transplantation. Therefore data regarding organs transplanted and success rates is more difficult to obtain. These services are accessed across a number of specialist centres in London and Newcastle. Renal transplantation in children greater than 10kg is performed in Ireland. Infants who require a kidney transplant and who weigh less than 10kg are managed with peritoneal dialysis, or may be referred to the UK. The ODTI contacted the UK on our behalf to obtain follow-up information on the survival of grafted organs (Figure 3). Outcome information was available for 25 of the 27 solid organs donated. One year survival of donor grafts was over 80% for kidneys, liver, heart and lungs. There is no outcome data available for heart valve recipients.

This audit demonstrates that whilst the numbers of paediatric organ donations in Ireland are small, they have increased over the last 10 years. Challenges of paediatric organ donation include difficulties encountered with smaller graft sizes, more challenging surgical anastomosis, difficulty in size matching recipients with donated organs and a higher incidence of graft dysfunction compared to the adult population. Public awareness and support of the need for organ donation in children is essential for the continued growth of a paediatric organ donation program. The introduction of DCD may potentially increase organ donation rates further in the future. Consent to organ donation and the meaning associated with the act of organ donation may help bereaved families17. Survival rates for recipients of organs in our audit are excellent. Improvement in tissue preservation methods has led to improved outcomes. The use of hypothermic machine perfusion in kidney transplantation, normothermic perfusion of lungs for assessment and treatment (Ex-Vivo Lung perfusion), and normothermic perfusion of hearts is now a viable and increasingly accepted method of preservation. Machine perfusion whether for livers (Organ Ox Metra), Hearts (Transmedics) or lungs (Transmedics) has the potential to extend the maximum acceptable periods of ischemic times, ameliorate the effects of periods of warm ischemia and provide an environment where organs may be viewed producing urine, bile or pumping blood and generating pressure volume curves where hearts are concerned. Critical care staff play a crucial role in the management of organ donors and their families and recognition of this role also has the potential to improve organ donation numbers and outcomes.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Suzanne Crowe

Consultant Paediatric Intensivist,

Paediatric Critical Care Unit,

Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital,

Crumlin,

Dublin.

Email: [email protected]

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have a conflict of interest with this retrospective audit.

Funding Statement

Funding for this study was obtained from institutional sources only.

Contribution Statement

Drs. Marshall and Hennessey collected the audit data. Ms. Lynch collected the outcome data. Dr. Marshall, Gibbons and Crowe prepared the manuscript. All five authors have read and approved the content.

References

1. Dwyer R, Motherway C, Phelan D. Diagnosis of Brain Death in adults;Guidelines Intensive Care Society of Ireland; 2016 Oct 29;:1–10.Available from https://www.jficmi.ie/standards-documents/icsi-guidelines-on-brainstem-death-and-management-of-the-organ-donor/

2. J O, Dwyer R, Marsh B. Donation after Circulatory Death Guidelines; Intensive Care Society of Ireland: 2017 May 30;1–21. Available from Available from https://www.jficmi.ie/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DCD-ICSI-Guideline.pdf

3. Nakagawa TA, Ashwal S, Mathur M, Mysore M, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Section on Critical Care and Section on Neurology of American Academy of Pediatrics, Child Neurology Society. Clinical report—Guidelines for the determination of brain death in infants and children: an update of the 1987 task force recommendations. Vol. 128, American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011. pp. e720–40.

4. A code of practice for the diagnosis and confirmation of death. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges; 2008 Oct 4;1–42. Available form http://aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Code_Practice_Confirmation_Diagnosis_Death_1008-4.pdf

5. The ANZICS statement on death and organ donation. 2017 Apr 13;:1–68. Available from http://www.anzics.com.au/death-and-organ-donation/

6. Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANeT) [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. pp. 1–1. Available from: http://www.picanet.org.uk/

7. Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. Pediatric Organ Donation: What Factors Most Influence Parents’ Donation Decisions? Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. NIH Public Access; 2008 Mar 1;9(2):180–5.

8. Organ Procurment and Transplantation Network. US Department of Health and Human Services [Internet]. pp. 1–1. [Cited April 2018] Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/

9. Committee on Hospital Care, Section on Surgery, and Section on Critical Care. Policy statement--pediatric organ donation and transplantation. Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2010 Apr;125(4):822–8.

10. Weber M, Dindo D, Demartines N, Ambühl PM, Clavien PA. Kidney transplantation from donors without a heartbeat. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jul;347(22):1799-801.

11. D'Alessandro AM, Fernandez LA, Chin LT, Shames BD, Turgeon NA, Scott DL, Di Carlo A, Becker Y, Odorico Js, Knechtle SJ, Love RB, Pirsch JD, Becker BN, Musat AI, Kalayoglu M, Sollinger HW. Donation after cardiac death: the University of Wisconsin experience. Ann Transplant. 2004;9(1):68-71.

12. Inci I, Hillinger S, Schneiter D, Opitz I, Schuurmans M, Benden C, Weder W. Lung Transplantation with Controlled Donation after Circulatory Death Donors. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. The Editorial Committee of Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery; 2018 Jul :1-7.

13. Rosendale JD, Kauffman HM, Mcbride MA, Chabalewski FL, Zaroff JG, Garrity ER, Delmonico FL, Rosengard BR. Aggressive Pharmacological Donor Management Results In More Transplanted Organs. Transplantation. 2003 Feb;75(4):482-7

14. Mascia L, Mastromauro I, Viberti S, Minerva MV, Zanello M. Management to optimize organ procurement in brain dead donors. MinervaAnestesiologica. 75(3):125–33.

15. Jacoby L, Jaccard J. Perceived Support Among Families Deciding About Organ Donation for Their Loved Ones: Donor Vs Nondonor Next Of Kin. Am J Crit Care. American Association of Critical Care Nurses; 2010 Sep 1;19(5):52–61.

16. Merchant SJ, Yoshida EM, Lee TK, Richardson P, Karlsbjerg KM, Cheung E. Exploring the psychological effects of deceased organ donation on the families of the organ donors. Clin Transplant. 2008 May;22(3):341-7.

17. Finlay I, Dallimore D. Your child is dead. BMJ. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 1991 Jun 22;302(6791):1524–5.

P840