Cannabis Oil in an Irish Children’s Critical Care Unit

P. Fennessy, L. Murphy, S. Crowe

Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia, Critical Care Medicine and Pain Medicine, Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin 12.

Abstract

Aims

We present a case of a five-year-old female admitted postoperatively to the Paediatric Critical Care Unit with a history of refractory seizures for which her parents were administering cannabis oil.

Methods

We discuss the issues surrounding cannabis prescription in Ireland and the role of parental autonomy in medication selection and administration.

Results

An administration regime was agreed upon following discussion with the child’s parents.

Conslusion

While this case raised ethical and legal issues, we must also consider parental autonomy and their role as advocate for their child during admission to critical care.

Introduction

Cannabis is derived from the Cannabis sativa plant. There is considerable public interest in the use of cannabinoid derivatives to treat a multitude of medical conditions. Although there have been many anecdotal reports on the effectiveness of cannabis for medicinal use, there is a paucity of robust scientific data demonstrating the efficacy of cannabis products as a therapy. This data is a mandatory requirement for any regulatory body that is charged with assuring the safety, efficacy and quality of authorised medicines.

Case Report

We present a case of a five-year-old female admitted postoperatively to the Paediatric Critical Care Unit (PCCU). She had a history of refractory seizures. Her parents had obtained cannabis oil from the United States and were administering it to her at night, in addition to her regular anticonvulsant medication. Her parents reported decreased seizure frequency since its commencement. The child had elective tonsillectomy for management of significant obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), possibly exacerbated by the sedative properties of cannabis. The admitting surgical and critical care teams were unaware that the child was regularly receiving cannabis until 14 hours after admission to hospital. The PCCU and the hospital do not currently have any guidelines to assist medical and nursing staff with the safe use of this potentially psychogenic preparation. The Irish Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) published a scientific review on the subject in January 20171. After discussion with the child’s parents, we agreed an administration regimen, the timing of which was separate to regular sedative medication in view of the child’s history of OSA. The child’s postoperative course and stay in PCCU was uncomplicated.

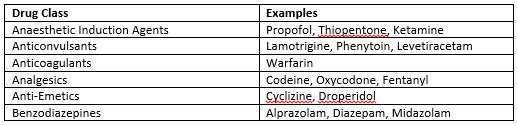

Table 1: Potential Drug Interactions6

Discussion

Cannabis is considered to be a narcotic substance under the 1961 UN Convention on Narcotic Drugs. There are several different constituents of cannabis including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which has psychoactive and psychogenic effects. Cannabidiol (CBD) is a non-psychogenic constituent. The HPRA have advised that if treatment with cannabis for medical purposes becomes policy it should only be available through a controlled access programme for just 3 patient groups: those with resistant spasticity secondary to multiple sclerosis, chemotherapy-induced intractable nausea and patients with refractory epilepsy. Chronic pain was not included in this recommendation.

Currently in Ireland, cannabis preparations that are psychogenic are controlled under the Misuse of Drugs legislation and are therefore not permitted for medical use. This is due to insufficient evidence demonstrating clinical benefit. In 2016 the Cannabis for Medicinal Use Regulation Bill passed the first stage in Dáil Éireann2. There is the potential for drug interactions as THC and CBD are both metabolised via the cytochrome P450 system3. Interactions of particular interest to PCCU and paediatric anaesthesia relate to sedative effects (Table 1).

The use of complimentary and alternative medicine (CAM) has grown in popularity over the last 2 decades4. As clinicians we need to be aware that parents may be using CAM therapies to treat their children and be prepared to discuss these options openly with parents in the PCCU5. In this case the child was receiving Charlotte’s Web hemp oil, which is high in CBD and low in THC concentrate (Fig 1). Although CBD is not subject to the Misuse of Drugs legislation, THC is. In a case such as this, clinicians should consider contacting the HPRA, and seek legal and pharmacist advice within their hospital. Consideration should also be given to separate consent forms permitting the administration of unlicensed medications.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have a conflict of interest with the issues raised in this paper.

Funding Statement

No funds external to our department were sought or obtained for the preparation of this paper.

Contributorship Statement

The idea and initial drafting of the manuscript was carried out by all three authors equally. Dr. Fennessy completed the paper, and it was revised by Drs. Fennessy and Crowe.

Correspondence:

Dr. Suzanne Crowe,

Consultant Paediatric Intensivist,

Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital,

Crumlin, D12.

E-mail: [email protected]

Tel: 0868328930

References

1. O’Mahony D. Cannabis for Medical Use - A Scientific Review. 2017 Jan: 1-83.

2. An Bille um Rialáil Cannabais atá lena Úsáid chun críocha Íocshláinte, 2016 Cannabis for Medicinal Use Regulation Bill 2016. 2016 Jul: 1-28.

3. Stout SM, Cimino NM. Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review. Drug Metab Rev. 2014; 46(1): 86-95.

4. Pitetti R, Singh S, Hornyak D, Garcia SE, Herr S. Complementary and alternative medicine use in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001 Jun; 17(3): 165.

5. Zuzak TJ, Zuzak-Siegrist I, Simões-Wüst AP, Rist L, Staubli G. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients presenting to a paediatric Emergency Department. Eur J Pediatr. 2009; 168(4): 431-7.

6. https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/cannabis-index.html

P807