Caring for Obese Children- A change in Paradigm.

Doyle S.1,2, Cahill D.2, Smyth M.2, Murphy S.1,2

The Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street, Dublin 1.1

Faculty Of Paediatrics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4.2

Abstract

Childhood Obesity is a problem of epidemic proportions. The causes are complex and treatment results are variable with much research ongoing. We analysed the initial assessment forms of a group of patients attending the W82GO! Healthy Lifestyle service at The Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street to look at the population and their specific needs. Our analysis revealed a high proportion of emotional and behavioural problems along with bullying. This group of patients are complex and a multi-disciplinary team approach is essential in their treatment.

Introduction

Obesity one of the top three social economic burdens generated by human beings and has been highlighted as a major public health concern1. In the Irish population, obesity spans all social classes and affects four out of five adults over fifty2. In the paediatric population 7% of Irish children aged nine are obese and 19% are overweight3. The economic burden of caring for obese adults has been projected to be 5.4 billion euro by 20304. Overweight children are at significantly increased risk of becoming obese adults when compared with non-obese/overweight children5. Extensive research in the area of obesity management proves that the old adage of ‘energy in= energy out’ does not represent the complexity of the issue 6-9. Well documented complications of obesity include: low physical fitness, hypertension, early signs of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome10-13 mental health and well-being is adversely affected. Furthermore, children with obesity are frequently subjected to teasing, bullying, discrimination and other forms of social marginalisation which are associated with lower self-esteem, depression, adverse social functioning as well as lower academic achievement14. The objective of this study was to describe the children at the commencement of obesity treatment in relation to emotional health, behavioural difficulties, learning difficulties and bullying.

Methods

We reviewed the initial assessment of 111 children who attended our service. Our aim was to describe some of the characteristics of the group referred to our clinic. At the first visit each child has an assessment form completed by a member of the Multi- disciplinary team. The form consists of questions relating to physical activity, eating behaviour, sedentary lifestyle, emotional health and wellbeing as well as other information from the medical history. Full ethical approval was granted by the Ethics department at The Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street.

Results

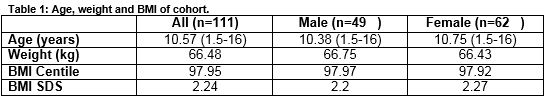

Five percent (6/111) of the children were under 5. Ninety-five percent (105/111) were over 5. The average age at initial consultation was 10.57 years.

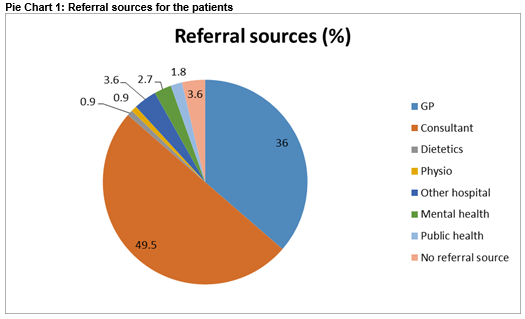

The majority of our referrals (49.5%, 50/111) come from consultants based in Temple Street, GP referral accounts for 36%(40/111) of referrals and the remaining 14.5% are from other hospitals, public health agencies and allied health professionals in the community.

A detailed history is taken from each child and their parents, but for this paper self-reported emotional difficulties, behavioural difficulties and learning difficulties will be discussed.

At initial screening, 33% disclosed emotional difficulties and 46% of whom were linked to mental health services prior to commencing the programme. Of the emotional difficulties which the children described low mood, deliberate self-harm and low self-esteem are examples. The 54% who described emotional difficulties were all seen by the psychologist on the team, and in some instances, were referred on to local Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services for ongoing treatment.

Behavioural difficulties feature in this cohort also with 26% of those assessed reporting difficulties. Often the parents disclose this information on behalf of the child. Fifty-two percent of those with behavioural difficulties were already attending mental health services in the form of counselling or Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Thirty percent of the parents reported their children as having learning difficulties and 15% reported developmental delay at some point requiring some intervention. The degree of delay varied but speech delay and Autistic Spectrum disorder made up a large proportion of the difficulties. Sixty-three percent of the children reported being teased about their weight in the past with 12% missing days from school as a result of bullying. Almost half of those teased were teased by their peers although a small percentage (2%) were teased by strangers.

Discussion

Childhood obesity represents the largest public health concern of this generation. The physical and psychological complications are well reported. Failure to adopt a healthier lifestyle and reduce body mass index results in increased health problems, psychological problems and increased projected healthcare expenditure. This retrospective review highlights the difficulties faced in treating these children as they have psychological difficulties which can affect their progress thus making them a more demanding cohort of patients. Emotional health represents a significant issue within the cohort of patients attending for an initial assessment with less than half of those affected attending mental health services. Worryingly, these figures are in contrast to the data collected by The Growing Up In (GUI) Ireland in 2011, which shows that the majority of children analysed were developing without emotional problems. This study represents a cross sectional cohort of 9-year-old children. The research showed that 15-20% of the children surveyed were in difficulty. This figure is based on mother and teacher reports3.

This study highlights the high incidence of emotional difficulties in this cohort when compared to the general population. It also highlights a demand on resources when treating these children. The Growing Up In Ireland data highlighted that children from lower income families had more problems of an emotional or behavioural nature. This is felt to be related to the quality of parent-child relationship and not solely income. Income was not assessed in our study and this represents an area for analysis in the future. The incidence of behavioural problems within our group is significant. Twenty-six percent of the children reviewed disclose behavioural problems with only 52% of these in receipt of help. The treatment offered is a group outpatient family based healthy lifestyle programme which is unsuitable for some of these children who have problems in a group setting. Moreover, 48% of the families attending the service are dealing with these behavioural issues without professional help. The psychologist on the team assesses all children and provides support until other services are put in place.

The incidence of learning difficulties as reported by the parents was 30%. Fifteen percent received intervention at some stage. Comparison with the general population is difficult as there is a paucity of data on this. In part, this is related to the wide range of severity of learning difficulty. The National Council for Special Education study on the prevalence of Special Needs Education estimated prevalence rates of 23% in 201115. This is different to other national estimates of learning difficulty, therefore comparison with our group is not possible. Bullying represents a very big issue within our group. The social stigma attached to obesity clearly plays a big role and indeed this is a barrier to treating obesity. The effects of bullying are low self-esteem, absenteeism and low mood. The result can be social isolation and difficulties mixing with peers during sports and other activities. Our group showed a high incidence of absenteeism as a direct result of bullying.

This paper highlights the complexity of caring for children with obesity as a result of their emotional, behavioural and learning difficulties. Left untreated, the health consequences of obesity are severe, therefore a multi- disciplinary team approach is needed. This must include a psychologist and all members of the team must be mindful of the complex issues these children have. Moreover, given the increasing prevalence of childhood obesity, all professionals working with children must consider the psychological difficulties these children have and their potential effect on treatment. While this review highlights the complexity of this group, it looks at only parent reporting as part of an initial assessment. Further analysis of psychological health, by analysis of teacher and more in-depth parental questioning is required. Moreover, further research is needed to analyse the effect treatment has on the psychological well-being of these children.

Conflict of Interests

All authors declare no conflict of Interest.

Correspondence:

Dr Samantha Doyle, Special Lecturer In Paediatrics, UCD, St. George’s Hall, The Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street, Dublin 1.

E-mail: [email protected]

References:

1. Dobbs Richard SC, Thompson Fraser, Manyiks James. Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis. Mc Kinsey Global Institute: 2014.

2. Leahy S, Nolan, A., O' Connell J., Kenny, RA. Obesity in an geing Society: Implications for health, physical function and health service utilisation. 2014.

3. Willams J GS, Doyle E, Harris E, Layte R The Growing Up In Ireland National Longitudinal Study of Children- The Lives of 9 year olds. In: ESRI, editor. 2011.

4. Keaver L, Webber L, Dee A, Shiely F, Marsh T, Balanda K, Perry IJ. Application of the UK foresight obesity model in Ireland: the health and economic consequences of projected obesity trends in Ireland. 2013.

5. Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, Van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obesity reviews. 2008;9:474-88.

6. Reilly JJ, Kelly L, Montgomery C, Williamson A, Fisher A, McColl JH, Lo Conte R, Paton JY, Grant S. Physical activity to prevent obesity in young children: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2006;333:1041.

7. Gately PJ, Cooke CB, Barth JH, Bewick BM, Radley D, Hill AJ. Children's residential weight-loss programs can work: a prospective cohort study of short-term outcomes for overweight and obese children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:73-7.

8. Reinehr T, Temmesfeld M, Kersting M, De Sousa G, Toschke A. Four-year follow-up of children and adolescents participating in an obesity intervention program. International journal of obesity. 2007;31:1074-7.

9. Wake M, Lycett K, Clifford SA, Sabin MA, Gunn J, Gibbons K, Hutton C, Mc Callum Z, Arnup SJ, Wittert G. Shared care obesity management in 3-10 year old children: 12 month outcomes of HopSCOTCH randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346:f3092.

10. O’Malley G, Santoro N, Northrup V, D’Adamo E, Shaw M, Eldrich S, Caprio S. High normal fasting glucose level in obese youth: a marker for insulin resistance and beta cell dysregulation. Diabetologia. 2010;53(6):1199-209.

11.D'Adamo E, Cali AM, Weiss R, Santoro N, Pierpont B, Northrup V, Caprio S. Central role of fatty liver in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in obese adolescents. Diabetes care. 2010;33(8):1817-22.

12.Finucane F, Pittock S, Fallon M, Hatunic M, Ong K, Burns N, Costigan C, Murphy N, Nolan JJ. Elevated blood pressure in overweight and obese Irish children. Irish journal of medical science. 2008;177(4):379-81.

13.Tounian P, Aggoun Y, Dubern B, Varille V, Guy-Grand B, Sidi D, Girardet JP, Bonnet D. Presence of increased stiffness of the common carotid artery and endothelial dysfunction in severely obese children: a prospective study. The Lancet. 2001;358(9291):1400-4.

14.Thamotharan S, Lange K, Zale EL, Huffhines L, Fields S. The role of impulsivity in pediatric obesity and weight status: a meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33(2):253-62.

15.Banks J, McCoy S. A study on the prevalence of special educational needs. Dublin: NCSE. 2011.

(P543)