Coming of Age in Ireland: the Twilight Zone!

B.D. Power1, P. Stewart1, G. Stone1, P. O’Reilly1, C. Costigan1, C. O’Gorman1,2, A.M. Murphy1,2

1. Department of Paediatrics, University Hospital Limerick, Ireland

2. Department of Paediatrics, Graduate Entry Medical School, University of Limerick

Abstract

Aim

To describe the healthcare needs of adolescent patients inhabiting the ‘seventh age of childhood’ in our region with a view towards future workforce and infrastructure planning.

Methods

This is a retrospective descriptive study of patients aged between 14 and 16 years presenting to each of the six hospitals in our hospital group over a 10 year period (01.07.2006-1.07.2016) using electronic databases.

Results

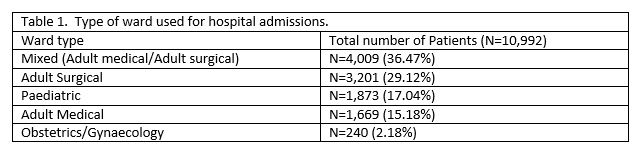

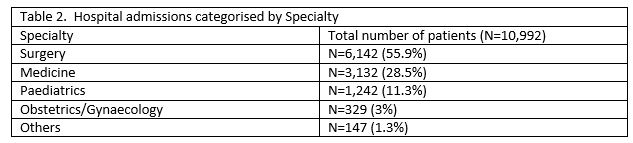

There were 10,992 hospital admissions, 41,456 outpatient appointments and an average of 1,847 attendances per year at our Emergency Department in this age group. Seventeen percent (n=1,873) of patients were admitted to age appropriate wards. Only 11.3% (n=1,242) of our cohort were admitted under the care of a Paediatrician.

Conclusion

The Irish healthcare agenda needs to be advanced to ensure the optimal health for this valuable, yet vulnerable generation. Further investment will help shape the fledgling discipline of ‘adolescent health’ in Ireland.

Introduction

‘The imagination of a boy is healthy, and the mature imagination of a man is healthy; but there is a space of life between, in which the soul is in ferment, the character undecided, the way of life uncertain, the ambition thick-sighted: thence proceeds mawkishness.’

John Keats (1795-1821)

Adolescence is a dynamic transitional period of physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural development that can bring curiosity, innovation and opportunity, but also angst and upheaval. ‘Coming of age’ presents a myriad of challenges to the modern Irish teenager, and often to the healthcare professionals tasked with their care. The 2016 Government of Ireland Census reports that there are now 404,540 people between the ages 12 and 18 years living in the Republic of Ireland. Of these, 173,146 inhabit that twilight zone of 14-16 years of age.[i] This ‘Seventh age of Childhood’ is the least understood, least researched and therefore least resourced of all developmental ages.

The era of ‘Snapchat’ and ‘Instagram’, ‘Sexting’ and ‘Tinder’, has led to an unprecedented cultural change for ‘Generation Z’. This ubiquitous presence of social media in the lives of Irish adolescents has amplified age-old peer pressures. Ireland has the 4th highest suicide rate in Europe amongst adolescents [ii], and a significantly higher rate of bullying than our European counterparts.[iii] These are stark and powerful reminders that further investment in adolescent health and wellbeing is urgently required to support our youth in navigating the arduous path between adolescence and adulthood.

As maturation does not always correspond directly to chronological age, the parameters of adolescence are difficult to define. The age at which a patient is deemed ‘child’ versus ‘adult’ has varied between institutions in Ireland. A national mandate in 2017, outlined in the National Model of Care for Paediatric & Neonatology and Emergency Medicine has standardised the age cut-off for paediatric patients attending Emergency Departments. This mandate dictates that all patients have their medical care overseen by a Paediatrician up to the eve of their 16th birthday. The age cut off point for children with mental health problems remains at 18 years in line with mental health legislation (Mental Health Act, 2001).

The UL Hospital group is comprised of six clinical sites – University Hospital Limerick, University Maternity Hospital, Croom Orthopaedic Hospital, Ennis Hospital, Nenagh Hospital and St. John’s Hospital. These hospitals provide acute care for the population of Limerick, Clare, North Tipperary and surrounding counties. Within this context, we aim to highlight the healthcare needs of the adolescent population over the past 10 years in this regional hospital group with a view towards future workforce and infrastructure planning.

Methods

This is a retrospective descriptive study of patients aged between 14 and 16 years presenting to each of the six hospitals in our hospital group over a 10 year period (01.07.2006-1.07.2016). Electronic databases were used to examine details of adolescent hospitalisations, outpatient consultations and emergency department presentations. Patient databases were used to collate data including demographics, diagnoses, duration of hospitalisation, type of inpatient ward, speciality of admitting Consultant and clinic attendances. Patient data was recorded on a password-encrypted database on Microsoft Excel and analysed using descriptive statistics.

Results

10,992 hospital admissions (median: 1101 admissions per year; range: 595-1207) and 41,456 outpatient appointments (median: 3768 appointments per year; range: 1924-4838) were included for this cohort over the 10 year study period. There were a total of 5,539 Emergency Department (ED) presentations over a three year period (01.01.2014-31.12.2016) (median: 1723 presentations per year; range 1721-2095).

Of these 10,992 hospital admissions, 7,880 patients were admitted to the University Hospital Limerick, 951 patients to Nenagh Hospital, 949 patients to Ennis hospital, 593 patients to St. Johns Hospital, 379 patients to Croom Orthopaedic Hospital and 240 patients to the University Maternity Hospital.

The total number of inpatient days was 23,979 days (equivalent to 65.69 years). The average length of in-patient stay was 2.1 days (range 1-96 days). 6.5 beds were used per day, on average for this cohort.

The top 5 reasons necessitating admission in this age group (in decreasing order of frequency) were abdominal pain ( of which 17% were diagnosed as appendicitis), injuries, tonsillitis, headache (of which 16% were diagnosed as migraine) and maxillofacial issues.

Of the 41 456 outpatient contacts, 7,828 (19%) were reviewed by a Paediatrician. 33,628 patients were reviewed by other specialties. Of these 25 other specialties available in this hospital group, the most prevalent in order of frequency were Orthopaedic surgery (n=14,057 33.9%), Otolaryngology (n=3962, 9.5%), Maxillofacial Surgery (n=3007, 7.2%), Dermatology (n=3035, 7.3%) and ophthalmology (n=2522, 6%).

Discussion

The hospital group evaluated in this study encompasses 6 hospital sites, catering for a catchment area of 100,000 individuals less than 18 years of age with 18,387 of these estimated to be in the 14-16 year age group. This study has provided a representative view of the healthcare requirements of Irish youths in this demographic area over the past decade. To date, this has been the first study in Ireland to describe the hospitalisation of Irish adolescents. This novel data describes the diverse needs of this patient cohort and illustrates the variety of disciplines required to provide healthcare to Irish adolescents.

Acknowledgement of the necessity for change in adolescent healthcare dates back to 1959 with the publication of the Platt report.[iv] This report recommends that adolescents be cared for separately from adult and paediatric wards. Dodds’ review of the literature [v] identifies privacy, independence and psychological support as three fundamental requirements to achieve positive healthcare experiences for young people. Viner [vi] illustrates that adolescents are more likely to report excellent overall care, feeling secure, having confidentiality maintained, feeling treated with respect, confidence in staff, appropriate information transmission, appropriate involvement in own care, and appropriate leisure facilities if cared for in an adolescent ward compared to an adult ward. This validates the role of designated adolescent units. Menzies-Lyth [vii] and Busen [viii] outline developmental regression as a potential and natural reaction to stressful situations for adolescents during hospitalisation. Therefore, in the absence of the availability of specific adolescent units, it is acknowledged that paediatric wards are preferable to adult wards.

Undoubted deficiencies in the provision of an optimum hospital setting for adolescents were highlighted in our study. Of note, less than one fifth of patients were admitted to an age-appropriate ward, and only 11% of patients were cared for by a Paediatrician during their inpatient stay. These striking statistics highlight the scarcity of dedicated resources currently available to effectively meet the healthcare needs of this special population and demonstrate a pressing need for further investment in this area.

The unique challenges of providing adolescent-focused healthcare in Ireland cannot be underestimated, and differ distinctly from those of children and adults. To meet these challenges adolescent medicine has emerged as a subspecialty from paediatric and adult medicine, however to date no such specialist has been appointed in Ireland. Building an effective workforce of highly-skilled adolescent health professionals who understand the specific biological, psychological, behavioural, social, and environmental factors that impact the health of adolescents is critical to engage youths in healthcare and address complex psychosocial needs that may otherwise go unnoticed.

Despite considerable advances in the survival and health of young children in high-income and middle-income countries, equivalent indicators in adolescents have remained the same for decades.[ix] The current momentum to prioritize adolescent medicine training around the globe is reflected by the creation of adolescent inpatient units and numerous advanced training opportunities in established programs in Australia, the United States, and Canada in particular.[x] In addition, there have been several initiatives to incorporate adolescent health training in undergraduate medical education in these countries.

Dedicated adolescent wards provide a focal point from which a hospital can promote best practice in adolescent health. Australia is widely acknowledged as a model of leadership in adolescent medicine. It has focused on achieving adolescent centres of excellence in Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. These units provide developmentally appropriate health care with routine psychosocial screening and support for young people admitted with a diverse range of conditions.

The Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Centre, based in New York City’s East Harlem community is recognised as a leading academic adolescent centre for healthcare provision, research and training in the United States. It supports a diverse population of adolescents and young adults aged between 10 through 22 years. Healthcare for more than 11,000 patients per year is provided. There are approximately 50,000 appointments for adolescents each year in this unit. [xi] Specialist services including sexual and reproductive health, substance abuse prevention and treatment, health promotion, mental health and family counselling services are available.

The models for adolescent healthcare in Australia, the United States and Canada favour a number of key facilities for adolescent units. Wards typically consist of a mixture of open bays and single or shared rooms. Bays are arranged on a single-sex basis where possible. Young people requiring isolation have single rooms. Separate examination rooms, treatment rooms, and private interview rooms are considered essential to maintaining confidentiality and dignity throughout their inpatient stay. Within the context of a holistic model of care, dedicated youth-friendly spaces provide a therapeutic milieu, enabling peer support, education and creative expression. A supportive ward environment for adolescents develops young people's self-management skills and supports their emerging independence with healthcare. This in turn facilitates a smoother transition to adult services.

In marked contrast to our international counterparts, expenditure on adolescent healthcare training in Ireland has been limited to date, and this population as a consequence has been largely neglected. An expanded workforce capable of providing comprehensive adolescent-responsive healthcare in Ireland must be obtained to ensure an age appropriate environment for patients at this sensitive developmental age and a more standardised and structured approach to patient care.

The stereotypical Irish media portrayal of young people is primarily negative and simplistic, often with an emphasis on anti-social behaviour and criminality. Yet the majority of Irish adolescents undisputedly make a valuable and positive contribution to our society. Growing recognition of the crucial roles adolescents play in today’s society has spurred an expanding global movement to address the healthcare requirements of this unique cohort. Investments in Irish adolescent health will bring a triple dividend of health benefits to our society –improved adolescent health, adult health and also the health of future generations. The ‘Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women's, Children's, and Adolescents' Health’ [xii] explicitly illustrates the pivotal role of adolescents in achieving radical change for a prosperous, healthy, and sustainable society.

To conclude, although a convenient way to define adolescence, age is only one characteristic that delineates this complex period of development. The Irish healthcare agenda needs to be advanced to ensure the highest attainable standards for health and wellbeing for this valuable, yet vulnerable generation. Further investment will help shape the fledgling discipline of ‘adolescent health’ in Ireland.

‘There is in every child at every stage a new miracle of vigorous unfolding.’

Erik Erikson (1902-1994)

Correspondence

Dr. Bronwyn Power, Department of Paediatrics, University Hospital Limerick, St. Nessan’s Road, Dooradoyle, Co. Limerick

Tel: 0035361301111

Email: [email protected]

References

i. Central Statistics Office of Ireland. Population and Migration Estimates for April 2016. Available from: http://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2016/. (Accessed 12/12/2016).

ii. National office for suicide prevention. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/Mental_Health_Services/NOSP/SuicidePreventionie/suicideselfharm/ (Accessed 02/10/2017).

iii. O’Neill B, Dinh T. Cyberbullying among 9-16 year olds in Ireland.Ireland: Irish Research Council; 2013. Available from http://rathfeighns.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Cyber-Bullying.pdf

iv. Platt H. The Welfare of Children in Hospital.Report of the committee on child health services, London, HMSO. 1959.

v. Dodds H. Meeting the needs of young people in hospital. Paediatric Nursing; 2010. 22( 9), 14-18.

vi. Viner RM. Do Adolescent Inpatient Wards make a Difference? Findings From a National Young Patient Survey. Pediatrics Oct 2007, 120 (4) 749-755.

vii. Menzies-Lyth I. The Psychological Welfare of Children Making Long Stays in Hospital: an Experience in the art of the Possible. Occasional Paper No 3. The Tavistock Insitute of Human Relations, London; 1982.

viii. Busen N. Perioperative preparation of the adult surgical patient. AORN Journal,2001; 73, 2, 337-363.

ix. Patton G.C., Ross D.A., Santelli J.S., Sawyer S.M., Viner R.M., Kleinert S.(2014). Next steps for adolescent health: A Lancet commission. The Lancet, 383 (9915) , pp. 385-386.

x. Lee L, Upadhya KK, Matson P, Adger H, Trent ME. The status of adolescent medicine: Building a global adolescent workforce. International journal of adolescent medicine and health. 2016;28(3):233-243.

xi. Available from http:www.mountsinai.org/locations/services (Accessed 02/08/2018)

xii. Every woman every child; ‘The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and adolescents’ health (2016-2030)’. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/events/2015/gs_2016_30.pdf . (Accessed 19/10/2017).

P819