Disseminated Mycobacterium africanum in an Immunocompetent Child

Tuberculosis is among the top 10 causes of paediatric mortality worldwide. Ireland has a low incidence however (6.9/100,000 population/year), TB meningitis 0.07/100,000 population/year. We report the first paediatric case of disseminated TB including meningitis in Ireland caused by Mycobacterium africanum. All 3 previous paediatric cases of M. africanum TB, presented with extrapulmonary symptoms1.

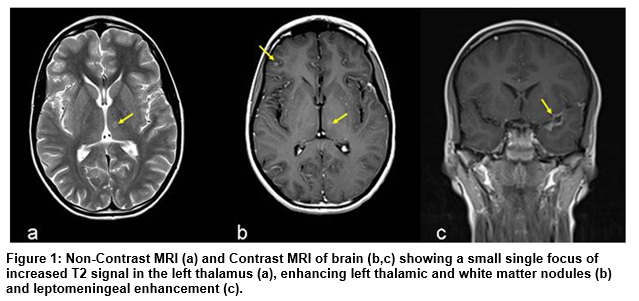

A 10-year-old boy, born in Ireland to Nigerian parents, presented with pyrexia of unknown origin. He had received BCG vaccination. A small cervical lymph node was noted on examination, which was otherwise normal. He complained of headache without meningism. Chest X-ray was normal, and inflammatory markers mildly raised. Mantoux test was positive after 48 hours. A non-contrast MRI of brain demonstrated a focus of increased T2 signal in the left thalamus (Figure 1a).

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) analysis was highly suspicious for TB meningitis. Isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide were commenced. Acid fast bacilli (AFB) were not seen on microscopy. CSF culture, including TB culture, and virology studies were negative.

An abdominal ultrasound showed large volume lymphadenopathy. A contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated ‘tree-in-bud’ pulmonary nodularity, lymph nodes in the mediastinum and upper abdomen, low attenuation lesions in the liver and heterogeneous renal enhancement.

Contrast-enhanced MRI brain demonstrated enhancing left thalamic and white matter nodules and abnormal leptomeningeal enhancement (Figure 1b, c), consistent with disseminated, parenchymal and leptomeningeal TB. A total of 8 weeks of high dose steroids were used.

Fine needle aspiration of the cervical lymph node showed AFB on Auramine and Ziehl Neelsen staining. Histology showed caseous necrosis and a single multinucleate giant cell with scattered histiocytes. All findings supported the diagnosis of disseminated tuberculosis with central nervous system involvement. Immune work-up was normal.

Culture of the cervical node aspirate yielded a mycobacterial species after 28 days incubation, identified as Mycobacterium africanum by molecular analysis (Genotype® MTBC, Hain lifescience). Drug testing showed full susceptibility (BD Bactec™ MGIT™ 960).

The patient has fully recovered after one year of treatment. The asymptomatic father was found to be affected.

Human tuberculosis is caused by bacteria from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MBTC), which includes M tuberculosis, africanum, microti, canetti, caprae, pinnipedii, and bovis. M. africanum is found almost exclusively in West Africa but is rare in Europe2. It is clinically indistinguishable from other MBTC sub-species, with a similar degree of infectivity as M. tuberculosis, but is less likely to progress to clinical disease in immunocompetent individuals3. Disseminated TB and meningitis (TBM) are usually found in very young and/or HIV-infected children. In TBM treatment delay has high mortality therefore adjunctive corticosteroids are recommended.

Due to current shortage of BCG, a selective vaccination program which considers parents’ country of origin has been instituted4. As the protective efficacy of BCG varies a history of vaccination should never preclude diagnosis of TB infection. This case highlights the importance of family country of origin in cases of pyrexia and meningitis. The absence of pulmonary symptoms and the disseminated nature of the infection were striking. Clinical and radiological clues were critical for diagnosis and management.

Authors:

1S Giva, 1S Geoghegan, 2C Hickey, 3C Bogue, 4K Butler, 1D Mullane, 1S M. O’Connell,

1Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

2Department of Microbiology, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

3Department of Radiology, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

4Department of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Our Lady’s Children´s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin, Ireland

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not declare any conflict of interest

Corresponding author

Susan M O’Connell

Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork, Ireland

E-mail: [email protected]

Phone number: +353 21 49 20139

References

1.Annual Reports – Health Protection Surveillance Centre [Internet]. Hpsc.ie. 2016 [cited 8 March 2016]. Available from: http://www.hpsc.ie/A/VaccinePreventable/TuberculosisTB/Epidemiology/AnnualReports/

2. de Jong B, Antonio M, Gagneux S. Mycobacterium africanum – Review of an Important Cause of Human Tuberculosis in West Africa. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4 (9):e744

3. de Jong, B. C., Hill, P. C., Aiken, A., Jeffries, D., J., Onipede, A., Small, P. M., Adegbola, R. A., Corrah, T. P. Clinical presentation and outcome of tuberculosis patients infected by africanum versus M. tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007, 11(4): 450-6

4. Health technology assessment of a selective BCG vaccination programme | hiqa.ie [Internet]. Hiqa.ie. 2016 [cited 8 March 2016]. Available from: https://www.hiqa.ie/publications/health-technology-assessment-selective-bcg-vaccination-programme

p443