Diversion of Mentally Ill Offenders from the Criminal Justice System in Ireland: Comparison with England and Wales.

1G Gulati, 2BD. Kelly

1Consultant General & Forensic Psychiatrist, Limerick Prison, Limerick.

2Professor of Psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Abstract

Aim

It is generally accepted that certain people who are mentally ill and have contact with the criminal justice system should be diverted to psychiatric care rather than imprisoned. We sought to comment on priorities relating to the development of diversion services in Ireland through comparison with developments in a neighbouring jurisdiction.

Methods

A comparative review was undertaken in relation to the provision for psychiatric diversion across the offender pathway in Ireland and England and Wales. This included legal and service related considerations.

Results

In both jurisdictions, services show significant geographical variability. While developments in England and Wales have focussed on the broader offender pathway, diversion services in Ireland are chiefly linked to imprisonment. There is little or no specialist psychiatric expertise available to Gardaí in Ireland. Prison In-reach and Court Liaison Services (PICLS) are developing in Ireland but expertise and resourcing are variable geographically. There is a lack of Intensive Care Regional Units (ICRU) in Ireland, in sharp contrast with the availability of Intensive Care and Low Secure Units in England and Wales. There is limited scope to divert to hospital at sentencing stage in the absence of a ‘hospital order’ provision in Irish legislation.

Conclusions

Three areas in the development of Irish diversion services should be prioritised. Firstly, the provision of advice and assistance to Gardaí at arrest, custody and initial court hearing stages. Secondly, legislative reform to remove barriers to diverting remand prisoners and facilitating hospital disposal on sentencing. Thirdly, an urgent need to develop of ICRU’s (Intensive Care Regional Units) to facilitate provision of appropriate care by local mental health services.

Introduction

Irish prisoners have high rates of mental illness1 in keeping with the picture worldwide2. Since the 1970’s, prisoner numbers in Ireland have quadrupled while the number of psychiatric hospital beds has decreased. There is international consensus about the need to provide treatment to those who suffer with a serious mental illness and find themselves in contact with the law3. Both England and Wales and Ireland have introduced new mental health and criminal justice legislation in the twenty-first century and these were potential opportunities to promote psychiatric diversion as a key principle in the criminal justice system. These may have been potential missed opportunities. Diversion services had been developing in the England and Wales since the late 1980’s4 and have thus had more time to evolve than in Ireland, where development of diversion services has occurred largely over the past 15 years.

Method

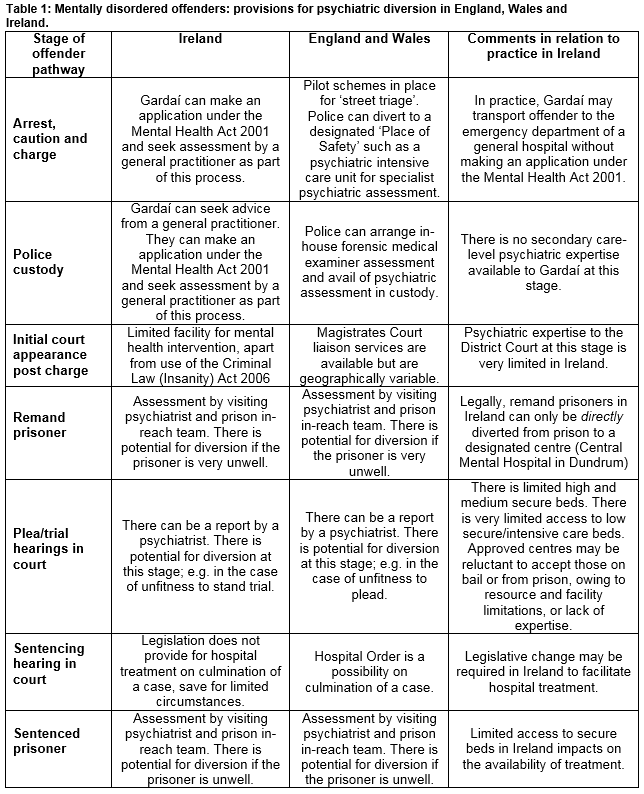

In this paper, we compare provision for psychiatric diversion across the offender pathway in Ireland and England and Wales, and comment on priorities for further development in Ireland. Table 1 provides an overview of the main provisions for diversion across the offender pathway in England, Wales and Ireland.

Results

In both jurisdictions, services are still developing and both show significant geographical variability. While developments in England and Wales have focussed on the broader offender pathway, diversion services in Ireland are chiefly linked to imprisonment. In contrast with England and Wales, there is little or no specialist psychiatric expertise available to Gardaí in Ireland who have a prisoner in custody or to Court services at the initial hearing. This potentially increases imprisonment rates of the mentally ill, to the clear detriment of those whose alleged offending is extremely minor and likely attributable to their illness.

Prison In-reach and Court Liaison Services (PICLS) are developing in Ireland but expertise and resourcing are highly variable geographically. Outcomes from the flagship PICLS project in Dublin are extremely positive5. There is, however, a lack of Intensive Care Regional Units (ICRU) in Ireland, in sharp contrast with the availability of Intensive Care and Low Secure Units in England and Wales, and this impacts negatively on psychiatric diversion from court and custody in Ireland.

Approved Centres (‘open wards’ or local inpatient psychiatric units) in Ireland are often reluctant to accept patients with offender status owing to inadequate resources, inappropriate facilities or lack of expertise. Irish remand prisoners can be directly diverted only to a ‘designated centre’ and the Central Mental Hospital in Dundrum, the only ‘designated centre’ in the country, has insufficient capacity, with the lowest per capita bed number in comparison to European counterparts6. The alternative course is to propose bail at a future court hearing and use civil detention under the Mental Health Act 2001, but this can prove a complex, delayed process, and depends critically on the ability of local approved centres to accept the patient. Finally, there is limited scope to divert to hospital at sentencing stage in the absence of a ‘hospital order’ provision in Irish legislation (as in England and Wales). For sentenced prisoners, legal frameworks for diversion exist in both jurisdictions.

Discussion

Against this background, there are clearly multiple areas in need of development in relation to psychiatric diversion in Ireland7. Three areas should be prioritised. First, the provision of advice and assistance to Gardaí at arrest, custody and initial court hearing stages should be improved. Evidence from the England and Wales indicates that such schemes produce positive outcomes for those with mental illness8. Second, legislative reform is necessary to remove barriers to diverting remand prisoners and facilitating hospital disposal on sentencing. Experience from other jurisdictions suggests that legislative reform can be a key driver and not just a facilitator of change9. The issue of resourcing is also critical, in terms of local facilities and expertise.

Third, there is an urgent need to develop of ICRU’s to facilitate provision of appropriate care by local mental health services. Intensive care facilities are only present in one setting each in Dublin and Cork at present and have limited catchment areas. While those who have committed serious offences and suffer major mental illness are diverted to the Central Mental Hospital, in the absence of ICRU’s there will continue to be limited diversion to local services of those charged with minor offences but suffering major mental illness.

Finally, future research could usefully focus further on tracking outcomes for people with mental illness who come into contact with the criminal justice system in Ireland: do they get the help they need when they need it? International evidence would suggest that investing in the provision of such care would not just benefit the individuals themselves,4 but would also benefit society at large through reduction in recidivism,4 and have significant economic benefits for the state10.

Conflict of Interest

I can confirm that there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Correspondence:

Gautam Gulati FRCPsych, Consultant General & Forensic Psychiatrist, Limerick Prison, Limerick.

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Kennedy HG, Monks S, Curtin K, Wright B, Linehan S, Duffy D, Teljeur C & Kelly A. Mental Illness in Irish Prisoners. Dublin: National Forensic Mental Health Service, 2004. Available at: http://www.tara.tcd.ie/handle/2262/63924

2. Fazel S & Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide:

systematic review and meta-regression analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012; 200: 364–373.

3. World Health Organisation (2005). Mental health: facing the challenges, building solutions : report from the WHO European Ministerial Conference. Denmark: World Health Organisation, 2005. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/96452/E87301.pdf.

4. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. Diversion: A better way for criminal justice and mental health. London: Nuffield Press, 2009.

5. McInerney C, Davoren M, Flynn G, Mullins D, Fitzpatrick M, Caddow M, Quigley S,

Black F, Kennedy HG & O’Neill C. Implementing a court diversion and liaison

scheme in a remand prison by systematic screening of new receptions: a 6 year participatory action research study of 20,084 consecutive male remands. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2013; 7: 18.

6. Kennedy H. Opinion: Prisons now a dumping ground for mentally ill

young men. 18 May 2016. The Irish Times. Available from: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/opinion-prisons-now-a-dumping-ground-for-mentally-ill-young-men-1.2651034

7. Department of Justice. First Interim Report of the Interdepartmental Group to examine issues relating to people with mental illness who come in contact with the criminal justice system. Dublin: Department of Justice, 2016. Available at: http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/interdepartmental-group-to-examine-issues-relating-to-people-with-mental-illness-who-come-in-contact-with-the-criminal-justice-system_first-interim-report.pdf/Files/interdepartmental-group-to-examine-issues-relating-to-people-with-mental-illness-who-come-in-contact-with-the-criminal-justice-system_first-interim-report.pdf

8. Reverruzzi B & Pilling S. Report on the evaluation of nine pilot schemes in England. London: University College London, 2016. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/pals/research/cehp/research-groups/core/pdfs/street-triage

9. Hartford K, Davies S, Dobson C, Dukeman C, Furhman B, Hanbidge J, Irving D, McIntosh E, Mendonca, J, Peer I, Petrenko M, Voigt V, State S, Vandevooren J. Evidence-based practices in diversion programs for persons with serious mental illness who are in con ict with the law: literature review and synthesis. Ontario: Ontario Mental Health Foundation and Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2004. Available at: http://bcm.connexontario.ca/Resource%20Library/Court%20Diversion-Support%20Programs/Evidence-Based%20Practices%20in%20Diversion%20Programs%20for%20Persons%20with%20Serious%20Mental%20Illness%20Who%20are%20in%20Conflict%20w%20the%20Law%202004.pdf

10. Centre for Mental Health. Diversion: the business case for action. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2010. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Diversion_business_case.pdf

(P719)