Fracture Patients’ Attitudes towards Online Health Information & a ‘Prescribed’ Fracture Website

Clesham, JG. Galbraith, SR. Kearns, ME. O’ Sullivan

Department of Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgery, Galway University Hospitals, Galway

Abstract

Introduction

Following musculoskeletal injury patient education is essential to help patients understand their treatment. Many attend the orthopaedic fracture clinic with multiple questions related to their diagnosis and treatment.

Aim

To assess trauma patients’ attitudes towards online health information and a specific orthopaedic patient information website.

Methods

A validated questionnaire was distributed over 5 consecutive clinics, with questions based on previous online experiences & www.myorthoclinic.com.

Results

One hundred six patients completed the survey. Seventy-one percent trusted the internet whereas 83% trusted the information provided by the website. Eighty-three percent felt encouraged to take action to benefit their health. Eighty-seven percent felt that there was a wide range of information provided. Seventy-two percent agreed that they learnt something new.

Discussion

Patients attending the trauma clinic have benefited from the ‘prescribing’ of a dedicated orthopaedic trauma website. This low-cost concept utilises minimal resources, requires little effort to implement and is applicable to all specialties.

Introduction

The availability of the internet has grown rapidly over the past 20 years. In the Republic of Ireland in 2016 87% of households were connected to the internet, an increase of 28% from 2009 demonstrating the rise in this area1. It is now accessible through a variety of platforms including smartphones, tablets and laptops with 83% of the population regularly using smartphones to browse the internet1. Numerous studies have shown the growing use of the internet by patients to learn more about their condition2-5. A search for the terms ‘bone fracture’ on Google’s search engine returns 76,500,000 results, many of these resources however are not validated by expert authorities and may contain misinformation which can adversely affect patients’ understanding and expectations. It has been suggested previously that doctors should actively recommend websites to help patients make decisions and learn more about their conditions7.

Conventional medicine relies more on shared decision making between the doctor and the patient, as opposed to the paternalistic role that the doctor played in the past. Patient education is becoming more and more important as patients become more active in their treatment. Given how the internet permeates almost all other aspects of our lives, it is only logical that a validated medical information website would form an integral part of a patient’s treatment. With this in mind, we aimed to investigate fracture patients’ attitudes towards searching for health information online, and on a recommended orthopaedic website to assess opinions on their experience of a ‘prescribed’ website. www.myorthoclinic.com is a website that provides a range of information to musculoskeletal trauma patients8. The website was created by a senior orthopaedic trainee with input from experienced orthopaedic trauma consultants and provides information on various aspects of diagnosis, management, prognosis and prevention measures. It includes a user-friendly platform with suitable language to help fracture patients understand what to expect in clinic as well as answer many of the frequently-asked questions they may have in the clinic. It also covers important topics around wound and cast management such as guidelines around flying, driving and washing.

Methods

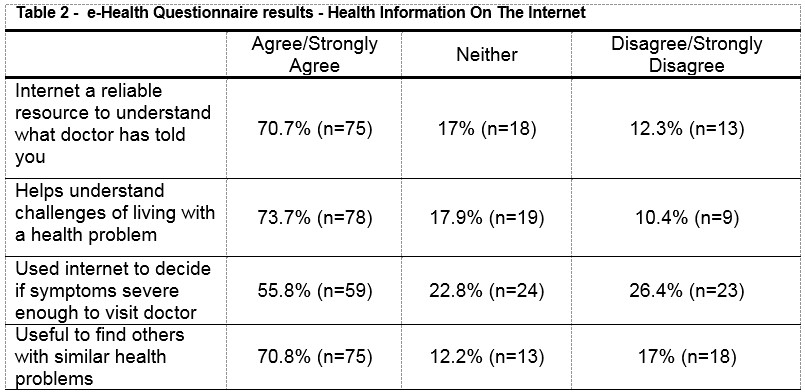

A two-part questionnaire was developed and used for the purpose of this study. These were distributed to patients attending a fracture clinic who had sustained a musculoskeletal trauma in the previous four weeks. A modified version of the ‘e-Health Questionnaire’ formed the first part of the survey, which asks questions about previous experiences in searching for

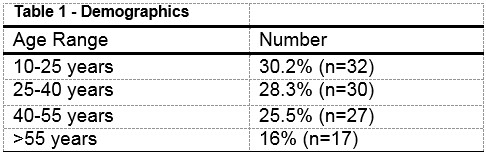

health information on the internet9. The participants were then asked to search for the website ‘www.myorthoclinic.com’ on their smartphones and spend 5 minutes browsing in their area of interest8. Patient consent was obtained at the time of survey distribution. Demographics recorded included age and sex, and agreement with statements in the survey were recorded as ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘neither’, ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’. Age distribution was categorised into 10-25 years of age, 25-40 years, 40-55 years and above 55 years.

Attitudes towards using health information for diagnosis, seeking other patient experiences and validating doctors’ advice was surveyed in part one of the questionnaire. In part two, the participant’s impression of the level of information, perceived validity and information learned from the prescribed website was surveyed. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 14.2 for Mac. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis was used to correlate age groups with specific questions.

Results

One hundred and six participants completed the survey (65 females, 41 males) with age demographics displayed in table one. Ten participants did not complete the survey due to lack of access to the internet at that time. The e-health questionnaire results are shown in table two. Thirty-four percent (n=36) agreed or strongly agreed that they used the internet to check if the advice they were given by a doctor was appropriate. Seventy-three percent (n=76) thought that it was helpful to go online to learn of other patient’s health-related experiences. Seventy-six percent (n=80) felt reassured that they are not alone with their health problem.

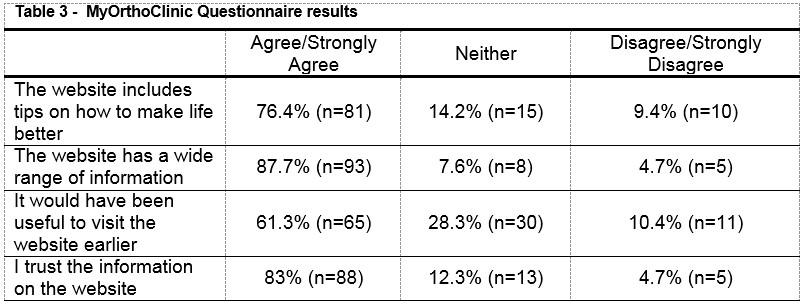

After browsing the website the second part of the questionnaire was carried out displayed in table 3. 75% (n=81) agreed it included useful tips on improving their health awareness. In total, 83% (n=88) found the language easy to understand and 72% (n=76) learned something new from their visit.

When asked if the site provided more useful information than the doctor is likely to give, 22% (n=23) agreed, 47% (n=49) disagreed with the remainder (31%) answering ‘neither’. Ninety percent (n=95) found the site easy to use. The >55 year age category were less likely to trust the information on the site when compared with all other groups (p=0.007). They also disagreed that the site offers more information than the doctor (p=0.034) and found it more difficult to understand (p= <0.001).

Discussion

The modified e-Health Questionnaire provided interesting insight into patients’ perspectives on both health information from the internet and from the validated orthopaedic website www.myorthoclinic.com. Irish patients with a musculoskeletal injury regard the internet as good for reliability, accessibility and as a source of information and moderate at helping determine indications for visiting a doctor. With regard to the website, most importantly, trust in www.myorthoclinic.com was higher at 83%, than that of the internet at large (70%) and distrust was lower (4.7% v 17%). Secondly, the wide range of information from the website, (87%) indicates its comprehensive approach to answering patients’ questions and concerns. Patients still value the face-to-face consultation with the doctor for gaining information about their injury - only 22% felt that it was more useful than what the doctor is likely to give.

The waiting room at the fracture clinic was an ideal setting to access patients for this study as the majority had access to the internet via their smartphones while waiting to be seen. One has to assume that individuals vary from internet-savvy to internet-naïve. Most of these patients were attending for the first time in the trauma clinic after being referred from the emergency department or being followed up for recent injuries. Unsurprisingly, only 61% would have found the website more helpful if they visited it earlier. Patients who are well-educated on the nature of their condition and rehabilitation required will have a greater level of insight and can set realistic targets for themselves during their recovery. One can observe the potential for patient empowerment in this study as 71% found it useful to find out about other patient experiences. Unfortunately some resources are not validated and may provide the patient with incorrect information. The possibility of misinformation gleamed from such sites can lead to elevated expectations for treatment and management which can be problematic when making plans with the patient10. These figures echo the findings of Fraval et al, who showed that 65.2% of patients used the internet to investigate their orthopaedic condition5. The current ‘information era’ has led to patients becoming more educated about their condition and the type of treatments available. It can also lead to strains in the patient-doctor relationship which may promote further difficulties in the clinical setting11.

The Orthopaedic fracture clinic tends to be a busy unit that accommodates large patient numbers on a daily basis. This can occasionally lead to reduced amounts of time spent in consultation with each patient, posing difficulties in imparting all of the necessary information in a short period of time. On first presentation to the clinic, patients generally have many questions related to their diagnosis and prognosis. For those who have undergone a surgical procedure or who may require one, additional time is required to explain the procedure along with the relevant risks and benefits. It can be difficult to ensure all aspects of the patients care are discussed in a short clinic consultation. Patients may forget to ask important questions related to their care, and may use the internet to help answer their queries. The idea of ‘prescribing’ a website has been discussed previously by Jariwala et al7. At the end of the consultation a specific verified website is recommended to the patient to aid their understanding. This concept ensures the patient has a resource that can provide information based on the latest clinical evidence. It has also been shown that providing online information leads to better retention of information when consenting patients for orthopaedic procedures12. Websites that are approved by national authorities or recognised organisations should be recommended to ensure quality information is being provided.

On further analysis, the oldest age group (>55 years) were shown to have less trust in the information given by the website (p=0.007), found it harder to understand (p=<0.001) and believed the doctor had more information (p=0.034) to offer. From this we can predict that the younger generation will benefit most from the use of online information, whereas older patients may require some extra time spent in consultation with their doctor or alternative resources. One of the reasons for this may be the complexity of the information on the internet. This has been described as a problem in healthcare, and numerous papers have confirmed that the reading levels of some websites is above national averages13. O’Neill et al showed that just 13.7% of websites related to elective orthopaedic information were set at or below the recommended 6th-grade reading level14. This portrays the importance of selecting suitable websites that patients will understand and benefit from.

This study was carried out in the trauma clinic, and although most patients had smartphones with internet capability there were a small number who could not participate due to lack of phone or internet. One hundred and fourteen patients were recruited with 106 fully completing the surveys. As technology continues to advance we can expect a more streamlined online experience with increased use among all age groups.

Patients attending the orthopaedic trauma clinic have experienced a benefit from a dedicated orthopaedic trauma website, with the aim informing patients about their condition. This concept utilises minimal resources, requires little effort and can be applied across all surgical and medical specialties.

Conflicts Of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest in relation to this paper

Correspondence

Dr Kevin Clesham, Department of Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgery, Galway University Hospitals, Galway

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Central Statistics Office (2016) Information Society Statistics - Households Available from: http://pdf.cso.ie/www/pdf/20161220090317_Information_Society_Statistics__Households_2016_full.pdf.

2. Wright JE, Brown RR, Chadwick C, Karadaglis D. The use of the Internet by orthopaedic outpatients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1096-7.

3. Gupte CM, Hassan AN, McDermott ID, Thomas RD. The internet--friend or foe? A questionnaire study of orthopaedic out-patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84(3):187-92.

4. Jariwala AC, Kandasamy, Abboud RJ, Wigderowitz CA. Patients and the Internet: a demographic study of a cohort of orthopaedic out-patients. Surgeon. 2004;2(2):103-6.

5. Fraval A, Ming Chong Y, Holcdorf D, Plunkett V, Tran P. Internet use by orthopaedic outpatients - current trends and practices. Australas Med J. 2012;5(12):633-8.

6. www.google.com [Available from: www.google.com.

7. Jariwala AC, Paterson CR, Cochrane L, Abboud RJ, Wigderowitz CA. Prescribing a website. Scott Med J. 2005;50(4):169-71.

8. Myorthoclinic.com [Available from: http://myorthoclinic.com/.

9. Kelly L, Ziebland S, Jenkinson C. Measuring the effects of online health information: Scale validation for the e-Health Impact Questionnaire. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(11):1418-24.

10. Hungerford DS. Internet access produces misinformed patients: managing the confusion. Orthopedics. 2009;32(9).

11. McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1-2):24-8.

12. Fraval A, Chandrananth J, Chong YM, Coventry LS, Tran P. Internet based patient education improves informed consent for elective orthopaedic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:14.

13. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):199-204.

14. O'Neill SC, Nagle M, Baker JF, Rowan FE, Tierney S, Quinlan JF. An assessment of the readability and quality of elective orthopaedic information on the Internet. Acta Orthop Belg. 2014;80(2):153-60.

(P732)