Ghana Health Services and the Irish health system – bridging the gap.

Akaateba D1,5, Andan M1, Hadfield K1,2, Elmusharaf K2, Leddin D2,3, Murphy F2,4, Ofosu W5, Sheehan C4, Finucane P2,4.

1Ghana Medical Help.

2University of Limerick.

3Dalhousie University, Canada

4University of Limerick Hospitals Group

5Upper West Region Health Service,Ghana.

Introduction

The University of Limerick Hospitals Group (ULHG), and the University of Limerick (UL), are committed to fostering links with the developing world and contributing to solutions of the challenges these countries face. In 2016 a group from UL and ULHG visited the Upper West Region of Ghana1 to explore the possibility of establishing a partnership with Ghana Health Services (GHS). In this article, we describe aspects of GHS and outline some of the challenges for Irish institutions trying to engage with the realties of the developing world.

Background

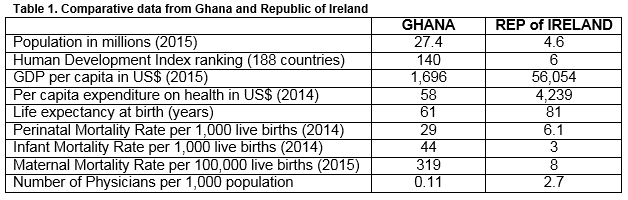

Ghana ranks at 140 of the 188 countries listed in the World Bank’s Human Development Index2. A quarter of the population is described as poor and some 10% live in extreme poverty3. In 2014, its per capita expenditure on health was US$58, compared to an average of US$95 for Sub-Saharan African countries, US$4,239 for Ireland and US$9,403 for the US.4

The Ghanaian model of Health Care

GHS is a national, public service that provides free but extremely limited health care to all children up to the age of five years and to all adults aged over sixty. All citizens are encouraged to enroll in the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) - a voluntary government-sponsored scheme which provides free access to most, but not all, diagnostic and therapeutic services in public health facilities for an annual subscription of €5 per person5. Overall, some 80% of the population have either free access to health care because of age or are covered by NHIS. Most of the services at Tertiary Hospitals are also provided free of charge to NHIS members, but expensive investigations (e.g. CT, MRI) and some treatments are neither readily available nor covered. While just a small percentage of the population has private health insurance, private spending on health is one of the highest in Africa.

The salaries of government-funded health care worker range from €125-€200 per month for a Community Nurse; €500 per month for a Physician Assistant to €1,000 per month for a doctor. There are major funding and cash flow problems. For example, many basic services are simply unfunded and government payments to support regional health services are often delayed. The public system is supported in part by international aid. Self-funding Mission Hospitals from Ghana’s pre-independence years have now largely been replaced by a plethora of overseas aid programs. Heath care provision throughout Ghana is provided at five levels. All facilities operate on a 24/7 basis and all employees are government funded.

Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) facilities provide the cornerstone for health care delivery nationally.6 These are widely distributed throughout Ghana, with 222 facilities in the Upper West Region alone (i.e. one CHPS facility per 2,600 people). CHPS facilities are generally one or two-roomed buildings which are normally staffed by two Community Health Workers (CHWs), one of whom is likely to have midwifery skills. CHWs undergo a two-year formal training programme; their work focuses on disease prevention, on ante-natal care and on the treatment of minor illness. They also operate a national immunization programme, undertake school visits and visit sick people in their own homes. Increasingly, they undertake low-risk deliveries and many communities have built birthing units on CHPS compounds. Attendees with significant illness or with perinatal problems are referred to higher order facilities. CHWs reside in CHPS facilities so as to increase their availability to the community.

Health Centres are staffed by Physician Assistants who have a nursing background and who then receive advanced training7. They treat common medical conditions and especially communicable diseases such as malaria, gastroenteritis, etc. Health Centre midwives supervise low-risk deliveries, though increasingly such deliveries are undertaken at CHPS facilities. There are 64 Health Centres in the Upper West region, serving an average of 9,000 people each. District Hospitals are normally staffed by between one and three doctors and a higher complement of Physician Assistants and nurses. They provide a wide range of clinical care for patients with surgical, medical, paediatric and obstetric/gynaecological problems. They offer a modest range of basic diagnostic services – e.g. plain X-ray, ultrasonograpy, laboratory investigations. There are seven district hospitals in the Upper West Region – i.e. each District Hospital here serves an average of 83,000 people.

Regional Hospitals, with one such hospital for each of the country’s ten administrative regions. That for the Upper West Region is at Wa, the regional capital, and is a 200-bed facility that usually accommodates 400 patients at a given time and serves the regional population of 580,000. It provides a more comprehensive range of medical, surgical, pediatric and obstetric/gynecological services than the region’s District Hospitals. It also offers basic diagnostic services including plain X-ray, ultrasonography and laboratory investigations. Tertiary Hospitals are larger and better staffed than Regional Hospitals and have greater access to diagnostic and therapeutic services, including CT and MRI scanning. That closest to Wa is at Tamale, a five-hour drive away and this serves the entire northern region and its population of five million people.

Challenges

At every level of care human and technical resources are scarce. There are essentially no primary care physicians, and almost no specialist medical services. Ghana is also challenged by demands for health care resulting from the cross-border migration of refugees from even more impoverished bordering countries; Togo, Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. Despite the challenges the health status of Ghanaians has steadily improved with life expectancy at birth now standing at 61 years, up from 46 years in 1960. Ghana has also greatly improved objective measures of population health status such as its Perinatal, Infant and Maternal Mortality Rates.

Maternal mortality is a particular concern to the GHS. In 2015 only 45% of women in the Upper West region had some antenatal care, 33% had the benefit of a skilled delivery. Sixty percent of the deaths occurred outside medical facilities, which is consistent with the lack of antenatal care. Seventeen percent of the deaths were from hemorrhage, 7% were from sepsis and septic abortion. In 76% the cause was not known, or not listed. The majority of these deaths occurred in rural areas outside the medical care network.8 Improvement in maternal mortality in the Upper West region has been ascribed in part to the work of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) which has built 64 CHPs compounds and trained over 900 workers. 9 With increasing affluence comes an increasing burden of non-communicable diseases in addition to that characteristic of low-income countries. Problems such as diabetes and hypertension are emerging as the economy grows. Irish health care providers can help the GHS to address these new demands.

Where can we help?

The Ghanaian model of care is structurally very different from that in Ireland10. There is no physician-led primary care network and a reliance on community health workers with little training and few resources to deliver front line care. Specialist resources are minimal; for example, there is one pediatrician for a population of five million in the north. Diagnostic facilities and pharmaceuticals are in short supply. Although the health delivery system is based on triage and movement from lower acuity to higher acuity facilities the limited transportation infrastructure is a huge obstacle. For example, the one ambulance in the Upper West region is non-functional. Thus, there is no means to transport obstetric emergencies from rural areas and grossly inadequate access to blood transfusion at hospital level. The paucity of human, financial and technical resources make it very difficult for any outside organization to determine where best to engage since much of the skills, and knowledge applicable to Irish health care is irrelevant.

In 2016, the ULHG/UL delegation met with senior GHS administrators, physicians and nurses and community health workers in the Upper West region and elsewhere. The priorities identified were maternal mortality, neonatal mortality and trauma. Enhanced community health care as delivered through the CHPS clinics is considered crucial and ULHG/UL were asked to focus on supporting this. To this end, we are now developing education and training programmes which will be delivered both locally and remotely and which will involve primary care, paramedics, nursing and health system administration aimed at front line health care workers.

The work of JICA and others demonstrates that outside agencies can engage meaningfully with GHS to improve outcomes. A long-term commitment from Irish institutions will be critical to success. Without institutional support, projects such as those we are developing are not sustainable. Other Irish health care groups are engaging with the developing world11. We look forward to collaborating with colleagues, both in Ireland and internationally, who are pursuing similar goals to positively affect health outcomes in Africa.

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm no conflict of interest.

Correspondence:

Desmond Leddin, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, B3H 4R2

Email: [email protected]

References

1. The Upper West, Government of Ghana, cited 29 August 2016, http://www.ghana.gov.gh/index.php/about-ghana/regions/upper-west

2. United Nations. Human development report 2015, United Nations Development Program. 2015. Cited 28 August 2016.http://hdr.undp.org/en/2014-Report

3. Philomena Nyarko, Ghana Statistical Service. 2014. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6: Poverty Profile in Ghana, 2005-2013. Government of Ghana 2014, 28 August 2016. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/glss6/GLSS6_Poverty%20Profile%20in%20Ghana.pdf

4. Health expenditure per capita. World bank 2014. 28 August 2016. . http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP

5. National Health Insurance Scheme. Government of Ghana. http://nhis.gov.gh Accessed: 28 August, 2016.

6. Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA. 2005. The Ghana Community-based Health Planning and Services Initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy and Planning; 20: 25-34.

7. Adjase ET. 2015. Physician Assistants in Ghana. J Am Acad Phys Assistants; 28(4): 15.

8. Ghana Health Services. Annual report 2015. Personal communication

9. Dominic Moses Awiah. Upper west records decline in maternal, neonatal deaths. Graphic online. 2016. August 2016. http://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/upper-west-records-decline-in-maternal-neonatal-deaths.html

10. Drislane FW, Akpalu A, Wegdam HHJ. 2014. The Medical System in Ghana. Yale J Biol Med; 87: 321-326.

11. ESTHER Ireland. Partnerships. 2016. September 2016. http://www.esther.ie