Hidden Costs in Paediatric Psychiatry Consultation Liaison Services.

C Kehoe 1,2, F. McNicholas 1,2,3

1 Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin;

2 School of Medicine and Medical Science, Geary Institute, UCD;

3 Lucena Clinic Services, Rathgar, Dublin, Ireland.

Abstract

Aim

Children with acute mental health (MH) concerns increasingly present to Emergency Departments, and in the absence of an accessible MH bed, are admitted. This study estimated the hidden associated costs.

Methods

All Emergency MH admissions over a 12-month period (2016) were identified (N=105). Costs associated with length of stay (LOS) and one-to-one nursing were calculated.

Results

The average Length of Stay for acute MH presentations was 6 days, there were 615 bed day associated with this cohort, totalling costs of €1,216,470, with an average cost/patient of €12,684. Sixty-eight patients (65%) required an average of 5 days of one-to-one nursing, totalling 335 days. Estimating that 40% of this was provided by agency staff, the hospital cost was €115,374. Taken together, the costs associated with primary Emergency Mental Health presentations is €1,331,844. Costs associated with patients who were previously known to MH services were €843,417.

Discussion

Despite an increasing number of dedicated MH beds, demand outweighs availability, and immediate access remains problematic, the default often being a paediatric admission. Adequate funding and appropriate use of these scare and costly resources must be part of national MH policy planning, especially with ongoing planning for the National Children’s’ Hospital.

Introduction

It is recognised that children attending paediatric services have an increased rate of mental health (MH) problems1. Hospital based Mental Health services, interchangeably termed Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Services (PCLS), or Psychological Medicine, exist in the large hospitals, and collaborate with their paediatric colleagues, offering assessment and intervention as required. However, PCLS may also have a role in providing Emergency MH assessments for young people presenting to the Emergency Department (ED), a role independent of their paediatric colleagues. In some cases, these children will need to be admitted to an acute paediatric bed for the management of their mental health illness or psychological distress, awaiting transfer to a child psychiatry specialised bed, or discharge to community services. The profile and costs of these cases are inadequately captured by both HSE CAMHS Annual Reporting System3,4 and the Healthcare Pricing Office (HIPE)2 as they often inadequately record MH referrals. This study explores the costs associated with a cohort of patients presenting to a large paediatric hospital ED, and managed by PCLS, in a one-year period.

Methods

All children with Emergency MH presenting to ED and subsequently admitted for psychiatric assessment over a 12-month period (Jan -Dec 2016) were identified. Costs associated with Length of Stay (LOS) were calculated using the 2016 daily price for a public hospital bed (€1,978, inclusive of pay and non-pay expenses). In 2016, the total hospital budget for nursing staff provided by external agencies and caring for PCLS patients was €404,500 (inclusive of tax, agency fee and VAT). Sociodemographic and summary clinical data were extracted from case notes using a study specific proforma5. Cost comparisons were also generated for 2 other cohorts of patients; patients with an eating disorder who were admitted for medical stabilisation and subsequently managed jointly by paediatrics and child psychiatry (EatD), and patients admitted for medical/surgical reasons (PL), for which a MH consultation was requested by the paediatricians. Ethical exemption status was confirmed. Study data was stored on the hospital’s private and secure network.

Results

Patient Admitted and Reviewed by PCLS:

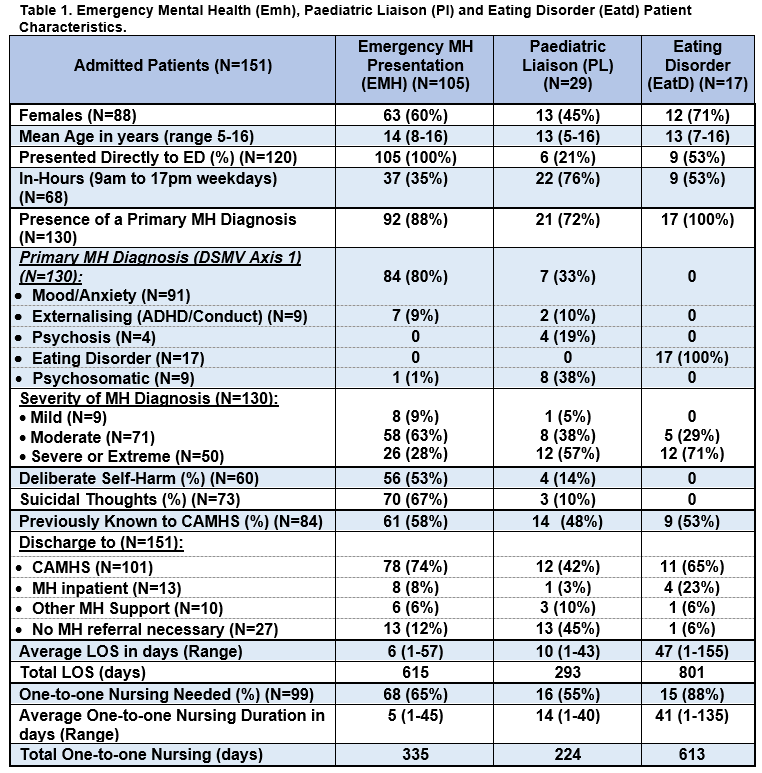

A total of 151 patients reviewed by PCLS were in-patients, with an average age of 13 years (range 5-16), and slightly more females (58%, N=88). Table 1 shows that most presented directly to ED (79%, N=120), most after hours (55%, N=83). The majority had a DSMV axis 1 diagnoses (86%, N=130), most commonly mood/anxiety disorders (60%, N=91). Deliberate self harm was present in almost half (40%, N=60) as was suicidal ideation (48%, N=73). The majority were already known to CAMHS (84, 57%) and had an average LOS of 9 days, shorter than patients’ naive to MH services (average LOS 15 days. (ANOVA F(1)=2.642 p=0.107, 5% level). Clinician severity was most often rated as of moderate severity, (54%, N=71) with a mean LOS of 7 days (1-57). A smaller number (38%, N=50) were classified as severe or extreme, with a mean LOS significantly longer, 22 days (range 1-155); (ANOVA F(2)=9.525 p<0.000, 5% level). Nine individuals were classified as mild, admitted for a mean of two days (1. -6 range)

Patients were divided in three groups. The first group presented with Emergency MH issues (EMH, 70%, N=105), the second was referred by the hospital paediatricians (CL, 19%, N=29) and the third had Eating Disorder diagnoses (EatD, 11%, N=17) (Table 1). The EMH group is studied in more details (Table 1, first column).

Patients with Emergency MH (EMH) Issues:

One hundred and five patients presented via the Emergency Dept with acute MH issues only, and were admitted. One-third were within normal working hours’ (35%, N=37; 9am to 5pm weekdays). More than half (58%, N=61) were previously known to Child and Adolescent Community MH services (CAMHS). Clinical profile is presented in Table 1. The Emergency MH average LOS was 6 days, median 4 days, ranging from a brief admission of one day to 57 days. Total costs associated with MH bed days were 615 days @ €1,978 or €1,216,470.

Sixty-Eight (65%) required one-to-one nursing, either by a family member, ward nursing staff or agency staff. The average length of one-to-one nursing was 5 days, median 3.5 days, ranging from one to 45 days, with a total of 335 days. The daily agency one-to-one nursing rate was €861. Only agency one-to-one nursing was included into the cost calculation, and conservatively estimating 40% agency use gives a total of €115,374 and as such was an underrepresentation of full one-to-one nursing costs.

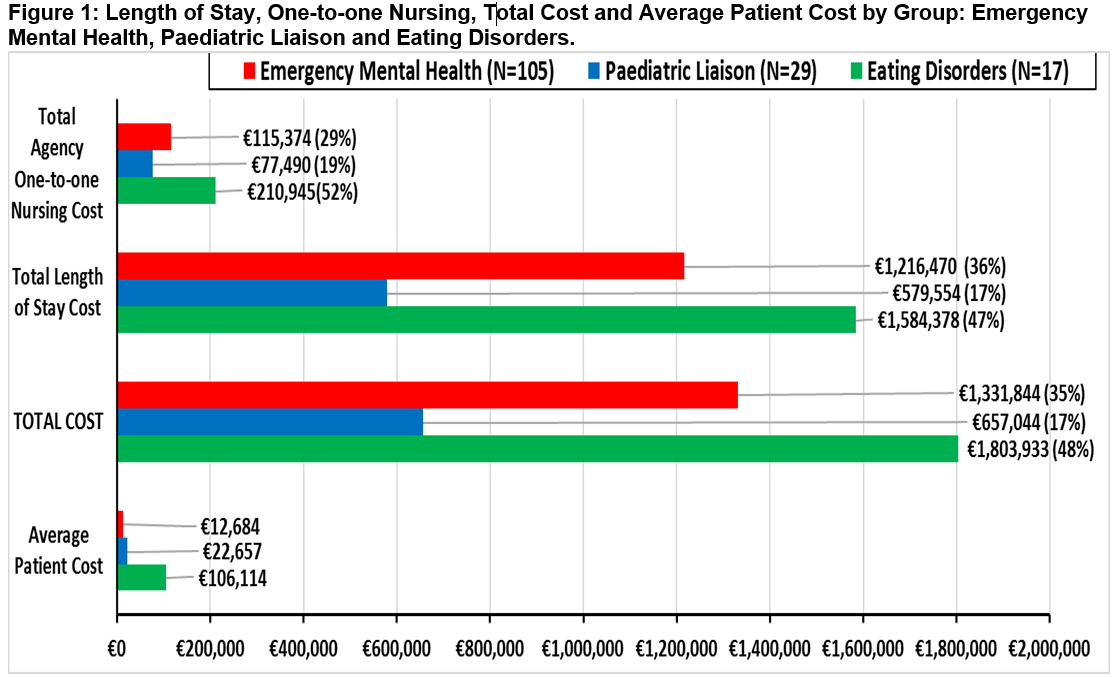

Taken together, the costs associated with Emergency MH presentations for the hospital were €1,331,844 and the average cost per patient €12,684 (Figure 1). The comparison costs for the eating disorder group and the paediatric liaison group are reported in Figure 1.

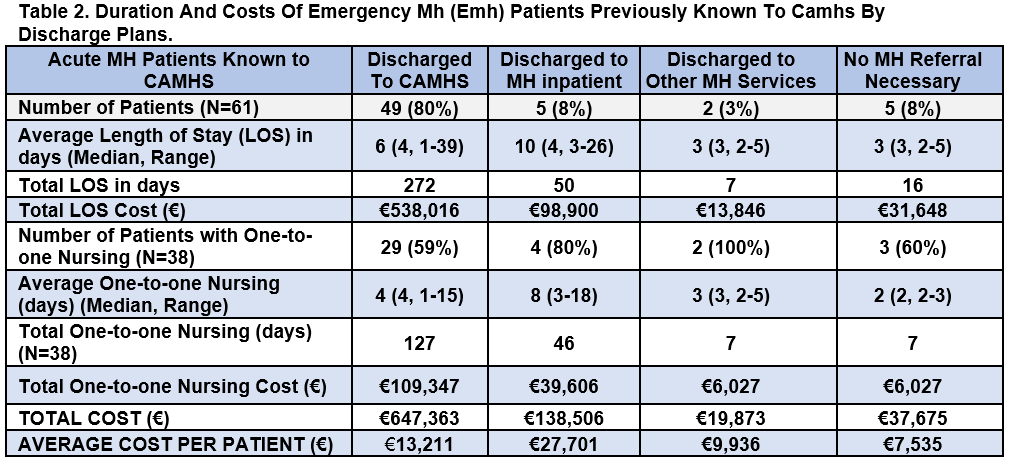

Emergency MH (EMH) Patients Previously Known to CAMHS:

Half of the patients were already known to CAMHS (58%, N=61) and most (80%, N=49) were discharged either back to CAMHS, or other community MH supports such as counselling, or support groups (3%, N=2). The total hospital cost associated with prior CAMHS attendees was €843,417. (Table 2). A small number (8%, N=5) required admission to an in-patient unit with the highest associated per person cost (€27,701) (Table 2). Following assessment by psychiatry, 5 young people were not considered to require any specialised MH follow up and were discharged back to their GP.

Discussion

To-date, there have been no studies focusing on the costs associated with acute mental health presentation to the Paediatric Consultation and Liaison Services in Ireland, as far as the authors are aware. This novel study details the hospital costs associated with PCLS clinical cases in a Dublin paediatric hospital over a 12-month period (2016). The authors have previously presented a poster at the Irish College of Psychiatrists’ Winter Conference 2017, examining all PCLS referrals to the three Dublin paediatric hospitals6. During a one month period, 97 children were assessed, 58 (60%) presenting to the ED, and the majority (36, 62%) admitted. Length of stay, one-to-one nursing or incurred costs were not analysed6. Presented costs are linked with bed days and need for one-to-one Nursing, and do not consider other costs such as medication, time, or MH staffing. There is no dedicated MH budget for the hospital and so this Emergency MH cost of €1,331,844, along with €1,803,933 for the Eating Disorder group, comes from the general hospital funding. The cost of Eating Disorders has been recognised as generally higher than other MH disorders with the acute hospital sector accounting for a substantial share of the expenditure7. This annual cost does not feature on any of the HSE CAMHS data records and is at risk of being unrecognised.

HSE data is available from the 5th Annual CAMHS Report; the last time full clinical details were published. In 2013, there were 60 child psychiatry in-patient beds available, and during a 9-month period, Jan-Sept 2013, 163 young people under 18 were admitted to public beds across 4 units, and 92 to private beds. The average (median) duration of bed days is only available for 2012, and at 52 days (40), is significantly longer that in the paediatric hospital setting, as might be expected.

In the subsequent HSE report for 20154, 261 children were identified as being admitted to one of the four paediatric MH public units (261), with a total bed capacity of 74 beds. Ninety-two children were admitted to adult beds. There is no reference in this report to children admitted to a paediatric setting, hence omitting the 105 children in this audit with acute MH needs, the 17 with eating disorders, and any children admitted to any other paediatric hospital setting. The mean length of stay is not given in the HSE report, but there were 18,936 total bed days used (of which 17,858 were child beds) allowing us to calculate an average (median) stay per patient of 53 days (68). Fewer than 35% of those admitted were under age 16, the age for paediatric care and highlights the fact that the paediatric hospitals are possibly providing a much needed, safe, but unrecognised clinical setting for children in this age group.

The clinical profile of children admitted with Emergency MH concerns suggests that the main reason for referral was for a mood disorder, with either DSH or suicidal ideation. Eleven percent of all admitted cases involved the management of Eating Disorders, almost twice the rate in a UK PCLS audit carried out in the same year8.> This might be accounted for by the fact that MH units in Ireland do not have capacity for provide nasogastric feeding to children with Eating Disorders, hence a medical setting is indicated. The slightly lower rate of females (71%) compared with Irish CAMHS (87%) is consistent with the literature of relatively more boys in the younger age group presenting with an Eating Disorder9. The LOS of our eating disorder cohort was much longer (47) than the other groups8.

HSE summative data is presented for admissions of children (under 18) to child and adult wards (and it is not possible to identify the range for paediatric care separately)4. Admission stays are longer for Eating Disorders (average (median) LOS of 77 (73) days) than Depressive disorders (39 (21) days), similar to findings in the PCLS study. Depressive disorders were the most common reason for admission to public CAMHS in-patient units, again a similar reason for admission in this PCLS (37% cases). Depressive disorders were also the most common MH presentation in Canadian hospitals for 8 to 17-year-olds in 2014-2015 (N=60, 412, 31%)10, and the second most common PCLS diagnoses in 2016 in the UK8 (22%, N=182).

Comparing the clinical profile with a UK PCLS audited in the same year highlights many major differences8. The main reason for referral to UK PCLS services was for assessment and management of psychosomatic problems such as unexplained medical symptoms, encopresis, and treatment adherence difficulties. Only 29% of their work was referred via the Emergency department, compared to the majority of referrals to the Irish PCLS and PCLS in the hospital audited carry out almost no OPD work. Fewer of the cases seen in UK PCLS were previously known to CAMHS (34%) and far fewer discharged back to CAMHS (15%). A previous Irish study reported on 6month PCLS activity, and indicated that the majority of consultations provided by the hospital psychiatry liaison team were to children with acute and severe MH disorders who were indistinguishable from a typical CAMHS cohort5.

The significant number of patients in the Irish study, previously known to CAMHS but still presenting to a new service, suggest a lack of capacity in CAMHS, lack of out of hours service, or a need to be medically assessed following DSH. These patients might be better managed by CAMHS, who have an existing relationship with them, and who have more comprehensive multi-disciplinary teams. Given the PCLS staffing in the hospital is already well below recommended levels, the additional emergency based work has significant repercussions for the availability of PCLS to respond to referrals of medical/surgical inpatients, day patients or outpatients with co-morbid MH issues10. Under-resourcing of both CAMHS and liaison services are recognised in “A Vision for Change”11 but may be contributing to costly hospital admissions for primary MH presentations, and prompting interruption of service, not necessarily in the patients’ best interest.

Furthermore, the PCLS in the study’s hospital setting did not have the recommended MDT with a dedicated social worker, clinical psychologist, or other allied health professionals, lack of which may have contributed to prolonged admission3,11. In the Dublin- based PCLS service with a full MDT, twice as many outpatient referrals were made (36% vs 13%)5. Data from adult liaison services indicate that comprehensive MDT are associated with beneficial effects on health and wellbeing, a reduction in length of hospital stay, and cost savings12. Similar findings are emerging regarding paediatric consultation liaison services (PCLS)8.

In all health care systems, the need to ensure appropriate use of resources leads to cost saving and more effective services for all13. Given the high costs associated with hospital admission, the inappropriate use of acute hospital beds is of relevance to policy-makers, clinicians and indirectly to patients. Although the number of dedicated child psychiatry beds in Ireland has steadily increased, from 16 in 2008 to 74 in 2015, demand continues to exceed availability and temporary closure of 50% beds in one Dublin based unit secondary to staffing problems4,14. Ensuring dedicated MH beds are available for the younger age group (under 16) continue to be problematic, therefore creating a vulnerable group with immediate access only to hospital Emergency departments. The number, range and mix of beds appropriate for future demand needs to be carefully considered. This is especially pertinent with plans for the development of the National Children’s Hospital 20 bedded in-patient CAMHS unit and 8 bedded Eating Disorder unit, to ensure that this caters appropriately for young children who are currently silently accessing expensive paediatric hospital beds15.

Correspondence

Claire Kehoe, Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin.

Email: [email protected]

Conflicts Of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest

References

1. Gomez J. (1987) Liaison Psychiatry: Mental Health Problems in the General Hospital, London: Croom-Helm.

2. Healthcare Pricing Office (HIPE) (2016). Activity in Acute Public Hospitals in Ireland 2015 Annual Report. December 2016.

3. HSE Delivering Specialist Mental Health Services 2014-2015.

https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/Mentalhealth/delivering-specialist-mental-health-services-2014-2015-final.pdf

4. Fifth Annual Report of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) 2012-2013. http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/news/media/pressrel/newsarchive/2014archive/feb14/CAMHSannualreport.html

5. Lynch, F., Kehoe, C., MacMahon, S., McCarra, E., McKenna, R., D'Alton, A. & McNicholas, F. (2017). Paediatric Consultation Liaison Psychiatry Services (PCLPS)-what are they actually doing?. Irish medical journal, 110(10), 652-652.

6. Sheridan G, Abualsaud D, Clifford M, Barrett E, Kehoe C & McNicholas F. Paediatric Consultation Liaison Services, who are they seeing? Poster for the Irish College of Psychiatrists Winter Conference 2017.

7. Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Beghi E, Dodel R, Ekman M, Faravelli C, Fratiglioni L, Gannon B. (2011) Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European neuropsychopharmacology. Oct 1;21(10):718-79.

8. Garralda ME & Karmen Slaveska-Hollis K. (2016) What is special about a Paediatric Liaison Child and Adolescent Mental Health service? Child and Adolescent Mental Health 21, No. 2, 2016, pp. 96–101.

9. Daly A. & Craig S. (2016). Activities of Irish Psychiatric Units and Hospitals 2015 Main Findings. Health Research Board Statistics Series 29.

10. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Patient Cost Estimator, 2014-2015. https://www.cihi.ca/en/patient-cost-estimator.

11. A Vision for Change. Report of the Expert Group on Mental Health Policy. 2006, Health Service Executive.

http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/Mentalhealth/VisionforChange.html

12. Parsonage M. & Fossey M. (2006). Economic evaluation of a liaison psychiatry service. Centre for Mental Health Report 2006.

13. McDonagh MS., Smith DH. & Goddard M. (2000). Measuring appropriate use of acute beds: a systematic review of methods and results. Health policy. 2000 Oct 1;53(3):157-84.

14. Power J. (2017) The Irish Times. May 22, 2017. Half beds at children’s mental health unit to close due to nurse shortage.

15. National Children Hospital, Working Together for our Children. (2017). National Paediatric Hospital Development Board and the Children’s Hospital Group Board welcome Government approval of the construction investment for the new children’s hospital project. June 2017.

(P715)