Interventions to Improve the Treatment of Malaria in an Acute Teaching Hospital in Ireland

O’Connor R1, Morley D2, Relihan E1, Broderick A2, Merry C2, Bergin C2,3

1Pharmacy Dept, St James’s Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland.

2 Department of GU Medicine and Infectious Diseases St James’s Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland.

3Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

Abstract

Malaria is the most serious parasitic infection. At our institution over a two year period there were treatment errors in 18% (n=3) of cases. The aim of this multidisciplinary study was to ensure appropriate and timely treatment of malaria by implementation of a cluster of interventions: reconfiguration of existing guidelines, provision of prescribing information; delivery of education sessions to front-line staff and enabling rapid access to medication. Staff feedback was assessed through a questionnaire. Perceived benefits gained included awareness of guidelines (91%, n= 39), how to diagnose (81%, n =35), how to treat (86%, n=37), that treatment must be prompt (77%, n=33) and where to find treatment out of hours (84%, n=36). ‘Others’ perceived benefits (5% n= 2) noted referred to treatment in pregnancy. Going forward, a programme of on-going staff education, repeated audits of guideline compliance and promotion of reporting of medication errors should help ensure that these benefits are sustained

Introduction

Malaria is the most important vector borne disease in the world1. There are five kinds of malaria that can infect humans, with Plasmodium falciparum being the most severe form of malaria, and it and P. vivax are the most commonly encountered2. It is a public health concern with more than 3 billion people living in areas at risk of malaria transmission in more than 100 countries with the majority of cases occurring in tropical Africa2. The World Health Organization estimates that there were more than 200 million clinical episodes of malaria in 2015, causing more than 400 thousand deaths2. In Ireland there were 81 cases notified in 2015. They have all been associated with overseas travel and immigrants returning from malaria risk areas3.

Early diagnosis and prompt effective treatment of malaria remains a vital component of malaria control and elimination strategies together with rational use of antimalarials and combination antimalarial therapy4. Access to early and effective treatment is vital as uncomplicated falciparum can progress rapidly to severe which is almost always fatal without treatment4. Multidisciplinary teams bring together health-care professionals to plan the management of complex clinical problems5. In St James Hospital, the Infectious Disease team comprises of doctors, pharmacist & clinical nurse specialists who work together closely to improve patient care. As malaria is uncommonly seen in our institution, the aim of this multidisciplinary (pharmacist/doctor) study was to ensure appropriate and timely treatment of malaria by implementation of a cluster of interventions namely to improve existing hospital guidelines, providing prescribing information with medication supply, education sessions with front line staff and ensuring access to treatment at all times.

Methods

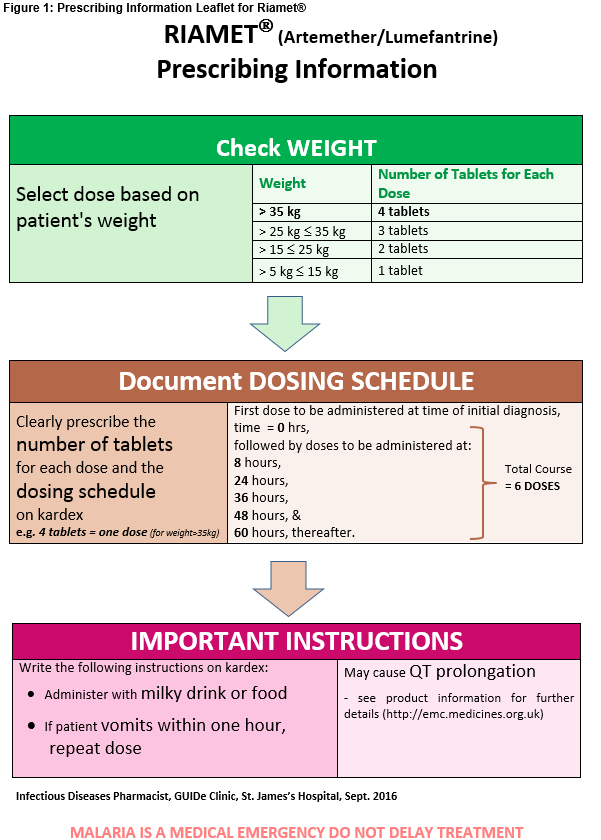

The cases of treatment errors over the past two years were first analysed in detail and then a set of quality improvement interventions were then designed by a multidisciplinary team (doctor/pharmacist) to address all of the contributory factors identified. The existing guidelines for the treatment of malaria were revised in order to update them and to include an algorithm to assist prescribers with appropriate selection of medication6,7. The re-designed guidelines were then added to the hospital’s electronic Prescriber’s Guide and their availability advertised on the intranet homepage in March 2017. An IV guideline for quinine plus a prescribing information leaflet (PIL) for artemether/lumefantrine (Riamet®) (see Figure 1) for distribution with each supply of the medication, were also developed8.

The stock levels of antimalarials in the hospital’s emergency medication stock room were revised to ensure quantities were adequate to meet patient needs out-of-hours and thereby eliminate the risk of delays or missed doses as a result of supply issues. Education sessions incorporating a quiz to reinforce the key points of the revised guidelines were devised and delivered by a multidisciplinary team (Infectious Diseases registrar & pharmacist). The sessions were also used as an opportunity to highlight the newly developed clinician support tools (IV guideline and PIL) and instructions regarding accessing the medication out-of hours and recommendation of prompt referral to the Infectious Disease team. An end-of-presentation staff questionnaire was distributed to determine if the learning outcomes of the education session were achieved.

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 43 respondents. Perceived benefits gained included awareness of guidelines (91%, n= 39), how to diagnose (81%, n =35), how to treat (86%, n=37), that antimalarial treatment must be prompt (77%, n=33) & where to find treatment out of hours (84%, n=36). ‘Others’ perceived benefits (5% n= 2) noted referred to treatment in pregnancy.

Discussion

The detailed analysis of local medication error data relating to the treatment of malaria was an essential first step, both with regard to informing our decision to take a multifaceted approach towards quality improvement and to ensuring that the type of interventions taken were tailored for our hospital. Staff feedback suggests that frontline competence and confidence in the management of malaria has been greatly enhanced at the front-line. Going forward prompt referral to the Infectious Disease team, a programme of ongoing staff education, repeated audits of guideline compliance, and promotion of the reporting of medication near misses and errors should help ensure that these benefits are sustained.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare

Correspondence:

Róisín O’Connor Pharmacy Department St James’s Hospital Dublin 8

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC) Vectorborne Disease Sub-Committee for the HPSC Scientific Advisory Committee. Burden of imported malaria in Ireland. Recommendations for surveillance and prevention [Internet]. HPSC September 2010. [cited 16th August 2017]; Available from http://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/vectorborne/malaria/publications/File,4680,en.pdf.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Malaria [Internet]: World Health Organization; April 2017 [cited 16th August 2017]; Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs391/en/.

3. HPSC Annual Epideimological Report. Epidemiology of malaria in Ireland 2015 [Internet]. HPSC 2015. [cited 16th August 2017]; Available from http://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/vectorborne/malaria/publications/annualreportsonmalaria/File,15887,en.pdf.

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria [Internet]: WHO April 2015 [cited 16th August 2017]; Available at www.who.int

5. Fletcher T, Haider A, Ryall C, Beeching N, Joekes E, Lewthwaite P. The benefits of an infectious disease/radiology multidisciplinary team meeting. Journal of Infection. 2012 65(4):363-365.

6. Lalloo D, Shingadia D, Bell D, Beeching N, Whitty C, Chiodini P. UK malaria treatment guidelines 2016. Journal of Infection. 2016 72:653-649.

7. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The diagnosis and treatment of malaria in pregnancy [Internet]:. 2010. Report No.: Green-top Guideline No 54b. [cited 16th August 2017]; Available from https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_54b.pdf.

8. Summary of Product Characteristics for Riamet. Last updated 05/08/14 [cited 16th February 2017]; Available from https://www.medicines.org.uk/.

(P659)