Introduction of an Oral Fluid Challenge Protocol in the Management of Children with Acute Gastroenteritis: A Regional Hospital Experience.

E Umana 1, A Rana 1, K Maduemem 2, E Moylett 3

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, University Hospital Galway, Ireland

2 Department of Paediatrics, University Hospital Galway, Ireland

3 Academic Department of Paediatrics, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

Abstract

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) remains the ideal first line therapy for acute gastroenteritis (AGE). Our aim was to assess the impact of introducing an Oral Fluid Challenge (OFC) protocol on outcomes such as intravenous fluid use and documentation in our institution. A single centre study with data collected retrospectively pre-implementation (April 2015) of the OFC protocol and post implementation (April 2016). Consecutive sampling of the first 55 patients presenting with GE like symptoms and underwent OFC were recruited. One hundred and ten patients were included in this study with 55 patients per cycle. The rates of IVF use decreased from 22% (12) in cycle one to 18% (10) in cycle two. There was an improvement in documentation by 26% (14) for level of dehydration and 52% (31) for OFC volume from cycle one to two. Overall, the addition of the OFC protocol to the management of patients with uncomplicated AGE would help streamline and improve care.

Introduction

It is estimated that 3.2 million episodes of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) occur each year in Ireland1. A prominent complication of AGE is dehydration, which is the most common reason for Emergency Department (ED) visits in the paediatric population. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of oral rehydration therapy (ORT) for treatment of mild to moderate dehydration2. ORT has been shown to be effective and safe in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate dehydration secondary to AGE when compared with intravenous fluid (IVF) therapy3. ORT is painless, less time consuming and a better physiological replacement when compared to IVF therapy4. Oral Fluid Challenge (OFC) is a recent terminology used to describe rehydration therapy in paediatric ED’s. It can be defined as the administration of ORT over an hour in an ED setting to ascertain a child’s ability to tolerate it at home. Our aim was to assess the impact of introducing an OFC protocol on outcomes such as IVF use and documentation in our ED.

Method

This was a single center study with data collected retrospectively pre-implementation (April 2015) of the OFC protocol (flow chart, clinical form and patient discharge advice leaflet – please see attached supplementary material) and post implementation (April 2016). Consecutive sampling of the first 55 patients presenting with GE like symptoms who underwent OFC were recruited. Data on demographics, presenting complaints, level of dehydration, ondansetron use, OFC documentation and IVF use were obtained using a local proforma. This was adapted from NICE guidelines for AGE and the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCHM) best practice guidance for AGE4,5. Inclusion criteria were patients less than 14 years of age who presented with AGE like illness and underwent OFC. Exclusion was based on alternative cause of vomiting (head injury or trauma), acute abdomen, extra gastrointestinal causes, severe dehydration and capillary blood glucose less than 2.6mmol/L. OFC was considered successful if the patient tolerated 10-20mls/kg over an hour. Patients not tolerating OFC were started on IVF and admitted. Education and training occurred in November and December 2015, for doctors and nurses working in our paediatric ED. This was instituted in the form of lectures and shop floor demonstrations on the newly introduced protocol. Anonymised data were inputted into SPSS for descriptive statistics and chi-squared test was used to determine significance of outcomes.

Results

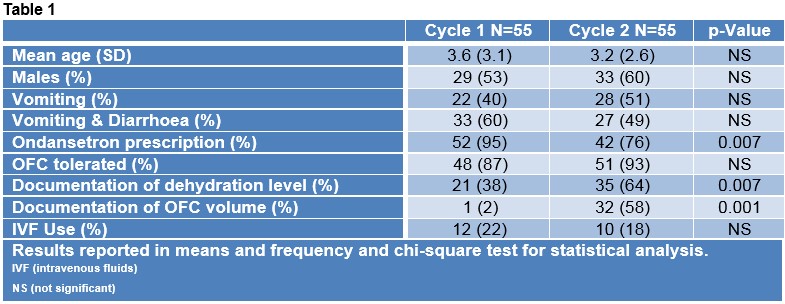

Table 1 compares the demographics, presentations, ondansetron use and outcomes of both cycles. One hundred and ten patients were included in this study with 55 patients per cycle. The rates of IVF use decreased from 22% (12) to 18% (10) in cycle one and two respectively, although not statically significant. There was an improvement in documentation by 26% (14) for level of dehydration and 52% (31) for OFC volume given in cycle one versus two.

Discussion

Our results showed that the implementation of the OFC protocol resulted in more than 20% increase in documentation of dehydration level and OFC volume. There was also a minimal decrease in IVF use (4%). Similar findings were corroborated by Hendrickson et al after the introduction of an ORT protocol which demonstrated a significant increase in documentation of ORT (51% to 100% [p=0.001])6. Their study also noted a significant decrease of 14% in the rates of IVF use6. In AGE, ORT is a proven and effective means to safely and quickly rehydrate children. A recent Cochrane meta-analysis showed ORT to have similar outcomes with IVF rehydration but with decreased length of stay in ED and hospital admission7. In our protocol, ondansetron was only given if the child was actively vomiting in ED or up to 60 minutes prior to arrival. This might have contributed to decreased use of ondansetron; however, this didn’t affect the OFC tolerance. A survey of perceptions regarding ORT use by caregivers in Ireland revealed that most caregivers would prefer IVF as first line therapy8. To tackle such perceptions, the protocol included a discharge leaflet which aimed to educate the caregivers further on ORT use at home. Our protocol thrives on its simplicity of use, thus yielding excellent feedback from the ED staff. Succinctly the advent and implementation of the OFC protocol in the management of patients with uncomplicated AGE would help streamline and improve care in the ED setting.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correspondence

Dr Etimbuk Umana, Department of Emergency Medicine, University Hospital Galway, Galway.

Email: [email protected]

Reference

1. Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre - Northern Ireland, Department of Public Health Medicine and Epidemiology, University College Dublin. Acute Gastroenteritis in Ireland, North and South. A Telephone Survey 2003 [Internet]. [cited 2017Jul10]. Available from: http://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/gastroenteric/gastroenteritisoriid/publications/acutegastroenteritisinirelandnorthandsouth/File,512,en.pdf.

2 NICE2009-06-01T00:00:00 01:00. Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis in under 5s: diagnosis and management [Internet]. Guidelines. 2009 [cited 2017Nov15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/resources/diarrhoea-and-vomiting-caused-by-gastroenteritis-in-under-5s-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-975688889029.

3 Hom J, Sinert R. Comparison Between Oral Versus Intravenous Rehydration to Treat Dehydration in Pediatric Gastroenteritis. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2009;54(1):117–9.

4 Canadian Paediatric Society, Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committee Oral rehydration therapy and early refeeding in the management of childhood gastroenteritis. Paediatr Child Health. 2006;11:527.

5 The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Gastroenteritis updated 2015 [Internet]. [cited 2017Jul10]. Available from: http://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Gastroenteritis/.

6 Hendrickson MA, Zaremba J, Wey AR, Gaillard PR, Kharbanda AB. The Use of a Triage-Based Protocol for Oral Rehydration in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2017;1.

7 Hartling L, Bellemare S, Wiebe N, Russell K, Klassen T, Craig W. Cochrane review: Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal. 2007;2(1):163–218.

8 Maduemem KE, Rizwan M, Akubue N, Maris ID. Perceptions and practices of oral rehydration therapy among caregivers in Cork, Ireland. Int J Community Med Public Health 2017; 4:3536-41.

(P775)