Knowledge of HIV PEP Among Healthcare Workers in Ireland, 2016: Room for Improvement

P Garvey1,2, L Thornton1, F Lyons3

1 Health Protection Surveillance Centre - Health Service Executive, Dublin 1, Ireland

2 European Programme for Intervention Epidemiology Training, European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Stockholm, Sweden

3The Health Service Executive Sexual Health and Crisis Pregnancy Programme, Dublin 1, Ireland

Abstract

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is an important aspect of HIV prevention following potential exposure. We conducted a survey to assess knowledge of HIV PEP, and awareness of HIV PEP resources, among key healthcare professionals, using an anonymous online questionnaire. Twelve (18%) of 68 respondents answered five or more of six knowledge questions correctly; 49 (72%) cited the Emergency Management of Injuries (EMI) toolkit as a resource. Although most respondents were aware of the EMI Toolkit for HIV PEP, the low number of respondents correctly answering knowledge questions suggests a need for training to avoid potential suboptimal HIV PEP use.

Introduction

Injuries where there is an infection risk frequently present to emergency departments (EDs), occupational health (OH) departments and sexual assault treatment units (SATUs). Bloodborne virus infections, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), arising from human bites, needlestick injuries and sexual exposures are of particular concern1,2. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is an important aspect of HIV prevention following such injuries. Irish guidance on HIV PEP was first published in 2012 (and revised in 2014) as part of the Emergency Management of Injuries (EMI) toolkit3. These guidelines are considered national best practice in relation to HIV PEP, and were widely disseminated at the time of publication. In 2016, we conducted a cross-sectional study among key healthcare professionals in Ireland to assess knowledge of HIV PEP, and awareness of resource tools for HIV PEP, in order to identify opportunities for improved awareness/education.

Methods

Eligible survey participants included medical or nursing staff based in EDs, SATUs and OH services within hospitals. We sent invitations initially to key contacts, who cascaded the survey to their professional membership; these included key contacts for the Irish Association of Emergency Medicine, the SATUs, the Irish Emergency Medicine Trainees Association, the HSE Emergency Medicine Programme, the Institute of Occupational Health Physicians, RCPI, and the Occupational Health Nurses Association of Ireland. Respondents completed a self-administered online questionnaire. This included questions about knowledge of HIV PEP, sexual-history taking and awareness of resources for HIV PEP. We evaluated and recoded responses to indicate correctness. We calculated proportions using the total number of non-missing answers as denominator.

Results

We received 68 completed questionnaires; 48 from medical; 20 from nursing professionals. For two service-professional groups with denominators provided by the relevant contacts that cascaded the survey (Emergency Medicine Consultants and Forensic Examiners in SATUs), response proportions were 21% (16/77) and 35% (15/43), respectively.

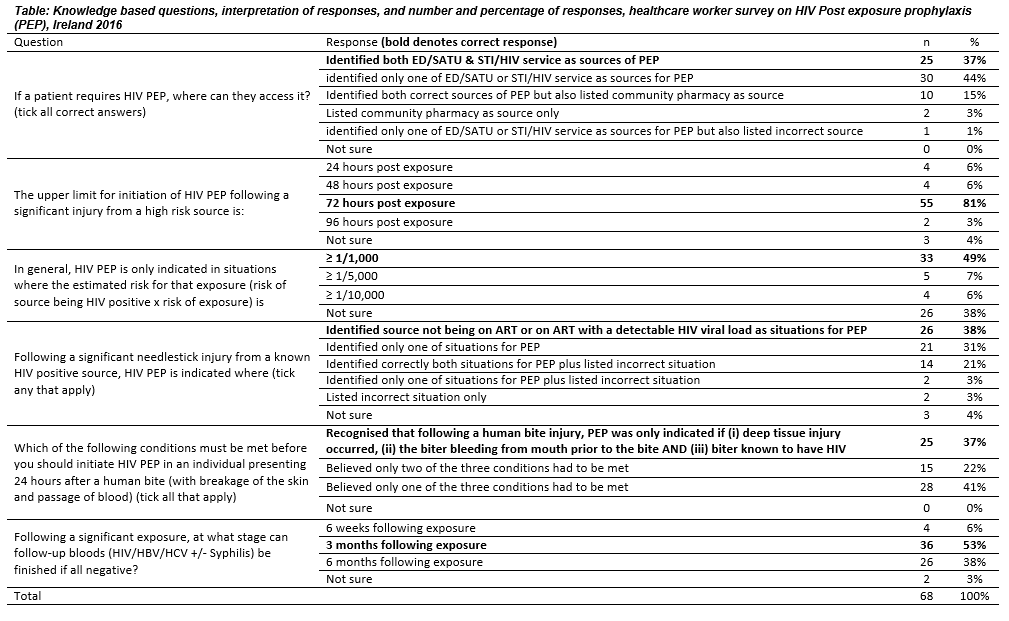

Overall, 12 (18%) respondents answered five or more knowledge questions correctly. Twenty-five (37%) respondents correctly identified both ED/SATU and sexual transmitted infection (STI)/HIV services as sources providing access to HIV PEP (Table). Thirteen (19%) incorrectly identified community pharmacies as a place where HIV PEP prescriptions could be processed. Fifty-five (81%) knew that the upper time limit for initiation of PEP following an injury was 72 hours. Thirty-three (49%) recognised that HIV PEP was only indicated when the estimated risk of exposure was ≥ 1/1,000. Twenty-six (38%) respondents correctly identified the two situations where PEP was indicated following a significant needlestick injury from a known HIV positive source (i.e. the source not on antiretroviral therapy (ART) or the source on ART with a detectable HIV viral load). Twenty-five (37%) respondents knew that, following a human bite, HIV PEP was only indicated if deep tissue injury occurred, the biter was bleeding from their mouth prior to the bite and the biter was known to have HIV infection. Thirty-six (53%) respondents knew that follow-up blood tests could be terminated three months after exposure if all specimens were negative .

Overall, 12 (18%) respondents answered five or more knowledge questions correctly. Twenty-five (37%) respondents correctly identified both ED/SATU and sexual transmitted infection (STI)/HIV services as sources providing access to HIV PEP (Table). Thirteen (19%) incorrectly identified community pharmacies as a place where HIV PEP prescriptions could be processed. Fifty-five (81%) knew that the upper time limit for initiation of PEP following an injury was 72 hours. Thirty-three (49%) recognised that HIV PEP was only indicated when the estimated risk of exposure was ≥ 1/1,000. Twenty-six (38%) respondents correctly identified the two situations where PEP was indicated following a significant needlestick injury from a known HIV positive source (i.e. the source not on antiretroviral therapy (ART) or the source on ART with a detectable HIV viral load). Twenty-five (37%) respondents knew that, following a human bite, HIV PEP was only indicated if deep tissue injury occurred, the biter was bleeding from their mouth prior to the bite and the biter was known to have HIV infection. Thirty-six (53%) respondents knew that follow-up blood tests could be terminated three months after exposure if all specimens were negative .

Regarding sexual history-taking, 53 (79%) of respondents felt comfortable and 49 (73%) felt competent asking questions relating to sexual encounters. Although 31 (47%) respondents received training in sexual history taking, 48 (74%) indicated they would welcome training in this regard; this figure was 95% (19/20) among non-consultant medical professionals.

At 72% (n=49), the EMI toolkit was the resource most frequently cited where respondents learned about HIV PEP; 39 (80%) found it very useful or extremely useful. The toolkit was reportedly comprehensive and easy to use. However, seven respondents (two emergency consultants, one occupational health consultant and four occupational health nurses) suggested that training was needed for the interpretation and practical application of the resources within it.

Discussion

Most respondents were aware of resources for HIV PEP and its application in the management of injuries, in particular the EMI Toolkit. The high proportion of incorrect answers to some questions suggests the potential for missed opportunities to reduce the risk of HIV, creation of unnecessary anxiety among patients attending, inappropriate follow-up plans or inappropriate use of HIV PEP.

A limitation of the study was that due to the snowball sampling and cascade of the questionnaire, it was not possible to estimate the overall response, and for the groups where denominators were available, the response was low. We have attempted to address the low overall number of respondents by providing professional group and service specific analyses where possible.

Through implementation of the National Sexual Health Strategy4, the clinical lead at the HSE sexual health and crisis pregnancy programme will identify and execute mechanisms to provide further training in the interpretation and usage of the resources within the EMI toolkit, and mechanisms to increase knowledge of HIV PEP. Relevant professional groups have been consulted in this regard. Possibilities include presentations at planned study days, a stand-alone EMI training presentation for new doctors and nurses as part of induction, or presentations at national conferences. The provision of training in sexual history-taking will be included. This is currently being delivered through mandatory HST training at RCPI and is due to start for all Emergency Medicine trainees in January 2017.

Correspondence:

Patricia Garvey, Health Protection Surveillance Centre, 25-27 Middle Gardiner Street,

Dublin 1,Ireland,

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Honorary Secretary for the Irish Association of Emergency Medicine, the National Director of SATUs, the President of the Irish Emergency Medicine Trainees Association, the Nurse Lead on the HSE Emergency Medicine Programme, the Institute of Occupational Health Physicians, RCPI, and the Occupational Health Nurses Association of Ireland for their support in dissemination of the survey, and to the individuals who responded to the survey. Patricia Garvey is also grateful for advice received from Dr. Kostas Danis, EPIET co-ordinator, (EPIET-ECDC Sweden & Sante Publique France).

References

1. O’Leary FM, Green TC. Community acquired needlestick injuries in non-health care workers presenting to an urban emergency department. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2003;15:434-40.

2. Richman KM, Rickman LS. The potential for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus through human bites. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993;6:402-6.

3. Health Protection Surveillance Centre. 2012. Guidelines for the Emergency Management of Injuries (including needlestick and sharps injuries, sexual exposure and human bites) where there is a risk of transmission of bloodborne viruses and other infectious diseases. Available at http://www.hpsc.ie/A-Z/EMIToolkit/

4. Department of Health. 2015. National Sexual Health Strategy 2015-2020. Available at http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/National-Sexual-Health-Strategy.pdf.

P502