Management of Bone Fragility in Primary Care in Ireland

R O’Connor, A O’Regan ,J O ‘Doherty

Department of General Practice, Graduate Entry Medical School, University of Limerick, Plassey, Limerick.

Abstract

This study evaluated the prevention of bone fragility fractures in a representative sample of four Irish general practices. The clinical records of 243 patients potentially at risk of bone fragility were studied. One hundred and fourteen (47%) had a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. Osteoporosis was established in 42 (17%) and osteopaenia in 28 (11%). One hundred and fifty-two (63%) were currently being prescribed bisphosphonates. Thirty-four (22%) of those on bisphosphonates did not have a baseline DEXA scan performed prior to commencing treatment and further analysis did not show a clear rationale for initiation of the treatment in this group of patients. Forty-six (30%) patients on bisphosphonates had been prescribed them for over 5 years without any apparent review to see if they were still indicated. There was no record of any of the practices having carried out a fracture risk score assessment prior to commencing bone fragility treatment. The implications are that bone fragility management warrants urgent review.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is characterised by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture, particularly fractures that result from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in fracture, known as fragility fractures1. Osteopaenia is a less severe form of osteoporosis but is also associated with an increased risk of fracture2. The burden of osteoporosis in Ireland is substantial and increasing3, 4. The prevalence of osteoporosis rises markedly with age and it is estimated that approximately 50% of women and 20% of men aged over 50 years’ experience an osteoporosis-related facture at some point in their lifetime5. With an increasingly elderly population this has become an extremely important health issue6.

Risk of fracture is also increased by factors such as lifestyle, drug treatments, family history, and other conditions that cause secondary osteoporosis7, 8. Large randomised controlled trials have shown that bisphosphonate therapy for 3 to 4 years is effective in reducing the risk of both non-vertebral and vertebral fractures in osteoporotic women8.

However, there is considerable controversy over the optimal duration of anti-resorptive therapy, particularly since the reporting of side-effects, including atypical subtrochanteric fractures during long-term bisphosphonate therapy9, 10.

The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool “FRAX” was developed in 2008 to provide a prediction tool for assessing an individual’s risk of fracture in order to provide general clinical guidance for treatment decisions11. It has been adapted to the Irish population using estimates about life expectancy and fracture incidence in Ireland. It is readily calculated at the time of DEXA scan.

Prior to prescribing anti-resorbtive medication for patients, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published recommendations on the process of risk assessment of fragility fractures which should be undertaken1. These have been updated more recently, but their fundamental recommendations regarding initial assessment and prescription of anti-resorbtive medications remain unchanged12. The overarching aim of this study was to determine if the prevention and management of bone fragility fractures in an Irish general practice setting adhere to best practice guidelines. Specific objectives were to review bone strengthening prescriptions including those for bisphosphonates and calcium/vitamin D combinations and to investigate how the risk of bone fragility fractures is being assessed.

Methods

Four practices affiliated with the University of Limerick Graduate Entry Medical School with a senior medical student on general practice placement in 2012/13 participated in this study. The practices were based in two of Ireland’s four healthcare regions (South, West) and are broadly representative of general practices nationally by size, patient eligibility for free medical care and urban/rural location7.

Third year medical students on placement and their general practitioner supervisors used reporting functions of electronic practice management systems to generate a list of all patients who were either on bisphosphonate therapy currently, or were females aged over 65 years and therefore at risk of having osteoporosis or bone fragility. A random sample was then generated using a random number function in Microsoft Excel.

Three practices were fully computerised, one was not. All practices had a full time secretary and practice nurse. Practice 1 was a rural singlehanded and collected data on 86 female patients aged over 65 years. Practice 2 was a rural group and collected data on 50 female patients aged over 65 years. Practice 3 was an urban group and collected data on 47 patients who were already on bisphosphonate therapy. Practice 4 was also an urban group and collected data on 60 patients who were already on bisphosphonate therapy.

Records were then checked for the presence of a fragility fracture risk assessment prior to or during bisphosphonate prescription. The clinical records of a subsample that were prescribed bisphosphonates were studied for documented indications for initial prescription and duration of treatment. The proportion of patients who had a Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan was also studied. DEXA scan results, if present, were analysed in all patients. Osteopaenia was diagnosed when bone mineral density (BMD), as measured by DEXA scanning, was less than one standard deviation (SD) of young adult female reference mean but greater than minus 2.5 SD. Osteoporosis was diagnosed when the DEXA result was less than minus 2.5 SD.

Results

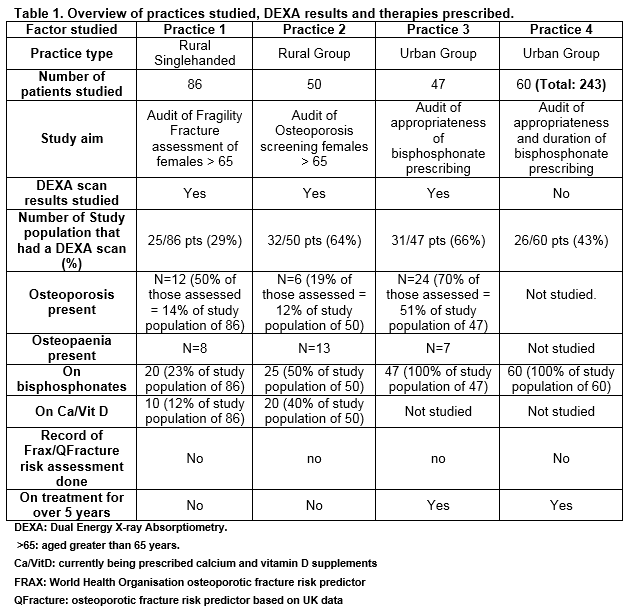

A total of 243 patient records were studied: 136 from the rural practices and 107 from the urban practices. The overall features of the practices studied are summarised in table 1.

DEXA Scan analysis

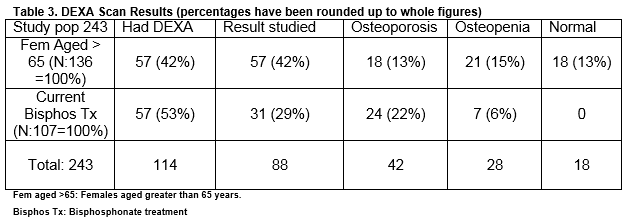

Forty-two percent of the females aged over 65 years studied had had a DEXA scan ever (N=57).

Fifty-three percent of those who were currently being prescribed bisphosphonates had had a DEXA scan ever (N=57). See tables 1 and 2.

The rate of and results of DEXA scanning were analysed in 183 patients in three of the practices studied (75% of the total study population). A total of 114 DEXA scans were taken in this group (47% of the total study population) in the course of the study period.

In this subgroup of 183 patients, osteoporosis was established in 42 patients (17% of the total study population, 23% of the population in which the test result was analysed, and 22% of those who were currently being prescribed bisphosphonates). Osteopaenia was established in a further 28 patients, (11% of the total study population, 15% of the population in which the test result was analysed and 6% of those who were currently being prescribed bisphosphonates). Eighteen DEXA scan results were normal. See table 3.

Bisphosphonate group

Sixty-three percent of total study population (152 patients) were currently being prescribed bisphosphonates. This figure was made up of all of the 107 patients currently on bisphosphonates plus 45 from the group of females aged over 65 years. See tables 2 and 3.

Thirty-three percent of the 136 females aged over 65 years (45 patients) were being prescribed bisphosphonates. This number was greater than all the patients with DEXA diagnosed osteoporosis (13%; N = 18) and osteopaenia (15%; N= 21) combined in this category.

22% of the 136 females aged over 65 years (30 patients) were being prescribed calcium and vitamin D supplements. This parameter was not studied in the study group who were prescribed bisphosphonates. In one practice where 47 patients were on bisphosphonates and where the DEXA results were analysed, osteoporosis was established in 51% (24 patients), and osteopaenia in a further 15% (7 patients). Thus, 34% of patients on bisphosphonates had a normal DEXA scan. Further analysis of these patients’ files showed that these patients had other risk factors for bone fragility: being prescribed on high dose steroids, had rheumatoid disease or x ray changes suggesting reduced bone density. However in another practice studied, 57% (34 patients) of those on bisphosphonates had not had any baseline DEXA scan performed prior to commencing treatment and further analysis did not show a clear rationale for initiation of the treatment. Of those being prescribed bisphosphonates, 30% (46 patients) had been prescribed the drugs for over 5 years without any apparent review to see if they were still required. There was no record of any of the practices having carried out a fracture risk score assessment prior to commencing bisphosphonate therapy.

Discussion

Our study has shown that fracture risk assessment using tools such as FRAX or QFracture did not seem to take place in many patients prior to commencement of bone strengthening treatments in the form of bisphosphonates and or calcium / vitamin D supplementation.

It is possible that such risk assessment may have been done in the practices and no specific record made of the exercise. Many patients prescribed bisphosphonates did not have bone density assessed beforehand. Also 30% of those being prescribed bisphosphonates were taking them for over 5 years without any indication that a review had taken place to consider stopping them or switching to another treatment8.

Whatever the reason they were initiated, our study showed that of the 92 patients being prescribed bisphosphonates where the indication was studied, only 46% (42 patients) had DEXA confirmed osteoporosis. Many of these patients may well have been taking the bisphosphonates with little benefit and potential risk of harm10, 13. Neither was there any indication of the use of non-drug measures, which are also recommended for the building up of bone mass and prevention of fractures14. GPs should also ensure that their patients have an adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, avoiding excessive intake, in line with international guidelines15. It has also been suggested that calcium intake should be estimated at the time of DEXA scanning to guide supplementation needs16.

Traditionally the measure of bone mineral density was used to assess patients’ risk of future fractures17. The development of fracture risk assessment tools (FRAX11 and Q Fracture18) has led to a fundamental shift in the approach to risk assessment. They have become a crucial part of the assessment of patients fracture risk before a decision is made to commence any form of bone strengthening treatment1, 12, 19. A recent population study demonstrated that the prevalence of people at risk of bone fragility is much higher than documented osteoporosis or than the number of people taking bone strengthening medications20.

Our findings are consistent with Ewald’ review of bone fragility prevention and early intervention which showed less than adequate delivery of these in Australian general practice21. Even the NICE guideline on the topic of osteoporosis and assessing the risk of fragility fracture declares that identifying who will benefit from preventative treatment is imprecise1. There appears to be a significant amount of confusion currently in the screening for and treatment of bone fragility in Irish general practice with a view to preventing fractures.

To our knowledge this is the first study carried out of the assessment and management of bone fragility in Irish general practice. It provides an accurate picture of current practice in the detection and management of bone fragility to prevent fractures.

It is important to consider context when analysing studies such this in general practice. GPs are busy clinicians who deal with a variety of problems, one of the most challenging being multi-morbidity22. It is unrealistic to expect GPs to think of and complete all parameters in all conditions in an un-resourced and unstructured work environment. Success has been previously documented in diabetes care when a standardised and resourced approach was introduced23. This could be used as a paradigm for the management of other chronic illnesses such as bone fragility in a community setting.

The strengths of this study are that the data was directly taken from the practice patient records by experienced students and is therefore accurate and not subject to recall bias.

The weaknesses are that not all the data was analysed in a standardised manner. Hence not all the data could be included in this analysis. Future research should involve a larger sample size of GPs, investigating the use of validated fracture risk assessment tools and the factors involved in the decision to commence bone strengthening medication.

Conflict of Interest:

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements:

1 - Professor Ailish Hannigan, Professor of Statistics, Graduate Entry Medical School, University of Limerick, Plassey, Limerick.

2 - Professor Colum Dunne, Director of Research, Graduate Entry Medical School, University of Limerick, Plassey, Limerick.

Correspondence:

Dr Raymond O’Connor, Room GEMS 2-012, Graduate Entry Medical School, University of Limerick, Plassey, Limerick.

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Rabar S, Lau R, O'Flynn N, Li L, Barry P. Risk assessment of fragility fractures: Summary of NICE guidance. BMJ (Online). 2012;345(7869).

2. Masud T, Jordan D, Hosking DJ. Distal forearm fracture history in an older community-dwelling population: the Nottingham Community Osteoporosis (NOCOS) Study. Age and ageing. 2001;30(3):255-8.

3. Hiligsmann M, McGowan B, Bennett K, Barry M, Reginster JY. The clinical and economic burden of poor adherence and persistence with osteoporosis medications in Ireland. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2012;15(5):604-12.

4. McGowan B, Casey MC, Silke C, Whelan B, Bennett K. Hospitalisations for fracture and associated costs between 2000 and 2009 in Ireland: a trend analysis. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2013;24(3):849-57.

5. National Medicines Information Centre. Update on Osteoporosis 2013:[1-4 pp.]. Available from: http://www.stjames.ie/GPsHealthcareProfessionals/Newsletters/NMICBulletins/NMICBulletins2013/NMIC%20Osteoporosis%20with%20refs.pdf.

6. Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. The Lancet.374(9696):1196-208.

7. Kelman A, Lane NE. The management of secondary osteoporosis. Best practice & research Clinical Rheumatology. 2005;19(6):1021-37.

8. Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, Cummings SR, Rosen CJ. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis - For whom and for how long? New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(22):2051-3.

9. Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis - Where do we go from here? New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(22):2048-51.

10. McGreevy C, Williams D. Safety of drugs used in the treatment of osteoporosis. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 2011;2(4):159-72.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. FRAX ® Fracture Risk Assessment Tool University of Sheffield, UK2011 [cited 2017 March 3]. Available from: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9.

12. NICE. Osteoporosis Overview: National Institute For Health and Care Excellence; 2017 [cited 2017 02/03/2017]. Available from: http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/osteoporosis.

13. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d2040.

14. Murphy NM, Carroll P. The effect of physical activity and its interaction with nutrition on bone health. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2003;62(4):829-38.

15. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu R, Gallagher JC, Gallo R, Jones G, Kovacs CS, Mayne ST, Rosen CJ, and Shapses SA . The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(1):53-8.

16. McKenna MJ, McKenna MC, van der Kamp S. Should Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Technologists Estimate Dietary Calcium Intake at the Time of DXA? J Clin Densitom. 2016 Apr-Jun;19(2):171-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.03.003. Epub 2015 Apr 28.

17. Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet (London, England). 2002;359(9321):1929-36.

18. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Derivation and validation of updated QFracture algorithm to predict risk of osteoporotic fracture in primary care in the United Kingdom: Prospective open cohort study. BMJ (Online). 2012;345(7864).

19. Irish Osteoporosis Society. Osteoporosis guidelines for health professionals. Dublin: Irish Osteoporosis Society, 2012.

20. Duncan R, Francis RM, Jagger C, Kingston A, McCloskey E, Collerton J, Robinson L, Kirkwood TB, Birrell F. Magnitude of fragility fracture risk in the very old--are we meeting their needs? The Newcastle 85+ Study. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2015;26(1):123-30.

21. Ewald D. Osteoporosis - prevention and detection in general practice. Australian Family Physician. 2012;41(3):104-8.

22. Fisher RF, Croxson CH, Ashdown HF, Hobbs FR. GP views on strategies to cope with increasing workload: a qualitative interview study. The British Journal of General Practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2017;67(655):e148-e56.

23. Collins MM, O'Sullivan T, Harkins V, Perry IJ. Quality of life and quality of care in patients with diabetes experiencing different models of care. Diabetes care. 2009;32(4):603-5.

P674