Oral Cancer Awareness of Non-Consultant Hospital Doctors in Irish Hospitals

D Shanahan 1 CM Healy 2

1 Medical Intern, AMNCH, Tallaght, Dublin 24, Ireland.

2 Consultant/Senior Lecturer in Oral Medicine, Dublin Dental University Hospital, Trinity

College Dublin,Ireland

Abstract

The incidence of oral cancer is rising in Ireland. The aim of this study is to assess the level of awareness of oral cancer amongst non-consultant hospital doctors (NCHDs) in Ireland, so any knowledge deficits can be identified and addressed. Data was collected by means of an anonymous online questionnaire, which was distributed via a private social media page for NCHDs in Ireland. It was completed by 221 participants, of which over 80% recorded that they do not regularly examine patients’ oral mucosa. Sixty percent were ‘unsure’, and 21%, ‘very unsure’, about diagnosing oral cancer based on clinical appearance. Nor were respondents able to identify confidently the various potential risk factors for oral cancer. Eighty-four percent of NCHDs requested further education on the topic. The response rate of the study was low, and further investigation is required to determine if the findings of this study are representative of the wider NCHD community. The chief recommendation of this paper is to provide more education about oral cancer, at both medical undergraduate and postgraduate levels, and to increase awareness of the condition amongst hospital doctors.

Introduction

The incidence of oral cancer in Ireland is rising, with approximately 233 oral cancer cases diagnosed annually1,2. Over 60 percent of patients who present with oral cancer have regional or distant spread. The five-year survival rate for this illness is 44-51%, depending on the stage of the disease, with an average of 71 deaths per year between 2011 and 2015 in Ireland3,4. The majority of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, affecting the lips, tongue, gingivae, floor of the mouth, palate, vestibule, and/or retromolar area; they are distinct from oropharyngeal cancers which occur further posteriorly and affect the soft palate, base of tongue and tonsils. Other oral malignant neoplasms include malignant melanomas, malignant minor salivary gland tumours, lymphomas, odontogenic tumours, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and metastatic neoplasms (most commonly from breast, lung, gastric, liver and renal cancer)5.

The major risk factors for oral cancer include tobacco and alcohol consumption, the synergistic effects of which have been well documented. Heavy smokers and drinkers 38 times more likely to develop an oral cancer compared to those who abstain from both products. Other aetiological factors include poor diet, and betel quid use (an important risk factor for people from Asian ethnic minorities living in Ireland). Exposure to sunlight, immunosuppression, and tobacco are considered risk factors for lip cancer6. Lesions with malignant potential include erythroplakias, leukoplakias, submucous fibrosis, and oral lichen planus5.

Early detection of oral cancer reduces morbidities, and improves survival rates7. Despite considerable efforts to educate the public about this disease – through national events such as ‘Mouth Cancer Awareness Day’ – there continues to be a delay in the presentation of patients seeking professional advice with oral cancer8,9. While general medical practitioners have been shown to refer suspected oral cancers to specialist centres in a timely manner, patients deemed to be at ‘high risk’ of developing these conditions (older, male, heavy tobacco and alcohol users, with a poor diet) are often irregular dental attendees. They are, however, likely to attend hospitals with co-morbidities, and so it is important that hospital doctors are aware of the both the risk factors and signs for oral cancer10. As yet, there have been no studies on referral patterns by hospital-based doctors7.

The aim of this study is to assess the quality of NCHDs’ knowledge of oral cancer, so that we are in a better position to provide education tailored to the particular needs of these professionals. The long-term goal is to promote awareness of the risk factors and presentation of oral cancer, to aid early diagnosis, thereby optimising patients’ chances of successful treatment and survival.

Methods

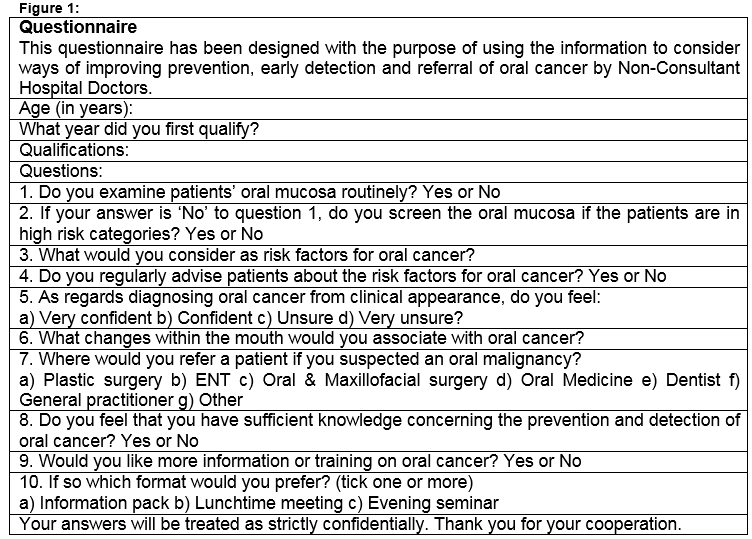

The questionnaire used in this study is shown in Figure 1, and is based on the one used by Carter and Ogden in 200711, which assessed oral cancer awareness of general medical (GMP) and dental practitioners (GDP) in Tayside, United Kingdom. This questionnaire was used to facilitate comparisons with other health professionals. Questions related to the following areas: oral mucosa examination habits, understanding of oral cancer risk factors, confidence in diagnosing an oral cancer, onward referral of suspected oral cancers, sufficiency of knowledge on oral cancer prevention and diagnosis, and the desire for further education on oral cancer.

The questionnaire was developed using the online cloud-based software service, Survey Monkey (CA, United States, http://www.surveymonkey.net), and circulated on a private social media forum for NCHDs working in Ireland. The number of NCHDs who had access to the questionnaire was approximately 4,300. A follow-up reminder was posted on the social media page two weeks later, and the survey remained open for a total of four weeks (July 2016). Non-identifying demographic information was collected. Direct quotations from the free text sections of the questionnaire were recorded and categorized. Frequencies were used to describe demographics, and associations were examined using Chi-Squared Tests. Results were considered significant at P<0.05

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 221 NCHDs working in general medical hospitals in Ireland in July 2016. The response rate was 5.2%. Of those who responded, 142 were women, and 77 were men. Seventy-one percent of respondents were aged between 19 and 29, with 77% having graduated from medical school between 2012 and 2015. Twelve percent of NCHDs were Members of the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland (MRCPI), while three percent had obtained Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (MRCSI).

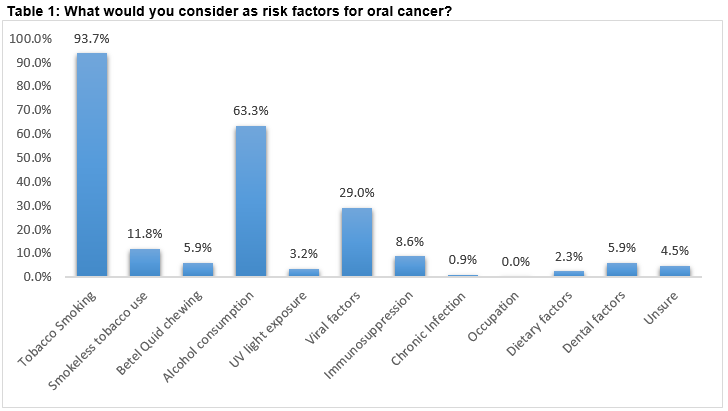

Eighty-one percent of NCHDs testified that they do not routinely examine the oral mucosa of patients, with no significant difference between male and female doctors (x2 1.5356. p-value 0.21). Those with MRCPI/MRCSI qualifications were more likely to examine the oral cavities of their patients (x2=6.3088. p-value is 0.012). One quarter of all doctors said they would only examine a patient if he or she was deemed to be at ‘high risk’ of developing oral cancer. Knowledge of risk factors for oral cancer was posed as an open question; a wide range of responses were generated, shown in Table 1. The three most frequently identified risk factors were tobacco smoking (94%), alcohol consumption (63%), and viral factors (29%).

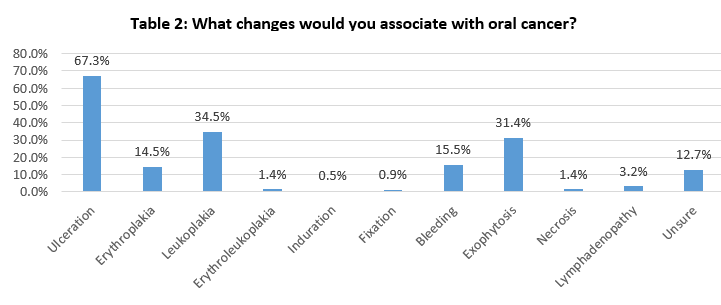

Only 5% of doctors informed their patients of the risk factors associated with oral cancer. NCHDs felt either ‘unsure’ (60%) or ‘very unsure’ (21%) about diagnosing oral cancer based on clinical appearance. Another open question was used to investigate doctors’ knowledge of the changes that they would associate with oral cancer. The answers, listed in Table 2, included ulceration (67%), leukoplakia (35%), exophytosis (31%), and erythroplakia (15%). Significantly fewer NCHDs identified erythroleukoplakia as an important change (one percent). The majority of NCHDs indicated that they would refer suspected oral cancers to either Ear, Nose and Throat surgeons (53%), or Oral and Maxillofacial surgeons (42%). Referrals to Oral Medicine were low at two percent. Only 14% of NCHDs felt that they had sufficient knowledge to detect an oral cancer, with 84% requesting further education on the subject.

Discussion

Oral cancer, and its subsequent management, is physically and psychologically debilitating: it adversely affects the quality of patients’ lives, and is associated with high rates of mortality12. Unfortunately, the majority of oral cancer patients present late, which reduces the opportunities for successful treatment and survival. In their daily practice, medical doctors are more likely to see older patients, and those at increased risk of oral cancer13. Yet only 25% of NCHDs examine the oral mucosa of these high-risk patients, a figure which contrasts unfavourably with the results of the 2007 study of UK GDPs (99%) and GMPs (35%)11. The reason for this low rate of examination seems to be a lack of knowledge, experience, and confidence in recognising significant oral mucosa changes amongst NCHDs14. There may also be a perception among medical doctors that the oral cavity, though readily accessible for examination, is somehow separate from the rest of the body, the territory of the dental profession, and unworthy of their serious consideration.

Regarding risk factors for oral cancer, this study reveals that while tobacco-smoking is well recognised amongst NCHDs, alcohol consumption is less so, with almost a third of respondents omitting it from their list of risk factors. Similar results have been reported in other studies – for example, awareness of alcohol as a risk factor amongst GMPs is 43-51%11,15. The majority of NCHDs were unaware of various other risk factors, including smokeless tobacco (12%), immunosuppression (9%), dietary factors (two percent), and UV light exposure (3%). This final risk factor is particularly associated with lip cancer, a malignancy that some doctors may not even realise is a form of oral cancer. Human papilloma virus (HPV) is a risk factor for oro-pharyngeal cancer, but not for oral cancer; respondents seemed unaware of this distinction, incorrectly identifying HPV as a risk factor for oral cancer (29%)6. These inaccuracies highlight the confusion amongst doctors surrounding the anatomical boundaries of the oral cavity and the shared and differing risk factors for both oral and orophargyngeal cancers16.

Of those NCHDs who were aware of certain risk factors for developing oral cancer, only 5% went on to advise their patients about this. Surely this is a missed opportunity, especially given that smoking and alcohol are important risk factors for many other pathologies, such as coronary artery disease, vascular disease, stroke, and a variety of other malignancies. The above findings, roughly consistent with other studies, attest that there is a vital need to provide more information to medical doctors on the risk factors for oral cancer, particularly the effects of alcohol on the oral mucosa11,14,17.

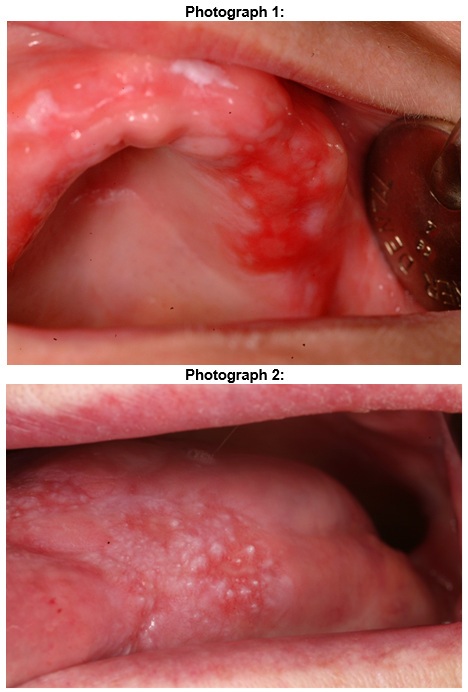

In terms of diagnosis, NCHDs felt either ‘unsure’ (60%) or ‘very unsure’ (21%) about diagnosing oral cancer based on clinical appearance. This is most likely due to a lack of clinical exposure to oral cancer and potentially malignant oral disease at both an undergraduate and postgraduate level.18As in other studies, respondents believed that the primary clinical changes in oral cancer patients were ulceration, leukoplakia, and exophytosis11. By contrast, erythroplakia (Photograph 1) (15%) and erythroleukoplakia (Photograph 2) (one percent) were less commonly cited, despite the fact that they are more likely than a leukoplakia to harbour a squamous cell carcinoma19. These results point to the need to educate NCHDs about the clinical appearance of oral cancers20.

Regarding referral, most NCHDs pass on any suspected lesions to either ENT (53%) or Oral and Maxillofacial surgeons (42%). The higher frequency of referrals to ENT can be attributed to the presence of ENT departments in most general hospitals. Conversely, the low referral rate to Oral Medicine departments (two percent) probably reflects the fact that there are only two Oral Medicine units in the country, and a lack of awareness of these units amongst the medical profession. A contributing factor may be the physical isolation of oral medicine– it is based in dental hospitals, where there is less scope for interaction with the main medical hospital community.

A significant limitation of this study is the low response rate, which means that it does not represent the level of knowledge of the majority of NCHDs in Ireland. Most of the respondents had graduated in the last four years. These individuals are more likely to use social media - the medium through which the questionnaire was distributed - than more senior, older doctors. Nevertheless, this preponderance does provide insights into current undergraduate teaching on oral cancer. It is hoped that further, comparative studies will be conducted to assess the level of oral cancer awareness amongst more senior NCHDs, consultants and other medical professionals.

The study demonstrates that the majority of NCHD respondents (86%) feel that they do not have sufficient knowledge pertaining to the prevention and detection of oral cancers, a trend also visible amongst GMPs11,14,15. To rectify this deficiency, it would be beneficial to include oral cancers in medical undergraduate curricula, and to expand students’ clinical exposure to oral mucosal lesions. In addition, they should be taught to incorporate a thorough oral examination into every general physical examination. Although it is not expected that medical doctors should be proficient at diagnosing oral mucosal disease, the ability to distinguish between normal oral mucosa and oral cancers/oral disease with malignant potential is a realistic goal. Such measures would help redress the entrenched, though receding, perception that the mouth is somehow separate from the rest of the body.

Once qualified, Oral and Maxillofacial surgeons, ENT surgeons and Oral Medicine consultants, could provide further education opportunities to NCHDs. Given that 84% of responding NCHDs requested further teaching on oral cancer, we can be confident that there would be appetite for this training. While the majority of oral cancers will be detected by GDPs and GMPs, an important role can be played by NCHDs in the examination and education of patients, especially those of older age, who present more frequently in acute hospitals, and who are less likely to visit the dentist regularly due to being edentulous21.

The above measures are vital given the great disparity between the five-year survival rates of stage I and IV oral cancer: in Stage 1, where the cancer is localized and under 2cm in size, the rate is 86 percent. By contrast, in stage IV, where the cancer has invaded adjacent structures, or metastasised to lymph nodes or distant structures, survival is only 12-16%22,23. The timely diagnosis of oral cancer can thus have a significant impact both the quality, and length, of patients’ lives.

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author:

Dr Daire Shanahan, SpR/NIHR ACF in Oral Medicine, Department of Oral Medicine, Bristol Dental Hospital, Lower Maudlin St, Bristol BS1 2LY

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +44 (0) 117 34 29641

References

1. McDevitt J, Walsh P. Cancer in Ireland 1994-2013: Annual report of the national Cancer Registry. 2015. http://www.ncri.ie/sites/ncri/files/pubs/NCRReport_2015_final11122015.pdf Accessed 01 June 2017.

2. Ali H, Sinnott SJ, Corcoran P, Deady S, Sharp L, Kabir Z. Oral cancer incidence and survival rates in the Republic of Ireland, 1994-2009. BMC cancer. 2016 Dec 20;16(1):950.

3. Central Statistics Office (CSO0, Ireland. Deaths occurring by sex,cause of death, age at death and year. 2014.

http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=VSA08&PLanguage=0. Accessed 01 June 2017.

4. Howlader N., Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL,Yu M, Ruhl J. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013, National Cancer Institute. [Updated 2016 April, cited 2016 August 19th]Available from

http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/browse_csr.php?sectionSEL=20&pageSEL=sect_20_table.09.html

5. Scully C, Porter S. Oral cancer. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2000 Jul 8;321(7253):97.

6. Warnakulasuriya S. Causes of oral cancer-an appraisal of controversies. British dental journal. 2009 Nov 28;207(10):471.

7. Hollows P, McAndrew PG, Perini MG. Oral medicine: Delays in the referral and treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma. British Dental Journal. 2000 Mar 11;188(5):262-5.

8. Nunn J, Healy CM, Stassen LF, Gorman MT, Martin B, Toner M, Clarke M, Dougall A, Mcloughlin J, Kelly A. Outcomes from the first mouth cancer awareness and clinical check-up day in the Dublin Dental University Hospital. Journal of the Irish Dental Association. 2012;58(2):101-8.

9. McLeod NM, Saeed NR, Ali EA. Oral cancer: delays in referral and diagnosis persist. British dental journal. 2005 Jun 11;198(11):681-4.

10. Ford PJ, Farah CS. Early detection and diagnosis of oral cancer: strategies for improvement. Journal of Cancer Policy. 2013 Jun 30;1(1):e2-7.

11. Carter LM, Ogden GR. Oral cancer awareness of general medical and general dental practitioners. British dental journal. 2007 Sep 8;203(5):E10.

12. Rogers SN, Humphris G, Lowe D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. The impact of surgery for oral cancer on quality of life as measured by the Medical Outcomes Short Form 36. Oral oncology. 1998 May 31;34(3):171-9

13. Goodman HS, Yellowitz JA, Horowitz AM. Oral cancer prevention. The role of family practitioners.Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(7):628-36.

14. Macpherson LM, McCann MF, Gibson J, Binnie VI, Stephen KW. The role of primary healthcare professionals in oral cancer prevention and detection. British dental journal. 2003 Sep 13;195(5):277-81.

15. Riordain RN, McCreary C. Oral cancer–Current knowledge, practices and implications for training among an Irish general medical practitioner cohort. Oral oncology. 2009 Nov 30;45(11):958-62.

16. Tapia JL, Goldberg LJ. The challenges of defining oral cancer: Analysis of an ontological approach. Head and neck pathology. 2011 Dec 1;5(4):376-84

17. Greenwood M, Lowry RJ. Oral cancer: Primary care clinicians' knowledge of oral cancer: a study of dentists and doctors in the North East of England. British dental journal. 2001 Nov 10;191(9):510-2.

18. Hassona Y, Scully C, Shahin A, Maayta W, Sawair F. Factors influencing early detection of oral cancer by primary health-care professionals. Journal of Cancer Education. 2016 Jun 1;31(2):285-91.

19. Bouquot JE, Ephros H. Erythroplakia: the dangerous red mucosa. Practical periodontics and aesthetic dentistry: PPAD. 1995 Aug;7(6):59-67.

20. McCann PJ, Sweeney MP, Gibson J, Bagg J. Training in oral disease, diagnosis and treatment for medical students and doctors in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2005 Feb 28;43(1):61-4.

21. Shanahan D, O’Neill D. Barriers to dental attendance in older patients. Irish Medical Journal. 2017 Apr 1.

22. Vokes EE, Weichselbaum RR, Lippman SM, Hong WK. Head and neck cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993 Jan 21;328(3):184-94.

23. Kerdpon D, Sriplung H. Factors related to delay in diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma in southern Thailand. Oral oncology. 2001 Feb 28;37(2):127-31

P667