Outcomes of a Clinical Leadership Training Program Amongst Hospital Doctors

Kelly D, McErlean S, Naff K

Department of Medicine and Medical Oncology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Eccles St., Dublin 7, Ireland

Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the effectiveness of formal leadership training amongst medical trainees and to review the current literature in this area.

Methods

A literature review of all PubMed cited articles on Physician Leadership from November 2015 to July 2017 was undertaken. Twenty exemplary articles on physician leadership were identified. Fifteen out of 20 were surveys, several of which included a qualitative component, Two out of 20 were cross-sectional analysis and 3/20 involved structured interviews. Overall findings showed that, formalised teaching of leadership tools is associated with improvements in emotional intelligence, self-confidence, and enhanced relationships with colleagues. In addition, having undergone such training, Doctors had an increased ability to manage conflict, conduct meetings and direct groups. The Non-Consultant Hospital Doctor (NCHD) Committee in The Mater Misericordiae University Hospital (MMUH) identified a need for additional leadership and managerial training to support their current role within the Health Service Executive (HSE). The committee devised an educational lecture series in collaboration with leaders in healthcare, business and management. Verbal and written feedback was collected in the form of an end of course survey and attendance was documented.

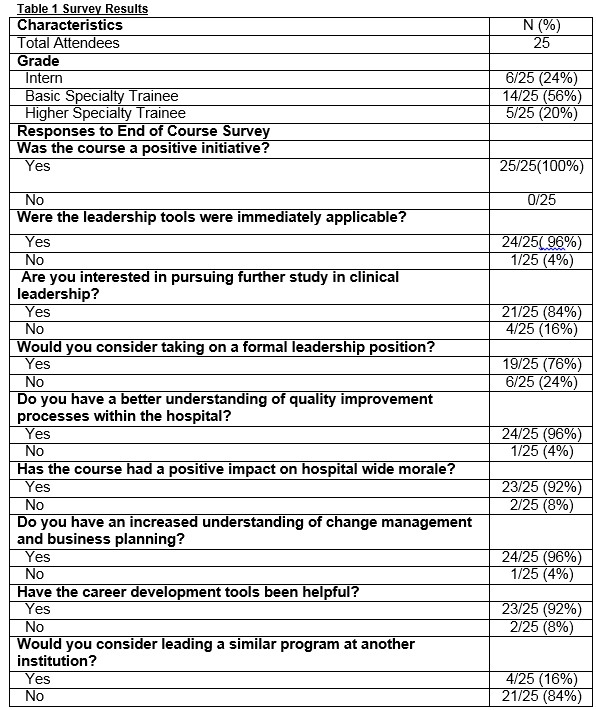

Results

Twenty-five NCHDs attended the Clinical Leadership Programme in MMUH. Fifty-two percent (52%) attended all 5 lectures. Twenty-eight percent (28%) of attendees were male and 72% were female. Eighty percent (80%) were basic specialist trainees or interns and 20% were registrars or higher medical trainees. All participants found the leadership course to be a positive learning experience and reported improvements in leadership skills, management, business planning, career development and quality improvement. Eighty-four percent (84%) were interested in furthering their study in clinical leadership. Ninety-two percent (92%) of participants noted an improvement in hospital wide morale amongst NCHDs following the course.

Discussion

This series could be replicated in other hospitals throughout the HSE and represents one solution to deliver clinical leadership and management training to NCHDs

Introduction

Healthcare organisations are dynamic and represent a complex management system. Clinicians have a unique understanding of the healthcare system and its future challenges. As such, clinician leaders are well placed to create a vision for change, embrace all stakeholders, pursue execution and recognise progress.Current supports for developing physician leaders are minimal. Major reviews of medical education systems around the world have identified leadership as a significant force for positive change and as being crucial to healthcare improvement1. As such, it is critical that we begin to provide structures that enable us to create physician leaders with the tools for ongoing effective improvement.

The primary objective of our program was to provide a teaching schedule to support the professional development of NCHDs and in particular to meet their needs as clinical leaders and managers. The secondary objectives were to facilitate quality improvement initiatives and to increase awareness around management issues and leadership resources. A subsequent literature review of all PubMed cited articles on Physician Leadership from November 2015 to July 2017 was undertaken. Articles published in English were included

Methods

The NCHD body identified a need for additional leadership and managerial training. The NCHD committee devised an educational lecture series. Key leaders in both the medical and business communities were contacted for their expert input, and the NCHD committee engaged directly with the NCHD body to identify their needs. This course was run over a five-week period and attendees received certificates for 100% attendance. Areas addressed included; strategic engagement, innovation in healthcare, global healthcare systems, resilience, career development, self-branding, employment contracts, quality improvement, change management, communication, conflict resolution, negotiation, and business planning. Verbal and written feedback was collected in the form of an end of course survey and attendance was documented (Figure 1).

Results

In total, 25 NCHDs attended the Clinical Leadership Programme. Fifty two percent (52%) attended all 5 lectures. Thirty percent (30%) of attendees were male and 70% were female. Eighty percent (80%) were basic specialist trainees or interns and 20% were registrars or higher medical trainees. The survey results demonstrate that all participants found the leadership course to be a good learning experience and many participants found it to be effective. Attendees reported improvement in leadership skills, management, business planning, career development and quality improvement. The majority of respondents were interested in further study in the area of clinical leadership and many reported improved hospital wide moral amongst NCHDs following the course. (Table 1). Feedback also included suggestions on how to maintain and improve the programme.

Participants reported improved morale, better engagement with management and a greater awareness of quality improvement. This was evidenced by a growing NCHD committee and substantial participation in hospital-wide change initiatives. From the course participants, two joined the NCHD committee and three went on to pursue a Professional Certificate in Healthcare Management.

Discussion

The literature review identified 20 exemplary articles on physician leadership. Fifteen out of 20 were surveys and several included a qualitative component. Two out of 20 were cross-sectional analysis and three out of 20 involved structured interviews. The overall findings were that doctors, regardless of their organizational role, their status or title, self-identify first and foremost as clinicians2. In addition, formalised teaching of leadership tools is associated with improvements in both emotional intelligence and key leadership skills3,4. Leadership training has been shown to improve self-confidence, relationships with colleagues, ability to manage conflict, and ability to conduct meetings and lead groups5.

Many trainees identify the importance of leadership training and often there is a discrepancy between trainees’ needs versus program provisions6. Only 33% of Higher Specialty Acute Internal Medicine UK trainees expect to get dedicated leadership and/or management training during their programme7. In addition, amongst some physicians there appear to be barriers to taking on additional leadership responsibility. These include the belief that physician leaders lack managerial and clinical credibility, have confused identities and multiple leadership roles. Also there are fears that that they may be in conflict with other clinician colleagues and that colleagues lack insight into the complexities of medical leadership8. Lack of financial incentives for additional time spent on management is also an issue for many9.

In 2015, women accounted for 13% (137/1018) of department leaders at the top 50 NIH funded medical schools in the US10. It appears that women place a premium on family contribution, satisfaction outside of work, and a collaborative working environment and may exclude themselves from leadership positions. Obstacles to female physician leadership include perceived lack of support and limited knowledge of organizational leadershi11.

Factors associated with willingness to take on leadership roles include younger age, pursuit of professional development opportunities, a history of leadership training and a perception that mentorship is important for one's current role12. Previous research on clinical leadership has found that physician leaders work in a broad variety of settings and take on multiple leadership roles. They put in time beyond what they are compensated for and indeed many receive no financial support for their formal leadership role. Physicians working in medical specialties spend the most amount of time on leadership activities and least amount of time is provided by physicians in surgical specialties9.

A common motivating theme amongst physician leaders is the capacity to create change. One large Canadian qualitative study identified this as central to the job satisfaction for some physician leaders e.g9.

“In a senior leadership role, you really can think long term, be very strategic, and make big things happen”

“Being in the right place at the right table to discuss these things and bring them forward is what keeps me here”

“I’ll make my voice heard, because my voice is the one for those who cannot speak. That is worth it. That is worth the evenings and the weekends”.

It appears that having a broad sphere of influence in terms of impacting policies, organizational decision-making, leading initiatives, relationship-building and being able to actively make a difference is a strong driver for many physician leaders9. As healthcare management becomes increasingly complex, physician leaders offer a unique insight into health-care system and the many challenges they face. As such, emphasis needs to be placed on supporting physicians in this task. This can be achieved by developing clinicians as leaders, by giving them responsibility over patient care pathways, service planning, and budgeting and utilizing comprehensive performance measurement systems.

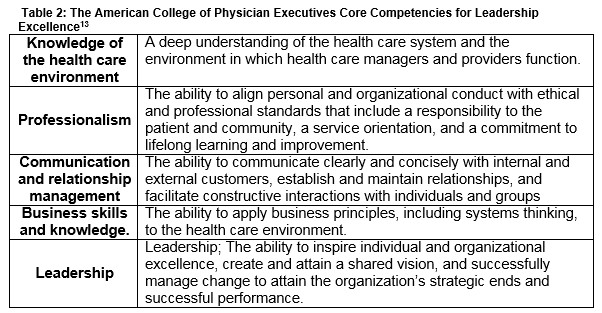

Currently 5% of hospital leaders are physicians13. This is set to increase rapidly as the health system moves toward value-based care2. Perspectives of physicians are increasingly being incorporated in healthcare management. The American College of Physician Executives includes physician leadership as an essential element required to provide optimal patient centred care and describes the core competencies for leadership excellence (Table 2).

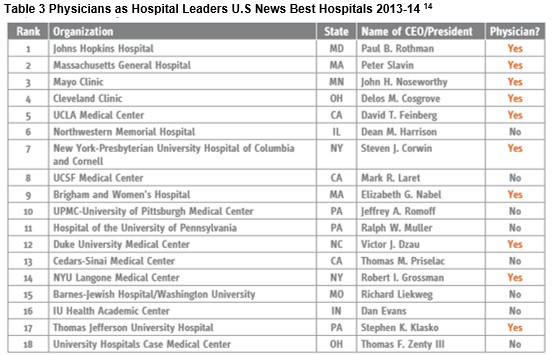

Evidence suggests that organizations and patients benefit when physicians take on leadership roles and that the best-performing hospitals are physician-led. In 2013 the top 5 World Report ranking hospitals were led by physicians, and 10 of the top 18 were physician-led (Table3)14. In the areas of oncology, gastroenterology and cardiology there is a strong positive association between the ranked quality of a hospital and whether the CEO is a physician or not (p < 0.001)15.

In order to sustain the ongoing pursuit of excellence within our healthcare organisations it is evident that there needs to be clear leadership development strategies in place which support protected leadership training and encourage innovation through quality improvement, collaboration and physician engagement strategies9.

This leadership series represents one solution to deliver clinical leadership and management training to NCHDs which is an important recommendation of the MacCraith Report (Section 5.3)16. It could be reproduced in other hospitals throughout the HSE and formalised into NCHD training schemes. It is possible that through on-going education, a national network of clinical leaders could be established that could collaborate, to create better outcomes for patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of Interest to declare

Correspondence

Deirdre Kelly, Department of Oncology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Eccles St. Dublin 7, Ireland.

E-mail: [email protected]

References

1. Ming-Ka Chan , Diane de Camps Meschino , Deepak Dath , Jamiu Busari , Jordan David Bohnen , Lindy Michelle Samson , Anne Matlow , Melchor Sánchez-Mendiola , (2016) "Collaborating internationally on physician leadership development: why now?", Leadership in Health Services, Vol. 29 Iss: 3, pp.231 – 239)

2. Shanafelt T, Swensen SLeadership and Physician Burnout: Using the Annual Review to Reduce Burnout and Promote EngagementShanafelt T, Swensen S. Am J Med Qual. 2017 Feb 1:1062860617691605. doi: 10.1177/1062860617691605.

3. Cerrone SA, Adelman P, Akbar S, Yacht AC, Fornari A.Using Objective Structured Teaching Encounters (OSTEs) to prepare chief residents to be emotionally intelligent leaders. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1320186. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1320186.

4. Gregg SC, Heffernan DS, Connolly MD, Stephen AH, Lueckel SN, Harrington DT, Machan JT, Adams CA Jr, Cioffi WG Teaching Leadership in Trauma Resuscitation: Immediate Feedback from a Real-Time, Competency-Based Evaluation Tool Shows Long-Term Improvement in Resident PerformanceJ Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Aug 3.

5. Experiential Leadership Training for Pediatric Chief Residents: Impact on Individuals and Organizations. Journal of Graduate Medical Education: June 2010, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 300-305)

6. Danilewitz M, McLean L.A landscape analysis of leadership training in postgraduate medical education training programs at the University of Ottawa. Can Med Educ J. 2016 Oct 18;7(2):e32-e50. eCollection 2016 Oct.

7. Smallwood N, Krishnamoorthy S Acute Internal Medicine Trainee Survey 2016. Acute Med. 2016;15(2):93-7.

8. Loh E, Morris J, Thomas L, Bismark MM, Phelps G, Dickinson H.Shining the light on the dark side of medical leadership - a qualitative study in Australia. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). 2016 Jul 4;29(3):313-30. doi: 10.1108/LHS-12-2015-0044.

9. Snell AJ, Dickson G, Wirtzfeld D, Van Aerde J. In their own words: describing Canadian physician leadership. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). 2016 Jul 4;29(3):264-81. doi: 10.1108/LHS-12-2015-0045.

10. Wehner MR, Nead KT, Linos K, Linos E.Plenty of moustaches but not enough women: cross sectional study of medical leaders. BMJ. 2015 Dec 16;351:h6311. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6311.

11. Roth VR, Theriault A, Clement C, Worthington J. Women physicians as healthcare leaders: a qualitative study.J Health Organ Manag. 2016 Jun 20;30(4):648-65. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-09-2014-0164.)

12. White D, Krueger P, Meaney C, Antao V, Kim F, Kwong JC. Identifying potential academic leaders: Predictors of willingness to undertake leadership roles in an academic department of family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2016 Feb;62(2):e102-9.

13. Angood P, Birk S. The value of physician leadership. Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun;40(3):6-20

14. U.S. News and World Report, July 16,2013, http://health.usnews.com/health-news/ best-hospitals/articies/2013/07/16/besthospitals-2013-14-overview-and-honor-roll.

15. Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: Is there an association? Social Science & Medicine, Elsevier, vol. 73(4), 535-539, August 2011.

16. Department of Health, Health Service Executive (11/4/14) Strategic review of medical training and career structure: report, Available at: http://www.lenus.ie/hse/bitstream/10147/317460/1/SRMTCSCareerStructuresReportFINAL.pdf (Accessed: 17/7/17).

(P733)