Paediatric Type 2 Diabetes Still Rare in an Irish Tertiary Referral Unit

R Kernan, A Carroll, N Mc Grath, CM Mc Donnell, NP Murphy

Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Children’s University Hospital, Temple St, Dublin 1.

Abstract

While Type 2 Diabetes in childhood has become increasingly prevalent throughout the world, in our service we found that only 2% (7/320) of children and adolescents with diabetes aged < 16 years had type 2 diabetes. All type 2 subjects were overweight or obese and six of seven were non-Caucasian. Mean age at presentation was 12.8 years. Six patients (85%) had complications, most commonly hypertension. Although Type 2 Diabetes in children remains relatively rare in our cohort, identification of these children is important as management differs from Type 1 Diabetes.

Introduction

Lifestyle changes and the epidemic of obesity have resulted in the emergence of insulin resistance and Type 2 Diabetes in children and adolescents. The incidence of Type 2 Diabetes is rising worldwide with an incidence rate of 0.22/1,000 10 -19 year olds in the US. 1,2. Approximately 25-45% of children and young adults diagnosed with diabetes in the US have Type 2 Diabetes while Australian data suggests a lower rate of 1-2% among their cohort3. Obesity, family history and non-Caucasian ethnicity are recognised risk factors for type 2 diabetes4. We aimed to identify all children and adolescents with Type 2 Diabetes attending our clinic and describe the prevalence, clinical characteristics and outcomes of Type 2 Diabetes in a tertiary paediatric diabetes service.

Methods

The Diabetes and Endocrinology service at Temple St is a tertiary referral service for >320 children with diabetes. Diagnostic criteria of American Diabetes Association are used for diagnosis of diabetes. We reviewed the clinical notes and laboratory results of all antibody negative children diagnosed with diabetes in our service between 2011 and 2015. The diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes was made in those patients with diabetes, negative autoantibodies and clinical signs of insulin resistance +/- persistence of C-peptide. Overweight and obesity was defined using WHO criteria of BMI z-score for age of +1-2SD as overweight and >2SD as obese5. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 95-99th centile for age / height. Blood pressure was measured at clinic visits; 24-hour BP recordings were not used.

Results

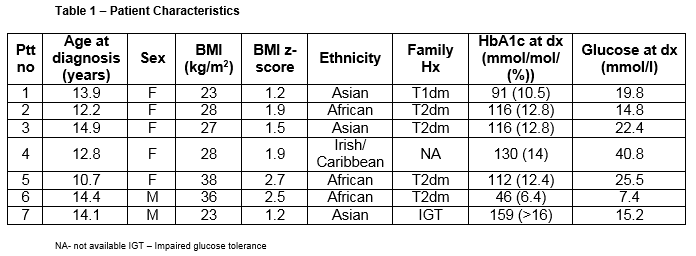

Patient characteristics

Seven of 320 patients (2.1%) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Patient characteristics are highlighted in Table 1. Mean age at presentation was 13.2 years. All patients were either overweight or obese with a mean BMI (range) z-score of 1.8 (1.2-2.7).

Diagnosis and management

The most common presenting symptoms were osmotic in 6 of 7 patients. One patient was identified through a screening OGTT after his sibling had presented. Three patients were ketotic at presentation, of which two were in DKA (mild and moderate). Five patients had acanthosis nigricans. All but one was initially managed with subcutaneous insulin. C-peptide level, suggestive of endogenous insulin production, was checked in 4/7 patients and was detectable in each case (Ptt no. 1,3,4&7).

Six patients were commenced on insulin at the time of diagnosis, with one patient treated initially with metformin alone. Metformin was added at follow up in all patients. All patients required ongoing insulin treatment. The average HbA1c at time of transition to adult services in this cohort was 70mmol/mol (8.6%).

Complications

Six of seven was hypertensive. Dyslipidaemia was seen in three patients and one patient had persistent microalbuminuria.

Discussion

In our study we found that Type 2 Diabetes accounted for only two percent of our cohort of patients with paediatric diabetes. These patients were all antibody negative, overweight or obese and non- Caucasian, apart from one patient from a mixed ethnic background. Most had a positive family history of Type 2 Diabetes and most were pubertal, a time of peak insulin resistance, at the time of diagnosis. These characteristics are often useful when trying to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes4. It is important to accurately diagnose Type 2 Diabetes in children and adolescents but it is not always straightforward. The presence of ketosis at diagnosis is not limited to Type 1 Diabetes , and has been described in up to 30% of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetics6. Three of our seven patients were ketotic at diagnosis. Measurement of c-peptide is useful as its persistence above the normal level for age would be unusual in Type 1 Diabetes 12-14 months post diagnosis7. C-peptide was detectable in all of our patients where it was measured. Diabetes autoantibody measurement is often useful when differentiating between type 1 and 2 diabetes; autoantibodies are usually negative in Type 2 Diabetes while they are positive in the vast majority (85-98%) of patients with type 1diabetes.

Metformin is the initial treatment of choice in metabolically stable type 2 diabetics but initial treatment is determined by symptoms, the severity of hyperglycaemia and ketosis/ketoacidosis7. Lifestyle modification, with emphasis on diet and exercise, is an essential component in management. Adolescents with Type 2 Diabetes are at particularly high risk of complications and may lose up to 15 years in life expectancy compared to adolescent peers without diabetes8. Complications occur at an earlier age than in adolescents with type 1 and are often present at the time of diagnosis9. Hypertension, dyslipidaemia and albuminuria were all seen in our cohort of patients.

Type 2 Diabetes remains relatively rare in our patients with diabetes. It is important to identify these patients as they are at particularly high risk for complications and also aspects of their management differ from those with Type 1 Diabetes . While optimal glycaemic control remains the aim in the management of both types of diabetes, lifestyle modification, oral agents and blood pressure control are key to optimal management of type 2 diabetes.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Corresponding Author

Dr Aoife Carroll, Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Children’s University Hospital, Temple St, Dublin 1.

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Grinstein G, Muzumdar R, Aponte L, Vuguin P, Saenger P, DiMartino-Nardi J. Presentation and 5-year follow-up of Type 2 Diabetes mellitus in African-American and Caribbean-Hispanic adolescents. Hormone research. 2003;60(3):121-126.

2. Group SfDiYS, Liese AD, D'Agostino RB, Jr., Hamman RF, Kligo PD, Lawrence JM, Liu LL, Loots B, Linder B, Marcovina S, Rodriguez B, Standiford D, Williams DE . The burden of diabetes mellitus among US youth: prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. Oct 2006;118(4):1510-1518.

3. Ruhayel SD, James RA, Ehtisham S, Cameron FJ, Werther GA, Sabin MA. An observational study of Type 2 Diabetes within a large Australian tertiary hospital pediatric diabetes service. Pediatric diabetes. Dec 2010;11(8):544-551.

4. Kao KT, Sabin MA. Type 2 Diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. Australian family physician. Jun 2016;45(6):401-406.

5. WHO. WHO BMI-for-age (5-19 years).

6. Type 2 Diabetes in children and adolescents. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes care. Mar 2000;23(3):38-389.

7. Zeitler P, Fu J, Tandon N, Nadeau K, Urakami T, Barrett T, Maahs D. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2014. Type 2 Diabetes in the child and adolescent. Pediatric diabetes. Sep 2014;15 Suppl 20:26-46.

8. Rhodes ET, Prosser LA, Hoerger TJ, Lieu T, Ludwig DS, Laffel LM. Estimated morbidity and mortality in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. Apr 2012;29(4):453-463.

9. Eppens MC, Craig ME, Cusumano J, Hing S, Chan AK, Howard NJ, Silink M, Donaghue KC. Prevalence of diabetes complications in adolescents with type 2 compared with Type 1 Diabetes . Diabetes care. Jun 2006;29(6):1300-1306.

P679