Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors in an Irish General Practice

L. O’Mahony1, E. Yelverton2

1. North East Training Scheme, ICGP

2. Bryanstown Medical Centre, Drogheda, Co. Louth

Abstract

Aim

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are amongst the most frequently prescribed medicines. Evidence to date shows these are being inappropriately overprescribed. Although highly effective, PPIs are increasingly recognized to be associated with many adverse health outcomes. The aims of this study are to assess the extent and quality of PPI prescribing in an urban general practice.

Method

Retrospective chart review and descriptive analysis of all prescriptions issued over one month was undertaken to determine the frequency and duration of PPI use, the likely indications and results of endoscopic findings.

Results

PPIs represented 20% of all prescriptions issued in June 2017, of which 80% were on long-term therapy. Esomeprazole use prevailed. Low dose therapy was least frequently prescribed (7%) compared with high dose therapy (93%). PPI use increased with age, and duration of therapy was prolonged for greater than one year in the majority of patients. Patients were commenced therapy without clear indication in 40% of cases. Findings of endoscopic evaluation in 58 (64%) patients suggest PPI therapy was inappropriately continued in the majority of cases (81%).

Conclusion

Chronic inappropriate overprescribing of PPIs remains a concern and contribute potentially to patient harm and wasteful financial resources. The ongoing need to optimise PPI prescribing remains paramount. Clinicians are encouraged to prescribe judiciously and in accordance with evidence-based guidelines.

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors have been a remarkable therapeutic advancement in the management of a wide variety of gastric conditions since their introduction in the 1980s1. They are currently one of the most frequently prescribed medicines, representing 7% of all GMS prescriptions in 2016. Expenditure for these drugs currently exceeds €40 million per annum2. They are highly effective therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, NSAID-induced gastropathy and are an integral component in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori.

Despite a number of safety concerns associated with the long-term use of these medications, inappropriate drug usage remains highly prevalent3. Adverse health effects of PPIs include an increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia4, Clostridium difficile infection5, vitamin B12 deficiency and hypomagnesemia6, acute interstitial nephritis7, chronic kidney disease8, drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus9, an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures10 and rebound acid hypersecretion following medication discontinuation11. Furthermore, recent research from an observational study of United States veterans followed over five years suggests an excess risk of death among PPI users compared to non-users and those using H2 blockers. This excess mortality risk is reported to increase in proportion with duration of PPI exposure12.

These safety concerns associated with the prolonged use of PPIs highlight the importance of optimising inappropriate overprescribing in order to reduce both patient and economic burdens associated with these medications.

The aims of this study were to assess the extent, duration and quality of PPI prescribing, the likely indications for initiation and to determine whether an upper endoscopy was undertaken and the results thereof.

Method

A descriptive analysis of all prescriptions issued to all patients in June 2017 was undertaken in Bryanstown Medical Centre, Drogheda, Co. Louth, an Irish urban general practice with a list of 4166 patients, of which 1394 are GMS patients. Prescriptions were examined to determine the frequency of PPI use and retrospectively reviewed to determine the overall duration of long-term PPI therapy. Patient charts were reviewed to identify the indications for initiation and results of endoscopic findings. Long-term PPI therapy was defined as three of more months of use. PPI prescribing in combination therapy with NSAID was excluded.

Results

Results

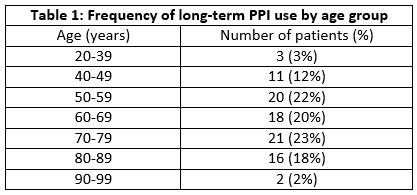

In June 2017, 2080 items were prescribed for 568 patients, of which 1281 (61%) items were repeat prescriptions. PPI use accounted for 20% of all drugs prescribed in June 2017. Esomeprazole (43%) and lansoprazole (33%) were most frequently used. Other less frequently prescribed PPIs included pantoprazole (12%), omeprazole (11%) and rabeprazole (1%). Eighty percent (80%) of all patients on PPI were on long-term therapy. Their mean age was 64 years (26-90years), 43 (47%) were male and 48 (53%) were female users. The frequency of long-term PPI use tend to increase with age, with the greatest number of users ranging from 50 to 79 years (Table 1). These patients were predominantly on full (58%) and double (35%) dose PPI compared with 7% on low dose therapy.

Full/double dose esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, omeprazole and rabeprazole are 20mg once daily/40mg once daily, 30mg once daily/30mg twice daily, 40mg once daily/40mg twice daily, 20mg once daily/40mg once daily and 20mg once daily/20mg twice daily, respectively. No low dose is available for esomeprazole, but for lansoprazole, pantoprazole, omeprazole and rabeprazole these are 15mg once daily, 20mg once daily, 10mg once daily and 10mg once daily, respectively13.

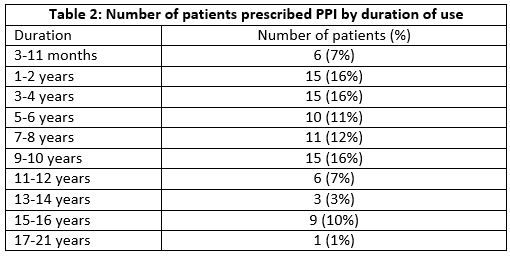

Duration of therapy was prolonged for greater than one year in the majority of cases (Table 2). Mean duration of long-term PPI therapy was seven years (three months-21years).

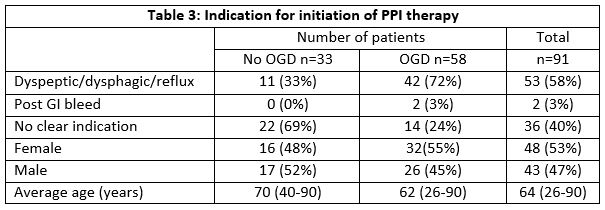

In the majority of cases, treatment was initiated for dyspeptic/dysphagic/reflux symptoms in 53 (58%) patients, post gastrointestinal bleed in two (2%) cases, while 36 (40%) patients were commenced therapy without clear indication having been recorded (Table 3).

Upper endoscopy was either not performed or not recorded in 33 (36%) cases. Among these patients, there was no difference between the proportion of men and women using PPIs (17 (52%) vs 16 (48%), respectively), and their mean age was 70 years (40-90 years). PPI treatment was commenced by for symptomatic control in 11 (33%) patients in this cohort and there was no clear indication recorded in the remainder 22 (67%) patients.

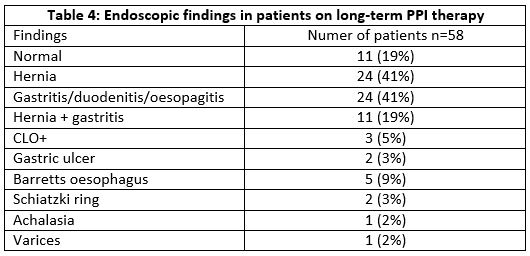

Of the 58 (64%) patients who underwent endoscopic investigation, mean age in this group was 62 years (26-90 years), with 26 (45%) males and 32 (55%) females undergoing endoscopy. The mean interval of time since their last endoscopy was three years (two months-11years). Among these patients, treatment was symptomatic in 42 (72%) patients, for gastrointestinal bleeding in two (3%), while in 14 (24%) no clear indication was recorded. Endoscopic findings are summarised in table 4.

Discussion

In this practice, PPIs represented 20% of all prescriptions issued over a one month period. Eighty percent of these prescriptions were for three or more months, which was considered in this study as being long-term therapy. Esomeprazole was most frequently prescribed (54%), despite lansoprazole currently deemed most cost effective14. PPI use increased with age, and duration of therapy was prolonged for greater than one year in the majority of cases. Full and double dose PPI were used most (93%) and low dose therapy least (7%), although no low dose is available for esomeprazole13. PPI therapy was initiated in 40% of cases without clear clinical indication recorded. In patients who underwent endoscopic evaluation, long-term therapy was considered appropriate in 11 (19%) patients; in those who had Barrett’s oesophagus, gastric ulcer, Schiatzki ring, achalasia and varices found on endoscopy. Long-term PPI therapy was considered inappropriate in 11 (19%) patients who had normal endoscopic findings and also in the remainder 36 (62%) patients who were found to have a positive rapid urease (CLO) test, a hernia and gastritis/duodenitis/gastritis on endoscopic findings. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy are possible reasons for justifying this high prevalence of long-term PPI prescribing.

Overprescribing of PPIs is a concern both in primary and secondary care. Since their introduction in the 1980s, Irish pharmacy claims data from the Eastern Health Board region of Ireland revealed that PPI use has increased from 0.8% to 24% between 1997 and 201215. Similarly, an analysis of the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) in the UK found PPI use had increased from 0.2% to 15% between 1990 and 201416. Substantial increases in prescribing have also been reported in Denmark17 and Australia18.

Inappropriate prescribing practices appear to contribute to the prevalence of PPI prescribing. In a one-week study of non-elective admissions to an Irish hospital, PPI therapy accounted for 35% of pre-admission medications. Of these there was no clear indication documented in 92% of cases, although following patient interview a justification for ongoing treatment was identified in 35%19. A study of acid suppressive therapy in hospital inpatients in the United States found that 29% of patients were using therapy prior to admission. This increased to 71% during admission, for whom only 10% were deemed to have an acceptable indication. PPIs prescribed at discharge increased to 54%20. Continuation of PPI therapy in the majority of cases at 6 months after discharge was found in studies in Wales21 and New Zealand22. In Denmark, long-term therapy was identified in 34% at 6 months follow up of prescriptions issued by general practitioners23. In this study, long-term prescribing of PPIs in this urban Irish general practice appears also to be prevalent.

Chronic overprescribing of PPIs remains an ongoing challenge. To date studies have shown that educational interventions or reimbursement modifications to encourage optimal PPI use have failed to have an effect on the frequency or appropriateness of treatment21,17. This may likely reflect a failure of clinicians to re-evaluate the need for continuation of treatment, or to insufficient use of step-down or on-demand therapy24. The UK GPRD study found that deprescribing of PPIs was not attempted in 60% of long-term PPI users16. Failure of deprescribing may be also likely attributed to cases of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease despite PPI treatment. Observational primary care and community studies reported 45% of such cases25. Patient may also be reluctant to stop therapy, likely due to symptoms associated with acid rebound hypersecretion following discontinuation11.

PPIs are effective and widely available for a variety gastric conditions. However, ongoing inappropriate chronic use may potentially contribute to patient harm and unnecessary financial waste. Although challenging, there is an ongoing need to optimise PPI prescribing. Clinicians are encouraged to prescribe judiciously, to routinely re-evaluate their repeat prescribing practices and to deprescribe where clinically appropriate and when benefits overweigh potential harms.

This study raises awareness of overprescribing of proton pump inhibitors in an Irish general practice. However, being a single-practice study, generalisability cannot be assumed. Our results are limited also by the short study interval so that prescribing patterns over time were not captured. The prevalence of PPI-associated morbidity, potential drug interactions and an economic analysis might also warrant further study in an Irish setting.

Acknowledgement

Niall Maguire, GP and Associate Director of GP training, North East Training Scheme, ICGP.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest declared.

Corresponding Author

Laura O’Mahony,

GP Registrar,

North East Training Scheme,

ICGP

Email: [email protected]

References

1. McDonagh MS, Carson S, Thakurta S. Drug Class Review: Proton pump inhibitors: Final report update 5 (internet). Portland (OR): Oregan Health and Science University, 2009 May

2. Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS) statistical analysis of claims and payments 2016. https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/pcrs/pcrs-publications/pcrs-annual-report-20161.pdf

3. Marks DJB. Time to halt the overprescribing of proton pump inhibitors. Clinical Pharmacist 2016 Aug;8(8).

4. Zirk-Sadowski J, Masoli JA, Delgado J, Hamilton W, Strain WD, Henly W, Melzer D, Ble A. Proton pump inhibitors and long-term risk of community-acquired pneumonia in older adults. J Am Geriatric Society 2018 Apr 20. doi:10.1111/jps.15385

5. Trifan A, Stanciu C, Girleanu I, Stoica OC, Singeap AM, Maxim R, Chiriac SA, Ciobica A, Boiculese L. Proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterology 2017 Sept 21;23(35):6500-6515. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i35.6500

6. Heidelbaugh JJ. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety 2013 Jun;4(3):125-133. doi: 10.1177/2042098613482484.

7. Sampathkumar K, Ramalingam R, Prabakar R, Abraham A. Acute interstitial nephritis due to proton pump inhibitors. Indian J Nephrology 2013 Jul-Aug;23(4):304-307.

8. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, Sang Y, Chang AR, Coresh J, Grams ME. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med 2016 Feb 1;176(2):238-246. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193.

9. Sandholdt LH, Laurinaviciene R, Bygum A. Proton pump inhibitor-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatology 2014 Feb;170(2):342-51. doi: 10.111/bjd.12699.

10. Zhou B, Huang Y, Li H, Sun W, Liu J. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: an update meta-analysis. Osteoporosis Int 2016 Jan;27(1):339-47

11. Rochoy M, Dubois S, Glantenet R, Gautier S, Lamber M. Gastric acid rebound after a proton pump inhibitor: Narrative review of literature. Therapie 2018 May-June, 73(3):2377-246. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2017.08.005.Epub2017 Oct26.

12. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, Xian H, Yen Y, Al-Aly Z. Risk of death among users of proton pump inhibitors: a longitudinal observational cohort study of United States veterans. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015735. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015735

13. Appendix A: Dosage information on proton pump inhibitors. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management CG184 2014

14. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/medicines-management/preferred-drugs/

15. Moriarty F, Bennett K, Cahir C, Fahey T. Characterizing potentially inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older people in primary care in Ireland from 1997 to 2012. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2016 Dec;64(12):e291-e296. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14528. Epub 2016 Nov 7.

16. Othman F, Card TR, Crooks CJ. Proton pump inhibitor prescribing patterns in the UK: a primary care database study. Pharmacoepdemiology and Drug Safety 2016 Sep;25(9):1079-87. doi: 10.1002/pds.4043. Epub 2016 Jan 3.

17. Haastrup P, Paulsen MS, Zwisler JE, Begtrup LM, Hansen JM, Rasmussen S, Jarbøl DE. Rapidly increasing prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care despite interventions: A nationwide observational study. European Journal of General Practice 2014 Dec;20(4):290-3. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2014.905535. Epub 2014 Apr 29.

18. Hollingworth S, Duncan EL, Martin JH. Marked increase in proton pump inhibitors use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiology Drug Safety 2010 Oct;19(10):1019-24. Doi: 10.1002/pds.1969.

19. Moran N, Jones E, O’Toole A, Murray F. Appropriateness of a proto pump inhibitor (prescription. Irish Med J 2014 Nov-Dec;107(10);329-7.

20. Pham CQ, Regal RE, Bostwick TR, Knauf KS. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother 2006 Jul-Aug;40(7-8):1261-6. Epub 2006 Jan 27..

21. Batuwitage BT, Kingham JGC, Morgan NE, Bartlett RL. Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2007 Jan;83(975):66-68. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.051151.

22. Grant K, Al-Adhami N, Tordoff J, Livesey J, Barbezat G, Reith D. Continuation of proton pump inhibitors from hospital to community. Pharmacy World and Science 2006 Aug;28(4):189-93. Epub 2006 Oct 26.

23. Haastrup PF, Rasmussen S, Hansen JM, Christensen RD, Sondergaard J, Jarbøl DE. General practice variation when initiating long-term prescribing of proton pump inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Family Practice 2016 17:57. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0460-9.

24. Heidelbaugh JJ, Kim AH, Chang R, Walker PC. Overutilization of proton pump inhibitors: what the clinician needs to know. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology 2012 Jul;5(4):219-32. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12437358.

25. El-Serag H, Becher A, Jones R. Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2010 Sept;32(6):720-37. doi 10.1111/j.1365-2036.04406.x.

P932