Prevalence of Smoking and Provision of Smoking Cessation Advice during Hospitalization

N. Najeeb 1, M. Halawani 1, N.G. McElvaney 2,3, F. Doyle 4

1.Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 123 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland.

2.Respiratory Research division, Department of Medicine, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 123 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland.

3.Education and Research Centre, Beaumont Hospital, Beaumont, Dublin 9, Ireland.

4.Department of Psychology, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 123 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland.

Abstract

Aim

We aimed to determine the prevalence of smoking and smoking cessation advice received by inpatients in Beaumont Hospital and compared results to previous similar studies.

Method

Cross-sectional survey where we interviewed eligible in-patients over a two-week period.

Results

14.8% (30/203) of participants were current smokers, which is lower than the smoking prevalence found by previous studies. The rate of cessation advice delivery was 53.3% (16/30). An increasing socioeconomic gap between smokers and non-smokers over time was found.

Discussion

There remains limited provision of smoking cessation advice to inpatients.

Introduction

Smoking is a risk factor for a wide range of diseases, most commonly cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and cancers.1 the provision by healthcare professionals of brief smoking cessation advice opportunistically to smokers is known to increase quit attempts and rates.2,3,4,5 In Ireland, only a third of smokers who happened to be in contact with healthcare professionals in the previous year had received advice encouraging them to quit, according to Healthy Ireland Survey 2016.6 Similar results have been published for inpatient settings, where between 38%-56% of inpatients reported receiving cessation advice around their time of hospitalisation.7,8,9 We aimed to determine whether the prevalence of the provision of such cessation advice had changed since these studies. We also explored attitudes to cessation and sociodemographic characteristics of smokers.

Method

This cross-sectional study was conducted by interviewing in-patients attending Beaumont hospital, replicating the methodology of previous studies.7,8,9 Participants completed 5-15 minutes interview, which took place from 22nd February to 9th March 2017. The recruitment was conducted by two medical students who worked on interviewing the patients from 9am-5pm, five days a week. Patients were excluded from participation if they refused, were under 18 years of age, considered too unwell by clinical staff, cognitively impaired, unable to complete the interview due to fragility, unable to speak English or if deaf. All Beaumont hospital wards were covered apart from the following wards: the renal transplant ward was excluded because medical students, the interviewers, were not allowed in the renal transplant ward. The renal ward was excluded as it had an infectious outbreak at the time of the survey. The Intensive care unit and emergency department were excluded. Finally, the paediatric ward was also excluded by definition. All patients in the rest of the wards were invited to participate unless they met one of the exclusion criteria above or if they refused. Neither St. Joseph’s Hospital in Raheny, which is under the management of Beaumont Hospital Board, nor the Ashlin Centre for psychiatric in-patients was included in this survey.

We obtained ethical approval from Beaumont Hospital Ethics (Medical Research) Committee. After finding the eligible patients, the recruiters would explain to them the purpose of the research, give them the patient information leaflet, and obtain signed consent. The recruiters would then go through each of the questions of the survey with each participant by a face-to-face interview. At the end of the interview, recruiters would advise interested current smokers to tell their hospital doctors to refer them to Beaumont Hospital Tobacco Cessation Support Service, and to ask for nicotine replacement patches to help them quit.

We defined current smokers as those still smoking at the time of the survey. Ex-smokers are those who had quit smoking. Never-smokers are those who had not smoked a minimum of 100 cigarettes in their entire life. While current non-smokers were those not currently smoking including never-smokers and ex-smokers. The questions related to smoking were only answered by current smokers. Nicotine dependence level was deduced by using the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence.10 The Motivation to Stop Scale (MTSS) was used to assess readiness to quit.11 The population were divided into categories according to their diagnoses, using the international classification of diseases, ICD-10, 2016 after merging some of its classes.12 Group differences were assessed using X2, Mann-Whitney U and t-tests as appropriate.

Results

Response rate and smoking prevalence

From a potential number of 641 in-patients in Beaumont, only 203 patients participated in the study. Failure to participate for the massive majority was due to ineligibility rather than refusal. The percentages of current smokers, ex-smokers and never smokers were 14.8% (30/203), 46.3% (94/203) and 38.9% (79/203) respectively. Among these, there were two patients (0.01%) who were currently using e-cigarettes only.

Sample profile and nicotine dependence

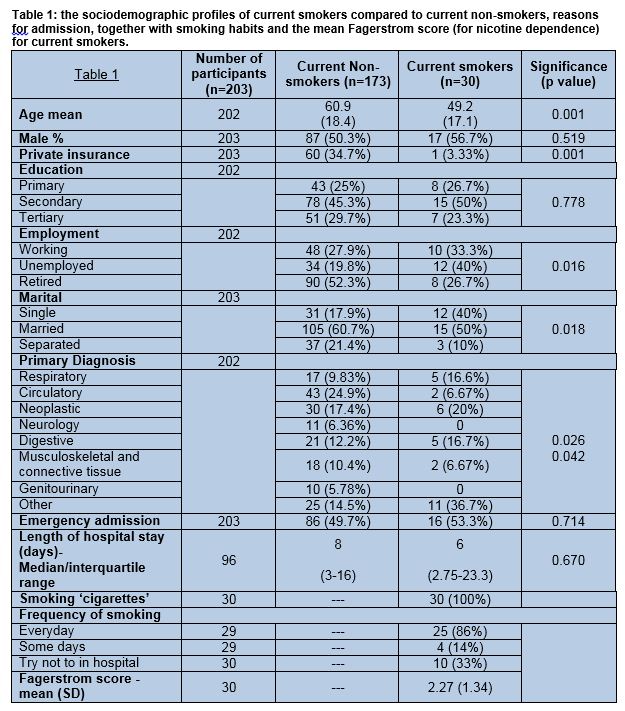

According to Table 1, current smokers were younger, less likely to have a private insurance, and less likely to be retired. Smokers were also more likely to be single and less likely to be married/separated/widowed than non-smokers. No other group differences were found. Mean for Fagerström score for smokers was 2.26 (SD = 1.33), indicating a very low nicotine dependence level overall.

Changes in smoking prevalence and smokers’ sociodemographics over time

Our study showed a smoking prevalence of 14.8% (30/203) among Beaumont hospital in-patients. This is markedly lower than the Beaumont smoking prevalence found by two previous studies with comparable data (21% in 2011, and 17% in 2013).7,9

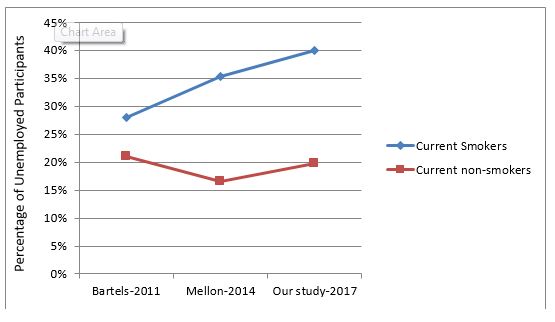

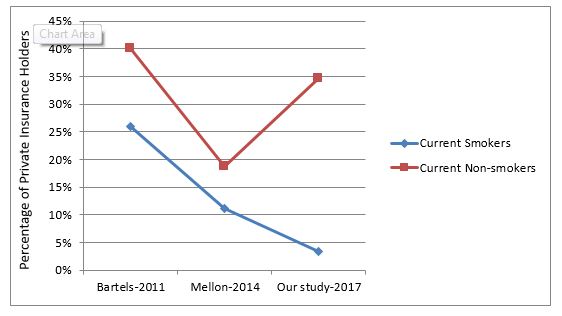

Social disparities between current smokers and current non-smokers, predicted by their employment status and the type of insurance they hold, were shown to be larger than in two previous studies as shown in Figures 1 and 2 below.7,8

Figure 1: smoking and unemployment over time. The proportion of current smokers who are ‘unemployed compared to the proportion of non-smokers who are unemployed in three different studies. The percentage of unemployed current smokers is noticed to be increasing, while the percentage of unemployed non-smokers is largely constant.

Figure 2: smoking and holding a private insurance over time. The proportion of current smokers who are private insurance holders compared to the proportion of non-smokers who are private insurance holders in three different studies. The percentage of current smokers who hold a private insurance, which was always less than that for non-smokers, seems to be continuously decreasing.

Figure 1 shows that the percentages of current smokers who are unemployed are much higher than the percentages of non-smokers who are unemployed in all three studies. This is partly due to current smokers belonging to the younger working age group, as evident in Table 1. However, it is also noticed that the rate of unemployment among current smokers in particular has increased over the past several years. Figure 2 shows that the percentage of current smokers holding a private insurance, which was always less than that for non-smokers, is continuously decreasing.

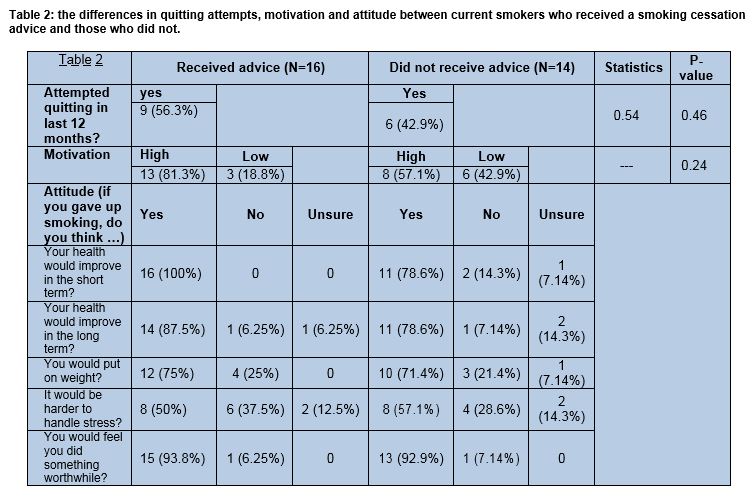

Advice delivery; its prevalence, significance and comparison with previous studies

The prevalence of current smokers who reported receiving smoking cessation advice in the last 12 months in this study was 53.3% (16/30), while the prevalence of those who reported their wish to receive such advice while in hospital was 50% (15/30). When compared to two previous studies, advice delivery rate in Beaumont is found to be increasing over time, from 44% in 2011, to 50% in 2013, and to 53.3% in 2017 (our study).7,9 From Table 2, 56.3% (9/16) of current smokers who received advice reported having tried to quit, compared to 42.9% (6/14) of those who did not receive the advice. Patients who received quitting advice were overall more motivated towards smoking cessation than the other group, albeit these differences were not significant due to the small number of smokers.

Attitude to smoking cessation

The majority of current smokers, whether received advice or not, showed positive attitudes towards quitting in terms of their positive perception of the effect of cessation on short-term and long-term health and by considering smoking cessation to be something worthwhile doing. Most patients, however, found that maintaining their weight and handling stress would be obstacles against them quitting. This can be seen in Table 2.

Discussion

Our study found a smoking prevalence of 14.8%, which is lower than the smoking prevalence in Beaumont found by two previous studies (21% in 2011, and 17% in 2013).7,9 The advice delivery rate found by our study was 53.3%, which is higher than the rates found by the previous studies (44% in 2011 and 50% in 2013).7,9 This shows that more patients are quitting and that advice delivery service is slowly improving.

An increasing socioeconomic gap between smokers and non-smokers was also found in our study. This is important to consider as it may affect the physicians’ attitude to deliver advice. Several American studies showed that American physicians are more likely to deliver cessation advice to higher socioeconomic class patients.13,14 Future studies should investigate whether or not this is true in Ireland. Lower socioeconomic groups are those whose health is worse and quality of life lower generally, making them less attentive to their health. In order for these people to fully benefit from healthcare services, broader changes are continuously required; changes on the governmental level focusing on improving the quality of life for these groups.15,16 Nevertheless, As reported by one study done on smokers living in very disadvantaged areas in the UK, these groups were in deep need of a non-judgemental attitude from healthcare providers and would benefit from reassurance about the low-cost and effectiveness of the available alternatives to cigarettes.17 This draws attention to the importance of advice delivery especially to these groups.

The study had several limitations. First of all, the results were based on patients’ reporting and thus exposed to bias. Secondly, less than half of Beaumont hospital in-patients participated in the study meaning the sample cannot be considered representative of the hospital population, especially that the characteristics of those ineligible or refusing to participate were not recorded. Thirdly, the sample size of smokers was small, and a large, (inpatient) population-weighted study would be required to estimate the true prevalence of smoking and cessation care. Fourthly, the medical charts of patients were not accessed, and it may be that cessation counselling was indeed recorded in charts, although previous research would suggest that this is unlikely.8 Fifthly, the study was cross-sectional, not allowing us to see the long-term effect of recent advice delivery. Finally, it would have been more informative if recent ex-smokers were asked whether they received cessation advice within the last year and prior to quitting.

In conclusion, the study showed a decreasing smoking prevalence among hospitalised patients in Beaumont recently, an increasing socioeconomic gap between smokers and non-smokers, an increasing rate of advice delivery over the past few years, and a non-significant but positive effect of smoking cessation advice delivery on quitting attempts as well as motivation to smoking cessation. Since there is still a large room for improvement, healthcare professionals and policy makers should look for new ways to improve cessation services. One mechanism that could be further investigated is allowing healthcare professional students to deliver cessation advice during their training.18

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Correspondence:

Noor Najeeb, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 123 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland.

Email Address: noornajeeb@rcsi.com

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Health effects of cigarette smoking. [Updated: December 1, 2016; cited April 1, 2017] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/

2. Rigotti NA, Clair C, Munafò MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients: an update. Cochrane Database of systemic reviews. 2012;(16): CD001837

3. Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews. 2013;(5): CD000165

4. Bao Y, Duan N and Fox S. Is Some Provider Advice on Smoking Cessation Better Than No Advice? An Instrumental Variable Analysis of the 2001 National Health Interview Survey. Health Services Research. 2006;41(6), 2114-2135.

5. Lancaster T and Stead L F. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017;(3): CD001292

6. Ipsos MRBI. Healthy Ireland Survey 2016. Department of health Ireland. 2016

7. Bartels C A A, McGee H, Morgan K, McElvaney N G, & Doyle F. A survey of the prevalence of smoking and smoking cessation advice received by inpatients in a large teaching hospital in Ireland. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2012;181(3), 445–449.

8. Mellon L, McElvaney N, Cormican L, Hickey A, Conroy R, Ekpotu L, Oghenejobo O, Atteih S, McDonnell R and Doyle F. Determining rates of smoking cessation advice delivered during hospitalisation and smoking cessation rates 3 months post discharge: a two-hospital survey. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine. 2016;4(1):124-137.

9. Ohakim A, Mellon L, Jafar B, O’Byrne C, McElvaney NG, Cormican L, McDonnelle R and Doyle F. Smoking, attitudes to smoking and provision of smoking cessation advice in two teaching hospitals in Ireland: Do smoke-free policies matter? Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine. 2014;3(1): 142–153.

10. Fagerstrom K, Russ C, Yu C, Yunis C, Foulds J. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence as a Predictor of Smoking Abstinence: A Pooled Analysis of Varenicline Clinical Trial Data. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(12):1467-1473.

11. Kotz D, Brown J and West R. Predictive validity of the Motivation To Stop Scale (MTSS): A single-item measure of motivation to stop smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013; 128(12): 15–9.

12. World Health Organisation [Internet]. International Classification of Diseases. [Updated: November 29, 2016; cited April 2, 2017] Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/

13. Cipher D J, Hooker R S, Sekscenski E. Are older patients satisfied with physician assistants and nurse practitioners? Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2006 Jan 1;19(1):36-44.

14. Houston T, Scarinci I, Person S, Greene P. Patient Smoking Cessation Advice by Health Care Providers: The Role of Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(6):1056-1061.

15. Jarvis M J, Wardle J. Social patterning of individual health behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R, eds. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press Inc; 1999:240–255.

16. Lawlor D, Frankel S, Shaw M, Ebrahim S, Smith G. Smoking and Ill Health: Does Lay Epidemiology Explain the Failure of Smoking Cessation Programs Among Deprived Populations?. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):266-270.

17. Roddy E, Antoniak M, Britton J, Molyneux A, Lewis S. Barriers and motivators to gaining access to smoking cessation services amongst deprived smokers–a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2006 Nov 6;6(1):147.

18. Kumar A, Ward KD, Mellon L, Gunning M, Stynes S, Hickey A, Conroy R, MacSweeney S, Horan D, Graduate Entry Programme 2014-18 Class, Cormican L, Sreenan S and Doyle F. Medical student INtervention to promote effective nicotine dependence and tobacco HEalthcare (MIND-THE-GAP): single-centre feasibility randomised trial results. BMC Medical Education. 2017;17(1).

P821