Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Prostate Presenting in a 44 Year Old

M. Conroy1, M. Greally1 , O. MacEneaney2, C. O’Keane2, J. McCaffrey1

1.Department of Medical Oncology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin

2.Department of Pathology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin

Abstract

We present the case of a 44-year-old man diagnosed with metastatic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate. The pathogenesis and optimal treatment of this rare and aggressive subtype of prostate cancer are not fully clear. The patient was managed using a multimodality approach of chemotherapy, hormonal blockade and radiation therapy, with palliative intent.

Introduction

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (also known as carcinosarcoma) of the prostate is a rare subtype of prostate cancer with a propensity for early local invasion and distant metastasis. While often occurring on a background of prostate adenocarcinoma, it may also arise de novo. We describe a case in a man who initially presented with haematuria.

Case report

A 44-year-old male was referred to the urology service with a short history of haematospermia, and haematuria. He had no past medical history of note. Digital rectal examination revealed a large prostate with a nodule in the right gland base. Serum PSA was in the normal range. While awaiting urgent imaging and biopsy he required hospital admission for urinary retention and severe pain.

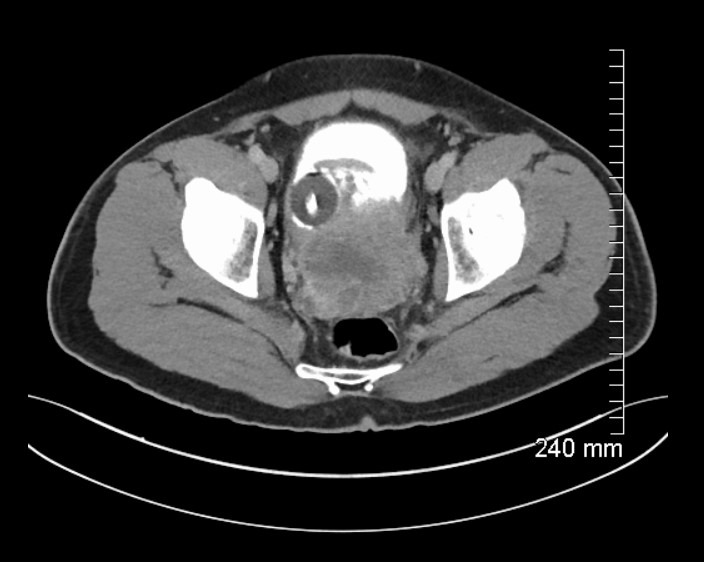

MRI prostate showed an 11cm, ill-defined, heterogeneous mass in the pelvis, arising from the left side of the prostate (Figure 1), invading the bladder and abutting the sigmoid colon. CT urogram showed central necrosis of the mass and CT thorax demonstrated bilateral pulmonary nodules suggestive of metastatic disease. Radionucleotide bone scan showed no bone metastases.

Figure 1: MRI prostate demonstrating mass arising from left side of prostate

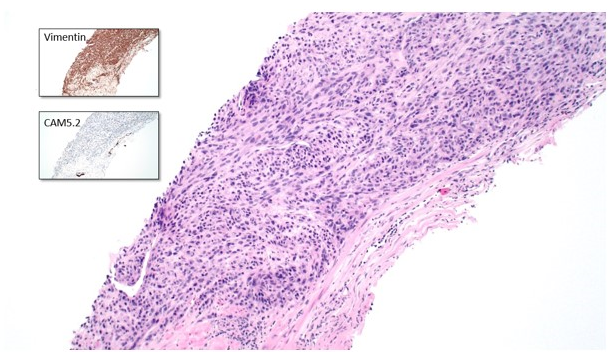

A prostate biopsy demonstrated a carcinoma consisting of hyperchromatic spindle and epithelioid cells arranged in a fascicular pattern, with occasional bizarre nuclei and giant cells (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed an unusual pattern of dot-like cytokeratin expression, diffusely positive vimentin and focal racemase positivity. IHC for neuroendocrine markers and PSA was negative. The findings were considered most consistent with a sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate.

Figure 2: 100x magnification of prostate lesion with inserts demonstrating IHC findings.

The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting. The patient commenced androgen blockade and a course of pelvic radiotherapy for symptom control. The radiotherapy was effective at reducing pain, and his urinary catheter was removed, but it did not resolve the haematuria. Unfortunately, he presented again four months later with dyspnoea and chest pain. Imaging showed disease progression with a left pleural effusion and a cardiac metastasis in his right ventricle. The patient underwent a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) talc pleurodesis to relieve his symptoms. A biopsy of the pleural lesion taken at this time confirmed sarcomatoid prostate cancer. As he still had a good performance status, he was at this point commenced on palliative chemotherapy with docetaxel, at a dose of 50mg/m2 every two weeks. This was chosen empirically based on its indication in the management of prostate adenocarcinoma, and reported use in case series of patients with sarcomatoid prostate cancer1,2. However, his performance status declined shortly afterward, and further active treatment was discontinued in favour of palliative care.

Discussion

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (also described as ‘carcinosarcoma’) of the prostate, represents less than 0.1% of all prostatic malignancies.

Morphologically, sarcomatoid carcinoma has a malignant epithelial component and a distinct population of sarcomatoid or mesenchymal-appearing cells. The adenocarcinoma is typically high grade (76%), or an unusual form of prostate carcinoma (ductal, small cell or squamous cell) (21%). The sarcomatoid component is most commonly an undifferentiated spindled form; heterologous components may be present that resemble osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma or rhabdomyosarcoma. Atypia is present in 55% of cases, in the form of bizarre nuclei and giant cells1.

With regard to pathogenesis, the epithelial and sarcomatoid components likely arise from a single cell of origin, rather than separate tumour types. A case series1 showed that 66% of patients had a previous diagnosis of acinar adenocarcinoma, favouring an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. That hypothesis is strengthened by the identification of a prostate-specific gene deletion in both the sarcomatoid component and the adjacent adenocarcinoma3. Increased p53 expression has been suggested as a potential molecular alteration in these lesions4. Prior radiation and hormonal blockade have been suggested to predispose to sarcomatoid carcinomas5, 6, 7 but without clear evidence, and these may simply be confounders.

Clinically, this tumour behaves aggressively, with a propensity for local invasion and early visceral metastasis. Bladder invasion and metastatic disease are correlated with poor prognosis, associated with a median overall survival of 9 months and 7.1 months, respectively2. PSA is frequently normal and is not a reliable guide to response or progression8. Best outcomes seem to be achieved in localised disease managed with radical resection and radiation. Locally advanced or metastatic disease may be managed with hormonal blockade, chemotherapy or radiation, but responses are short-lived7. Greater understanding of the tumour biology and molecular profiling may provide a basis for different therapeutic strategies in this rare malignancy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Correspondence:

Dr. Michael Conroy,

Department of Medical Oncology,

Mater Misericordiae University Hospital,

Eccles Street,

Dublin 7

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Hansel DE, Epstein JI. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate: a study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006 Oct;30(10):1316-21.

2. Markowski MC, Eisenberger MA, Zahurak M, Epstein JI, Paller CJ. Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Prostate: Retrospective Review of a Case Series From the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Urology. 2015 Sep;86(3):539-43. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.06.011

3. Rodrigues DN, Hazell S, Miranda S, Crespo M, Fisher C, de Bono JS, Attard G. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate: ERG fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirms epithelial origin. Histopathology. 2015 May;66(6):898-901. doi: 10.1111/his.12493

4. Delahunt B, Eble JN, Nacey JN, Grebe SK. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate: progression from adenocarcinoma is associated with p53 over-expression. Anticancer Res. 1999 Sep-Oct;19(5B):4279-83.

5. Canfield SE1, Gans TH, Unger P, Hall SJ. Postradiation prostatic sarcoma: de novo carcinogenesis or dedifferentiation of prostatic adenocarcinoma? Tech Urol. 2001 Dec;7(4):294-5.

6. Domínguez A, Piulats JM, Suárez JF, Condom E, Castells M, Camps N, García Del Muro FX, Franco E. Prostatic sarcoma after conservative treatment with brachytherapy for low-risk prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2013 Aug;52(6):1215-6. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.734927.

7. Perez N, Castillo M, Santos Y, Truan D, Gutierrez R, Franco A, Palacin A, Bombi JA, Campo E, Fernandez PL. Carcinosarcoma of the prostate: two cases with distinctive morphologic and immunohistochemical findings. Virchows Arch. 2005 May;446(5):511-6.

8. Leibovici D, Spiess PE, Agarwal PK, Tu SM, Pettaway CA, Hitzhusen K, Millikan RE, Pisters LL. Prostate cancer progression in the presence of undetectable or low serum prostate-specific antigen level. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):198-204.

P825