Smoking Behaviour among People Living with HIV and AIDS: A Sub-Group Comparison

K Babineau, S O Dea, G Courtney, L Clancy

TobaccoFree Research Institute Ireland, DIT Kevin St, Focas Research Building, Camden Row, Dublin 8

Abstract

Recent advancements in the treatment of HIV have significantly improved long-term health outcomes and life expectancy among people living with HIV/AIDS. As such, healthcare professionals have begun to focus more seriously on health protective behaviour changes that could further reduce mortality including smoking and tobacco dependence. A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 438 people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) attending a clinic in an urban area to measure current smoking behaviours. After removing missing data, the final sample was 402 service users. Among those surveyed 141 (35.0%) were current smokers with 35 (8.2%) ex-smokers. Rates among key sub-groups were higher. Comparatively, smoking prevalence was very low among African migrants (8, 7.2%), particularly African born women (1, 1.3%). In line with international studies, smoking prevalence among PLWHA was nearly double that of the general population. These findings come at a time when smoking in the general population in Ireland is at an all-time low, making the need to address tobacco dependence among PLWHA all the more vital.

Introduction

The epidemiology of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is complex and dynamic, as disease rates among subgroups have transformed and migrated over the past three decades1,2. While HIV/AIDS has caused alarming mortality among injecting drug users and men who have sex with men (MSM), the transmission among people in Sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for more than two/thirds of HIV infections world-wide, has proved to be the most devastating to date3,4. Today, the epidemic is widely understood to be in decline, yet there are several identified key sub-populations within which transmissions remain persistent including injecting drug users (IDUs) in Europe and Central Asia, young women and girls in southern Sub-Saharan Africa, and young MSM in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa1.

Recent medical advancements in the treament of HIV, including highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), have significantly improved long-term health outcomes and life expectancy5,6. As such, many healthcare professionals have begun to focus more seriously on health protective behaviour changes that could further reduce mortality and co-morbidity among PLWHA7. One of the most prominent and preventable behavioural health risks among many PLWHA is smoking and tobacco dependence8,9. Smoking prevalence among the general population in Ireland and the US is currently less than 20%10, 11. However, studies conducted among PLWHA in the US have reported rates ranging from 40.5% to 50%, putting their prevalence at two to three times that of the general population12-16. As is well established, smoking remains the leading cause of preventable disease including lung cancer and cardiovascular disease among the general population17. It is also a major risk factor for peripheral vascular and coronary artery disease, increasing the risk for cardiovascular disease complications and stroke. Furthermore, smoking increases the risk for many types of cancer including cancer of the stomach, pancreas, cervix, kidney, and oral cavity18. In addition to the many well-documented risks, smoking has been linked with many HIV-specific health problems. Current smokers are at a greater risk than non-smokers for major cardiovascular disease, COPD, non-AIDS cancer, and all-cause mortality12. Smoking in the HIV population also has a negative impact on quality of life and survival. Among a sample of 585 HIV-infected persons in the United States, smoking was significantly associated with decreasing scores in all dimensions of health-related quality of life19. Furthermore, it’s been demonstrated that cigarette smoking itself is an independent predictor of non-adherence to HAART, while ex-smokers did not differ from never smokers in adherence rates20. This observation suggests that smoking cessation serves as a strategy for better anti-retroviral adherence while also promoting overall improved health in the HIV population.

While some studies have focused on smoking behaviours among particular sub-groups of PLWHA (e.g. MSM, pregnant women), there are few that have compared smoking behaviours directly among a cohort of PLWHA attending a treatment centre in one locality15, 21. Furthermore, there is no documented scholarly evidence identifying the present demographic subgroups of PLWHA within Ireland. This study aimed to gather data on key demographics of HIV service users, along with information on smoking behaviour and readiness to quit to further understand the needs of PLWHA in Ireland and the nature of smoking behaviour among main subgroups.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in a public HIV treatment clinic in an urban area in Ireland from July-October 2014. The ‘HEAL’ clinic (pseudonym) provides on-going, anti-retroviral treatment to people living with HIV and AIDS, free of charge. At present, the HEAL clinic does not have a formal smoking cessation programme embedded in its services. Prior to data collection, ethical approval for the study was gained from the Tallaght Hospital/St. James Hospital Joint Research Ethics Committee. Two hand-held digital devices were used in the administration of the survey. The survey was constructed and imported into a survey-delivery app known as ‘Quicktap’ which allows participants to complete questionnaires on hand-held digital tablets. In this format, each question appeared on the screen with the pre-designated response categories or write-in format. After responding to a question, the next question appeared on the screen. Researchers collaborated with the medical staff of the HEAL clinic, who kindly agreed to assist with the data collection. One researcher and one research nurse were in charge of survey administration. During daily clinical hours, service users arrived at the clinic and waited in a common area prior to their previously scheduled appointments. Research staff then individually asked all service users present if they would be willing to fill out a survey on smoking behaviour. Participants were informed, verbally, that the survey was 100% voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. They were told that they could skip any questions that they did not want to answer and were reassured that if they chose not to participate, their treatment at the clinic would in no way be affected. Prior to administering the survey, participants gave informed consent by reading a short introduction on the screen and clicking ‘I understand’ to the statements therein. In the event that the participant needed help operating the device, assistance was offered. The survey took approximately 10-15 minutes to complete.

Demographic variables collected included age, ethnicity, country of birth, education level, and sexual orientation along with items relating to injecting drug behaviour, methadone maintenance therapy, and sexual partners. Several items related to past and current smoking behaviour, second hand smoke exposure, and willingness to quit were also included. These items were selected from a series of items recommended by the World Health Organization and the Centre for Disease Control and Preventation22, 23. A binary variable for smoking status was created where participants who have a history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and are currently smoking at least one cigarette a week were classified as ‘current smokers’. This definition of was ‘current smoking’ was decided upon in order to compare with national data produced by Ireland’s National Health Service11. Participants also completed the brief SF-8 health survey, a widely used, health-related quality of life instrument24. The SF-8 contains eight 6 point scale items relating to self-reported physical and mental well-being over the past four weeks (e.g. In the past four weeks, how often did your personal or emotional problems keep you from doing your usual work?). All responses were imported into SPSS version 21 for analysis. Descriptive statistics (means, medians, frequencies) were generated for all variables. A total of 507 service users were approached and asked to complete the survey. Over the three-month study, 41 opted not to participate and an additional 28 had large amounts of missing data and were removed from the sample. This resulted in a final sample of 438 service users. However, 36 service users did not respond to the item on current smoking status. As such, they will be excluded from this paper, leaving a final sample of 402. Ages ranged from 18-73, with a mean age of 38.9 years.

Results

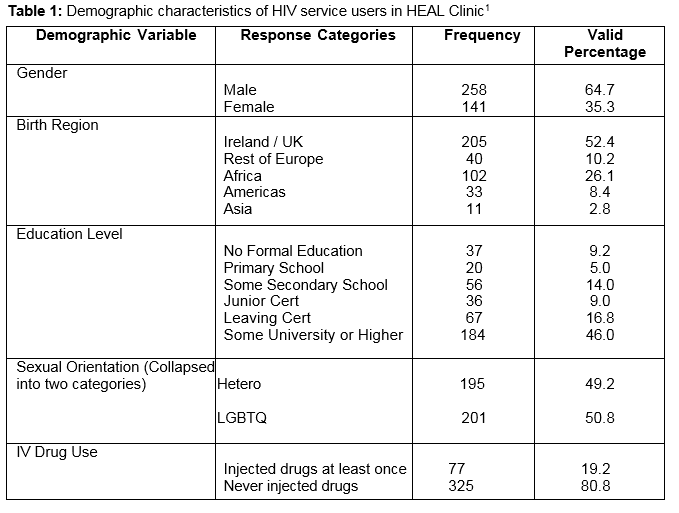

Table one presents a demographic overview of the service users accessing a free HIV clinic in Ireland. Two-thirds of the participants were males and just over half were born in Ireland or the UK. Over half (50.8%, n=201) identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, or ‘other’. Education levels among the sample were high, with nearly half (46.0%, n=184) having some college coursework or higher and an additional 16.8% (n=67) having completed the leaving cert exam. Another layer of descriptive analyses were conducted to explore sub-group differences in more depth, particularly around the categories recently highlighted as key subgroups of PLWHA where transmission rates remained elevated (sub-Saharan African women, IDUs, and MSM)1. When stratifying for gender, the data shows that 66.9% (n=170) of male participants self-identified as LGBTQ compared with only 21.6% (n=30) of female participants. Over half (55.1%, n=75) of women accessing the clinic were born in Africa and indeed, 70% of African service users accessing the clinic were female. Among men and women combined, 19.2% (n=77) had injected drugs in the past.

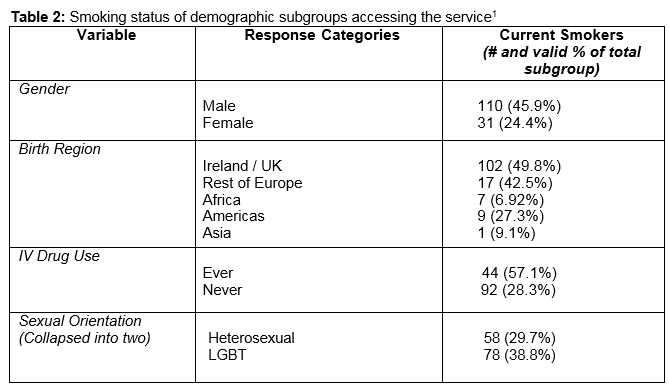

Of the total sample, 141 (35.0%) were current smokers and an additional 35 (8.2%) were ex-smokers. Among current smokers, 42 (24.4%) smoked between 1-10 cigarettes a day, 57 (33.3%) smoked between 11-20 cigarettes a day, and 30 (17.4%) smoked more than 20 cigarettes a day. Thus, the total prevalence of smoking among the sample was nearly double that of the general population in Ireland11. However, rates among key sub-groups were even higher. Table two illustrates the percentage of smokers present within various demographic subgroups accessing the service. As demonstrated, current smoking was high among males (45.9%), ever IDUs (59.7%), and service users born in Europe (43.3%). Comparatively, smoking prevalence was very low among African migrants (7.2%, 8) and extremely low among African-born women (1.3%, 1). Of smokers in the sample, 34.7% (n=41) were not planning to quit in the near future, 26.3% (n=31) were trying to quit the time of the survey and an additional 39.0% (n=46) believed they would be ready to quit in the next six months.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore smoking prevalence among a diverse sample of PLWHA in Ireland. It is also the first to provide a snapshot of the demographics of people accessing HIV/AIDS treatment at a public clinic in an urban area of Ireland. We estimate that the demographics of people accessing services in this clinic are similar to those reported in other major Western cities2-3. Furthermore, key subgroups of PLWHA recently reported in the literature including injecting drug users, young women from Sub-saharan Africa, and young men who have sex with men from Europe, Asia, and the Americas were all prominent in the treatment sample at this Irish clinic1. In line with international studies, smoking prevalence among PLWHA was nearly double that of the general population13, 15, 16. When looking in-depth at key sub-groups, discrepancies in prevalence became apparent. Current smoking rates among IDUs and MSM were more than double the general population, while smoking among African migrant women in the sample was close to zero. These findings come at a time when smoking in the general population in Ireland is at an all-time low12, making the need to address tobacco dependence among PLWHA all the more vital. A growing body of research reveals an increase in non-HIV related deaths among PLWHA, including tobacco-related moralities8, 25. As such, it is imperative that healthcare professionals and public health workers continue to address the need for smoking cessation services among PLWHA.

While prevalence in our sample was high, there was also a demonstrated desire to quit. Nearly two thirds of smokers expressed an interest in cessation and were either trying to quit or would be ready in the next six months. However, there are many challenges associated with smoking cessation treatment among PLWHA including an overlap between HIV/AIDS and substance use and mental illness, and high levels of stress and stigma-related discrimination15. Yet, there is also a widely reported desire to improve health outcomes13 and some trials have begun testing the efficacy of PLWHA-tailored smoking cessation programmes with varying success8,10,15. Now is the time for healthcare professionals and service providers to gain a solid understanding of the nature of tobacco dependence among subgroups of PLWHA, and consider incorporating elements of tobacco education and smoking cessation into their current service structure. Without effective smoking cessation programmes, thousands who benefit from advancements in antiretroviral treatment will go on to endure the consequences of tobacco-related disease and premature death.

Correspondence:

Kate Babineau

TobaccoFree Research Institute Ireland, DIT Kevin Street, Dublin 8

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the staff and participants at the clinic, as well as S Keogan, K Taylor, and A Burns for their assistance throughout the project. The TFRI would also like to gratefully acknowledge financial support from the RCDH Trust for this study.

References:

1. Beryer C, Karim QA. The changing epidemiology of HIV in 2013. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2013;8: 306-310.

2. Hamers FF, Downs AM. The changing face of the HIV epidemic in Western Europe: what are the implications for public health policies?The Lancet. 2004;364: 83-94.

3. De Cock KM, Jaffe HW, Curran, JW. The evolving epidemiology of HIV/AIDS.AIDS. 2012;26: 1205-1213.

4. Beryer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men.The Lancet. 2012,380: 367-77.

5. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. The Lancet. 2008, 372, 293-299.

6. Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage, LM, Schackman BR. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States.Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006,194: 11-19.

7. Wilson M, Husbands W, Makoroka L, Rueda S, Greenspan N, Eady A. Counselling, Case Management and Health Promotion for People Living with HIV/AIDS: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. AIDS Behav. 2012;17:1612-1625.

8. Nahvi S, Cooperman N. Review: The Need for Smoking Cessation Among HIV-Positive Smokers. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:14-27.

9. Petrosillo N, Cicalini S. Smoking and HIV: time for a change? BMC Medicine. 2013;11:16.

10. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014, 63:1108–12 [accessed 2015 Jan 22]

11. Hickey P, Evans, DS. Smoking in Ireland 2014: Synopsis of Key Patterns. Office of Tobacco Control, Health Service Executive. 2015.

12. Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100: 1896-1903.

13. Collins R, Kanouse D, Gifford A, Senterfitt J, Schuster M, McCaffrey D. Changes in health-promoting behavior following diagnosis with HIV: Prevalence and correlates in a national probability sample. Health Psychology. 2001; 20: 351-360

14. Shuter J, Bernstein S, Moadel A. Cigarette Smoking Behaviors and Beliefs in Persons Living With HIV/AIDS. Am J Hlth Behav. 2012; 36:75-85.

15. Gritz ER, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Amick BC, Arduino RC. Smoking behaviour in a low-income multi-ethnic HIV/AIDS population.Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6, 71-77.

16. Mamary EM, Bahrs D, Martinez S. Cigarette smoking and the desire to quit among individuals living with HIV.AIDS patient care and STDs. 2002; 16, 39-42.

17. Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States.New England Journal of Medicine. 2013; 368, 351-364.

18. Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. The Tobacco Atlas(No. Ed. 4). American Cancer Society. 2013

19. Turner J, Page-Shafer K, Chin DP, Osmond D, Mossar M. Adverse impact of cigarette smoking on dimensions of health-related quality of life in persons with HIV infection.AIDS patient care and STDs. 2001;15, 615-624.

20. Shuter J, Bernstein SL. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of non-adherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy.Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008; 10, 731-736.

21. Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Schneider MF, Gange SJ, Cohen M. Association of cigarette smoking with HIV prognosis among women in the HAART era: a report from the women’s interagency HIV study.American Journal of Public Health. 2006; 96, 1060-5.

22. CDC Global Tobacco Surveillance System Data (GTSSData). Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. 2013. Available:http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/gtssdata/Ancillary/DataReports. aspx?CAID=1. Accessed 2014 Jun 26.

23. World Health Organization. Tobacco questions for surveys: a subset of key questions from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS): global tobacco surveillance system. 2011.http://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/en_tfi_tqs.pdf. Accessed 4 Apr 2015.

24. Ware, JE. How to Score and Interpret Single-Item Health Status Measures: A Manual for Users of the of the Sf-8 Health Survey: (with a Supplement on the Sf-6 Health Survey). QualityMetric, Inc. 2001

25. Deeks S, Phillips A. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338(jan26 2):a3172-a3172.

P384