The Irish Language in General Practice in the Donegal Gaeltacht

J. Houston

School of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, G12 8QQ, Scotland.

Abstract

Aims

Irish (Gaeilge) has been in significant decline for many years. 1 This study sought to analyse patients’ opinion regarding the availability and use of the Irish language in general practices in the Donegal Gaeltacht. (N=100)

Methods

Questionnaires were provided by receptionist staff to consecutive adult patients attending three medical practices over a period of two weeks.

Results

Forty-six patients out of 100 surveyed were fluent native Irish speakers. Of these 46; 37 (80%) use Irish with general-practice staff, and 26 (57%) say Irish is their preferred language to discuss their health. The majority of patients (53%) do not know whether there are enough health services available in Irish.

Conclusion

The majority of native speakers prefer to use Irish when discussing their health. Many of these do not have access to Irish-speaking medical professionals. There is a lack of awareness among patients regarding services that are available. Potential improvement strategies could include interpretation services, language modules for healthcare professionals who wish to work in the Gaeltacht, the encouragement of healthcare professionals fluent in Irish to work in the Gaeltacht, and improved awareness of Irish language health services that exist already.

Introduction

The Irish language (Gaeilge) has been in decline for many years. 1 EU policy on endangered or minority languages recommends that support services should be provided to maintain Irish as a living, working, community language. 2 The Donegal Gaeltacht has a population of 24,744 with the highest concentration of Irish speakers found in the Gaoth Dobhair area. 3

There is evidence from the USA that Spanish speaking patients whose clinician speaks Spanish have significantly better compliance and satisfaction scores than with those whose clinician speaks English only. 4, 5 A Galway study shows that bilingual, native Irish-speakers’ scores in cognitive screening tests were significantly higher when the test was given to them through Irish. 1 This study examined patients’ opinion regarding the availability and use of the Irish language in general practices in the Donegal Gaeltacht.

Methods

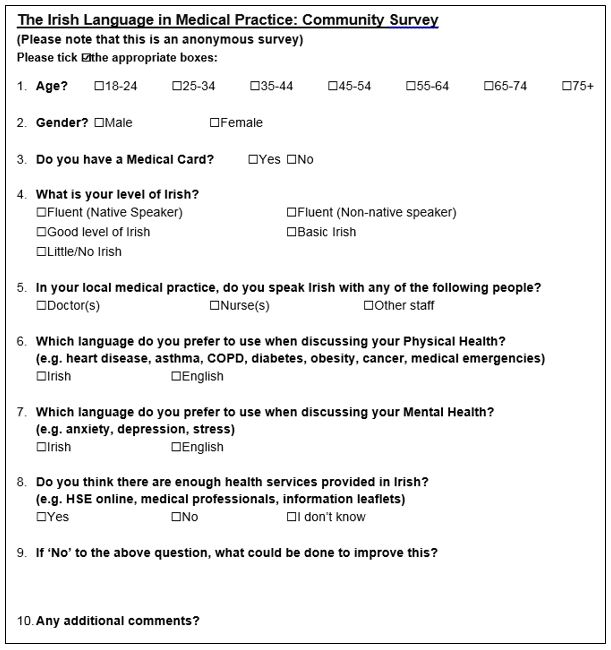

Questionnaires (Fig. 1) were distributed evenly to three medical practices in the Donegal Gaeltacht to be offered to adult patients consecutively by receptionist staff over two weeks in May 2018. Surveys were offered in Irish and English. 100 responses were collected and the data was compiled and analysed using Excel.

Figure 1: ‘The Irish Language in Medical Practice’ Survey (English language version)

Results

Out of 100 responses, 75 were female and 25 were male.

Of 5 patients over 75 years, 4 (80%) were fluent. All non-native fluent speakers were under 45. This may suggest that there is better education available, or that people moving into the Gaeltacht are encouraged to learn Irish more-so than previous generations. The highest rate of influency was seen between ages of 55 and 74. This may be due to in-migration of English-speaking retirees from outside the Gaeltacht and out-migration of native Irish speakers.

Overall, 50% of the population were fluent in Irish (46% of the population surveyed were native speakers and 4% had learned Irish). Of the 46 native speakers; 37 (80%) speak Irish with medical staff, and 26 (57%) say their preferred language to discuss health is Irish. This percentage was higher in Gaoth Dobhair (68%), the practice with the highest proportion of Irish speaking staff, suggesting that the availability of services may influence linguistic preference, as patients tend to communicate in the language that their healthcare provider is most comfortable with.1 The majority of patients (53%) do not know whether there are enough health services provided in Irish. However, 14 (54%) of those who prefer to use Irish to discuss their health believe there are not enough medical services provided in Irish and 9 (35%) do not know.

Discussion

Welsh studies suggest that the native language is often reserved for informal settings, whereas English tends to be used in formal and professional settings. Healthcare settings present a crossover in this sense. When patients feel stressed or vulnerable, they often revert to their first language.6, 7 It has been shown that patients are appreciative of linguistic sensitivity shown by healthcare professionals.4, 6

The present study highlights the importance of providing services in Irish. This is particularly important for older people who may revert to their native language in later life 7, especially if dementia develops.8, 9, 10

Other research suggests a number of recommendations for policy-makers, educators of healthcare professionals, and individual Gaeltacht practices:

Professional interpreters improve outcomes in diabetic, hypertensive and asthmatic management of patients whose first language is not used in practice. 4 (This is not always logistically possible however, and ‘ad-hoc’ interpreters are often used. This increases the risk of errors and breaches of confidentiality and autonomy.) 4

Another option is to offer Irish language courses to healthcare professionals and to encourage bilingual professionals to work in the Gaeltacht.

Most patients in the Gaeltacht are not aware of whether there are enough services available to Irish speakers. Improved awareness of the services available is needed in order to increase the acceptability of the Irish language in medical practice.6

Corresponding Author

Jack Houston,

Irishtown,

Upper Bohullion,

Burt, Lifford,

Co. Donegal,

Ireland.

Tel: 00353863246121

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

Ba mhaith liom buíochas mór a ghabháil leis na daoine seo a leanas as an chuidiú a thug siad domh:

Dr. Eamonn Coyle, Ark Medical Centre, Leitir Ceanainn, Co. Dhún na nGall

Dr. Edward Harkin, Bun Beag, Gaoth Dobhair, Co. Dhún na nGall

Dr. Des Gilmore, Ollscoil Ghlaschú, Albainn

Dr. Shaun O’Keeffe, Ollscoil na hÉireann, Gaillimh

Achan othar agus na baill foirne sna cleachtaí ginearálta i mBun Beag, Anagaire, Fál Carragh, Oileáin Thoraí, agus Leitir Ceanainn.

References

1. Ní Chaoimh D, De Bhaldraithe S, O'Malley G, Mac Aodh Bhuí C, O’Keeffe S. Importance of different language versions of cognitive screening tests: Comparison of Irish and English versions of the MMSE in bilingual Irish patients. European Geriatric Medicine. 2015;6(6):551-553. 2. 14. A European Charter for the Regional and Minority Languages in Europe. European Education. 1998;17(1):16-18. 3. Census of Population 2016 – Profile 10 Education, Skills and the Irish Language [Internet]. cso.ie. 2016 [cited 4 June 2018]. Available from: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp10esil/p10esil/ilg/ 4. JACOBS E, CHEN A, KARLINER L, AGGER-GUPTA N, MUTHA S. The Need for More Research on Language Barriers in Health Care: A Proposed Research Agenda. The Milbank Quarterly. 2006;84(1):111-133. 5. Carrasquillo O, Orav E, Brennan T, Burstin H. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(2):82-87. 6. Roberts G, Irvine F, Jones P, Spencer L, Baker C, Williams C. Language awareness in the bilingual healthcare setting: A national survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44(7):1177-1186. 7. Roberts G, Burton C. Implementing the Evidence for Language-appropriate Health Care Systems: The Welsh Context. Can J Public Health. 2013;104(6):88. 8. Appel R, Muysken P. Language Contact and Bilingualism. 2006. 9. Pan B, Gleason J. The study of language loss: Models and hypotheses for an emerging discipline. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1986;7(03):193. 10. Groot A. Language and cognition in bilinguals and multilinguals.

P844