What Really Matters to You? A Study of Public Perspectives on General Practice in Ireland

J. Brennan1,2, M. Bourke3, R. O’Donnchadha1, A. Mulrooney1

1.HSE Dublin/Mid-Leinster General Practice Training Programme

2.Royal College of Physicians of Ireland

3.Royal College of Surgeons/Dublin North-East General Practice Training Programme

Abstract

Aims

In recent years it has been recognised that person-centred care can lead to better outcomes for patients and a reduced burden on healthcare systems. The aim of this study was to explore what really matters to members of the public when they visit a GP in Ireland.

Methods

This qualitative study used a structured interview methodology with one question; “What really matters to you when you go to see a GP?” Results were analysed using an integrated approach, involving both inductive and deductive methods.

Results

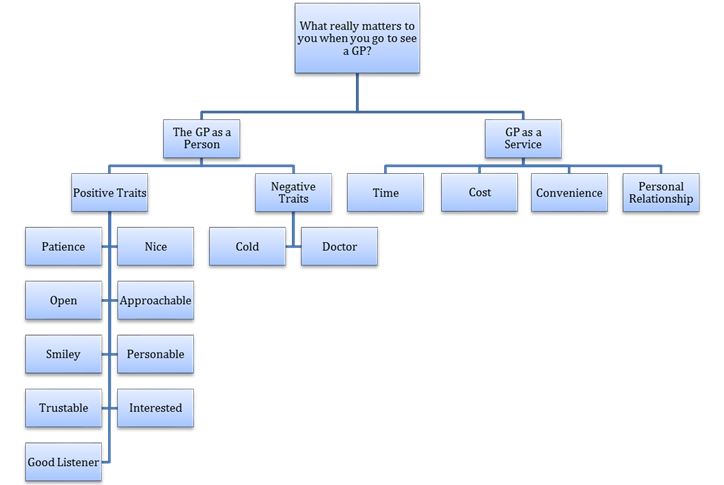

Responses from the 10 study participants were subdivided into two overarching themes: the General Practitioner as a person and the General Practice as a service. Personality (open, approachable, personable, trusted, interested) and service (time, cost, convenience, personal relationship) traits matter to patients.

Conclusion

Patients must be facilitated and encouraged to voice what really matters to them in order to inform truly person-centred healthcare improvement.

Introduction

Traditionally, health services were designed to provide care to the majority. Resources, feasibility and other provider-centred concerns determined services offered to patients. In recent years it has been recognised that providing more tailored individual care can lead to better outcomes for patients and a reduced burden on the healthcare system. This is particularly important in the context of an aging population with increasing multimorbidity. In addition to this, there has also been a drive internationally towards increasing the quality of healthcare provided1.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (US) published ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century’. Six domains were defined in order to inform aims for improving quality and indicate that healthcare should be safe, effective, efficient, timely, equitable and patient centred. They define patient centred care as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”2.

The Picker/Commonwealth Program coined the term ‘patient centred care’ in 1988. Subsequently, the Picker Institute described 8 principles of patient centred care3. The broad array of person-centred care components involves many behaviours, activities and concepts. In place of an inevitably limited concise definition, the Health Foundation in the United Kingdom has adopted a framework to guide person-centred care comprising of four principles4: affording people dignity, compassion and respect; offering coordinated care, support or treatment; offering personalised care, support or treatment; and supporting people to recognise and develop their own strengths and abilities to enable them to live an independent and fulfilling life.

To date, this complex domain of quality in healthcare has proven difficult to measure and there is no one all encompassing internationally recognised measure for person-centred care1. In Ireland, the Health Service Executive commits to improving patient experience and outcomes through it’s ‘Framework for Improving Quality in our Health Service’. This framework recognises person-centredness as a key element of quality and establishes ‘Person and Family Engagement’ as a key driver for improving healthcare quality through involving patients in the design, planning and delivery of all care5.

As part of overall health systems, international evidence suggests that primary care contributes to overall health system performance and health through quality of care, efficiency of care, equity in health and greater economy in the use of resources6,7,8. In Ireland, General Practice represents a key element of primary care. There are over 25 million consultations between patients and GP’s in Ireland each year, with patients on average visiting their GP 5.17 times per year9.

In 2007, the HSE published it’s first large scale representative survey of consumer satisfaction across all elements of the health service, including General Practice. For overall quality of care, 84% of General Practice patients rated their experience as excellent or very good, placing it ahead of inpatient, outpatient and other community services. Indeed responses regarding General Practice compared favourably to these other Irish healthcare settings across all 8 domains surveyed10. More recent evidence suggests that those most satisfied have positive personal experiences with a GP that is easy to access11.

At present, healthcare in Ireland and particularly General Practice are facing immense challenges in order to meet patient’s needs. In meeting these challenges, it is essential that providers strive for improvements in quality. In order to maximise these improvements, it is essential that the patient voice is at the heart of informing what person-centred General Practice looks like.

In their noteworthy New England Journal of Medicine article in 2012, Michael Barry and Susan Edgman-Levitan espoused the opinion that we must view the healthcare system through the patients’ eyes to become more responsive to patient’s needs. They proposed achieving this by learning how to ask ‘what matters to you?’12 The aim of this study was to explore what really matters to members of the public when they visit a GP in Ireland.

Methods

This qualitative study used a structured interview methodology. The study design aimed to explore public perceptions through qualitative responses to a single question. The sample size for this project was 10 participants. This sample size was chosen to allow for a broad array of responses to be collected and analysed within the timeframe and resources available to complete the study.

Participants were recruited by approach at one public urban street location, without proximity to a healthcare facility. Study participants were not known to the researchers. All members of the public meeting the inclusion criteria were considered for recruitment until the sample size was reached. Any member of the public over the age of 18 capable of providing consent and engaging in an interview was deemed eligible for inclusion in the study.

Participants that provided written consent to participate in the study, were then asked one question. The question posed was; “what really matters to you when you go to see a GP?”. Participants were given the opportunity to first consider the question and then to provide an immediate response. Interviews ranged from 6 to 49 seconds in length (median 16 seconds).

Data was collected by video in order to maximise the quality and impact of participant responses. The lead researcher analysed the data using an integrated approach, involving both inductive and deductive methods. A coding structure was applied with three distinct streams; conceptual codes, relationship codes and participant characteristics. The conceptual coding applied allowed themes to emerge from the participant interview responses in an inductive fashion.

This study was granted full ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the Irish College of General Practitioners.

Results

Taxonomy

Sample

6 study participants were male and 4 were female. Responses from the 10 study participants could broadly be subdivided into two overarching themes: the General Practitioner as a person and the General Practice as a service.

General Practitioner - The Person

Responses categorised as relating to the General Practitioner as a person focused mainly on positive and negative personality traits and attributes. Five participants highlighted positive qualities that they would find desirable in a GP, specifying that it matters to them if the GP is patient, open, smiley, nice, approachable, trustable and interested. Two participants drew on negative conceptions of traits, ‘cold’ and ‘doctor’, to illustrate a desire for more personable characteristics that they would value in a practitioner.

The capacity of the GP to listen attentively and effectively also featured prominently in interview responses. Participant 7 linked this to both the “manner” of the GP and how this can affect outcomes, in her case by unearthing “what the real problem is”. Many of the positive personality traits emphasised, such as “approachable”, “interested”, “open” and “patience” refer to characteristics that are associated with and may encourage open receptive communication.

Indeed “being a person not a doctor”, and creating this separation of self from professional was highlighted by participant 6 as being a key element in order to establish meaningful communication and to facilitate meaningful reassurance. This would suggest that personability on the part of the GP plays not only a role in approach, rapport and communication, but may also have a therapeutic dimension.

In several cases participants linked the idea of attending or interacting with a personable GP to familiarity, connection and comfort. These links were established in a positive spirit and given the frequency with which this sub-theme recurred, and the relationship that can be drawn between a personable GP and General Practice as personable service, it appears from this data that this is highly important to patients.

Several participants discussed personability both from the perspective of desirability as an individual personality trait and also how it is related to the service provided by a GP. “It’s important to be known” as Participant 8 put it. For Participant 9, learning “to connect” with him and giving “a good service” were coupled together as being paramount. Participant 3 suggested that “time slot(s) in the day” and “trying to turn around a long patient list” may conflict with being personable, and as a result could cause the patient to feel that they are ‘inconveniencing” the doctor. She also implied that this may impact on whether or not the patient feels that they can “trust” the doctor. In a similar vein, Participant 6 also alluded to how the dynamic between GP workload and time may be at odds with creating a “comfortable” and “personal” setting for the doctor-patient interaction.

General Practice - The Service

The wider service provision issues expressed by participants during interview also included cost, convenience and time. Participant 2 disclosed a wish for “more affordable doctors”. Participant 5 equated patients to customers and raised the concept of convenience. He offered the view that General Practice should be open when the patient needs it. In doing so, he also alluded to the element of time, and “not having to wait” to see a doctor. It was strongly stated by Participant 10 that being seen “at the appointed time”, or being provided with a “reasonable explanation as to why the delay” if not, was an important facet of care.

Indeed, time was an element in half of all responses, not only in it’s relationship with personability and it’s bearing on when the service is provided, but also it’s impact on what service can be provided within it’s constraints. The idea that the service may be rendered incomplete due to inadequate time was raised by Participant 1. For her, it was important that the GP have time to answer her questions after taking the time to pose their own. Participant 3 stated a desire not to be defined by or treated as “just a 15 minute time slot during the day”. Gender did not appear to have a bearing on what really matters to this cohort of people when seeing a GP with both sexes expressing views relating across all of the emergent themes.

Discussion

When asked ‘what really matters to you when you go to see a GP?’, participants expressed views on positive and negative traits in the indiviidual GP, and in the service they provide. In viewing these results through the lenses of the Picker Institute Principles of Person-Centred Care, or the Health Foundation guiding framework for providing Person-Centred Care, it is evident that many of the themes that emerged during interview with this cohort of participants are echoed through these international guidelines. For example, it is unlikely that a patient could be approached and treated with a combination of dignity, compassion, empathy and respect without a degree of personability on the part of the GP and service. The ‘personable’ factor is also likely to foster a doctor-patient relationship that enables a greater possibility of self-support and care through shared recognition of individual strengths and abilities. In addition, familiarity between patient and GP is undoubtedly an essential contributor to continuity and ongoing coordination of care.

Interestingly, none of the participants in this study overtly attached importance to correct diagnosis and effective treatment of illness, although this may have been inherent in how some participants referred to the work of the GP or service. However, this study demonstrates that members of the Irish public prioritise particular elements of person-centred care as it applies to General Practice. This study suggests that timely access to a familiar, personable General Practitioner, with the ability and capacity to listen, while continuing to provide an efficient service is paramount to the Irish public. In the context of the wider health and social care system in Ireland at present, these findings are important, and complement previous research in this area using varied methodological approaches11.

Possible strengths of this study include it’s open approach to asking members of the public about their preferences in GP care. By framing these perspectives through asking ‘what really matters to you’, answers can be viewed and analysed in an inductive way, thus allowing the true voices of service users to be heard. Weaknesses include a relatively limited sample, in both size and representative composition. In addition, very limited quantitative data was captured, possibly limiting the generalisability of the results of this study.

Professional and academic bodies representing General Practice advocate for a health system that supports comprehensive, equitable, coordinated, well resourced and continuous care in the community13. This is underpinned by the WHO Alma Ata Declaration (1978)14. While healthcare policy in Ireland has been slow to date to reflect this, there is now a political will to move towards a more community oriented healthcare system15. Without engaging patients comprehensively in this process, there is a high risk that healthcare in Ireland will remain unfit for the purpose for which it is supposed to serve; caring for individual people. In navigating this extensive and challenging transition, patients must be facilitated and encouraged to voice what really matters to them.

These qualitative participant responses and resultant themes provide rich and valuable perspectives in the context of Irish General Practice today. General Practice in Ireland is facing a multitude of financial, social and organisational challenges moving into the future. Further research in this area should be prioritised to continously guide the evolution of General Practice. Ongoing neglect of the core principles of person-centred care, and their potential to drive improvements in the quality of healthcare provided in the community risks having a profoundly detrimental effect on General Practice moving forward, and would represent a missed opportunity for the next generation of patient in Ireland to be cared for based on what really matters to them.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare in relation to funding provided for this research.

Corresponding Author

Dr. John Brennan, General Practitioner and Healthcare Quality Improvement Faculty with the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland.

Email: [email protected]

References

1. De Silva. Helping Measure Person Centred Care. The Health Foundation. www.health.org.uk/publication/helping-measure-person-centred-care. March 2014.

2. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America and Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press March 2001.

3. Picker Institute Europe. www.picker.org/about-us/principles-of-patient-centred-care. Downloaded January 2017.

4. Person-Centred Care Made Simple: What everyone should know about person centred care. The Health Foundation. October 2014. http://www.health.org.uk/publication/person-centred-care-made-simple. Downloaded May 2017.

5. Framework for Improving Quality in Our Health Service. Health Service Executive Quality Improvement Divivion. April 2016. http://www.hse.ie/eng/about/Who/QID/Framework-for-Quality-Improvement/ Dowloaded May 2017.

6. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. (2005) Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q; 83:457–502.

7. Kringos DS, Boerma WG, Hutchinson A, van der Zee J, Groenewegen PP. (2010). The breadth of primary care: a systematic literature review of its core dimensions. BMC Health Serv Res;10:65.

8. Starfield B. (2012). Primary care: an increasingly important contributor to effectiveness, equity, and efficiency of health services. SESPAS report. Gac Sanit. 2012 Mar;26 Suppl 1:20-6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.10.009. Epub 2012 Jan 21.

9. Behan W, Molony D, Beamer C, Cullen W. (2013) Are Irish Adult General Practice Consultation Rates as Low as Official Records Suggest? A Cross Sectional Study at Six General Practices. Ir Med J. 2013 Nov-Dec;106(10):297-9.

10. Insight 07: Health and Social Services in Ireland – a survey of consumer satisfaction. Health Service Executive. 2007. http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/Your_Service,_Your_Say_Consumer_Affairs/Reports/Insight_07.html. Downloaded May 2017.

11. O’Dowd T, Ivers J, Handy D. (2017) A Future Together – Building a Better GP and Primary Care Service. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/news/media/pressrel/hse-launches-report-a-future-together-building-a-better-gp-and-primary-care-service.html. Downloaded October 2018.

12. Barry MJ and Edgman-Levitan S. Shared Decision Making – The Pinnacle of Patient Centred Care. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:780-781 March 1, 2012. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283.

13. General Practice is Key to Sustainable Healthcare. Irish College of General Practitioners Submission to the Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Health Care. August 2016. https://www.icgp.ie/go/about/policies_statements/2016/8E702DE0-D505-6CD8-B15B21B634822728.html. Downloaded May 2017.

14. WHO. Declaration of Alma- Ata. (1978). (Downloaded from http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf?ua=1 on 21st February 2017)

15. Sláintecare Report. Houses of the Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Healthcare. May 2017. http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/oireachtasbusiness/committees_list/future-of-healthcare/reports/. Dowloaded May 2017.

P854