When do we think it is Safe to Drive after Hand Surgery? – Current Practice and Legal Perspective

SF Murphy1, JD Martin-Smith1, W Martin-Smith BL2, E O’Broin1, AJP Clover1

Department of Plastic Surgery, Cork University Hospital, Cork1

The Law Library, Four Courts, Dublin2

Abstract

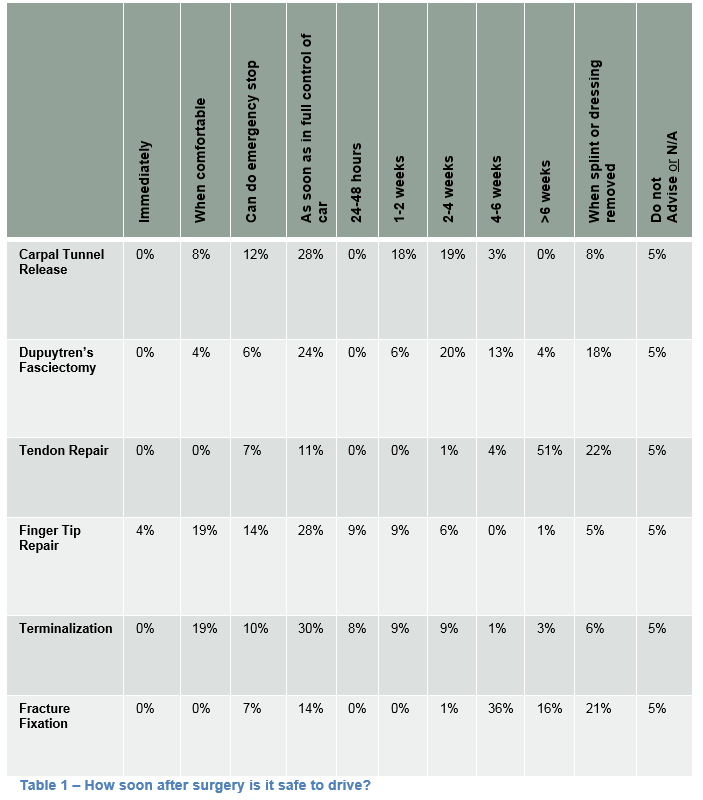

Patients recovering from hand surgery frequently ask when it is safe to drive and it is unclear where the responsibility lies; the surgeon, the patient or the insurance company. An eight-question survey looking at various aspects of clinical practice was circulated to consultant and trainee plastic and orthopaedic surgeons in Ireland and the UK. Of the 89 surgeons who replied, (53%) felt the decision when to drive was the patient’s compared with the insurance company (40%) and the surgeon (7%). 80% advised patients to contact their insurance company. 87% were unaware of current regulations or guidelines. National guidelines were vague and left the decision with the treating doctor. Similarly, major insurers advise patients to contact their doctor for advice. From a legal standpoint, the patient has a duty of care to other road users to be in full control of his vehicle prior to driving, regardless of any advice received.

Introduction

Hand and wrist injuries are common and make up approximately 20% of emergency department visits1 and up to two thirds of the trauma workload of a plastic surgery unit2. Hand surgery often produces a temporary variable dysfunction that depends both on the extent of the procedure and the individual’s recovery. This may affect driving performance. It is relatively clear about how to proceed after permanent disability3,4, but what to do after temporary incapacity is less clear; as is who should decide when the incapacity is no longer likely to be detrimental to the ability to drive a car5. This has safety, financial and social implications for the patient. Patients also want to know whether or not their insurance would be valid if they were to have an accident. This makes a seemingly innocuous and commonly-asked question a potential medico-legal hazard.

There are three principal stakeholders involved in deciding when a patient can safely resume driving after hand surgery: the patient, the doctor and the insurance company and it is unclear where responsibility ultimately lies. This lack of clarity leaves all parties exposed in the event of an accident and is an issue that urgently needs to be addressed.This study sought to illustrate current practice amongst Plastic and Orthopaedic Surgeons in Ireland and the UK, examine existing guidelines relating to driving after hand surgery and the current legal position and the position of the major insurance companies.

Methods

This study addresses three key areas. Firstly, current practice and knowledge amongst surgeons was surveyed; secondly, existing guidelines and insurance company policies were examined; and finally, professional legal counsel was sought. The survey consisted of eight questions, which was circulated to members of the Irish Association of Plastic Surgeons (IAPS), the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS), PLASTA UK and all Orthopaedic Surgery consultants and trainees in Ireland. Questions included how soon patients are safe to return to driving following a number of different common surgical procedures, who is responsible for making this decision, awareness of any current guidelines and if further guidelines are necessary (see Figure 1).

Five major insurers were contacted; AXA, Aviva, the AA, Allianz and AIG. A customer representative of each company was contacted by telephone and asked what advice they would give to a person recovering from hand surgery with regards to returning to driving and validity of insurance. A practicing barrister-at-law based in Dublin and co-author of this article performed a comprehensive search of the legal literature, looking specifically for any precedence relating to driving after surgery and to establish where the legal responsibility lies for the decision of the patient returning to driving. A concise summary of the legal issues involved is also provided.

Results

There were a total of eighty-nine responses to the survey circulated to Plastic Surgeons and Orthopaedic Surgeons in Ireland and the UK (see Figure 1). The majority of responses were from the UK (57%), followed by Ireland (40%) and the US (3%). Consultants (36%) and Specialist Registrars (39%) represented the majority of participants, followed by Registrars (15%) and SHOs (10%).

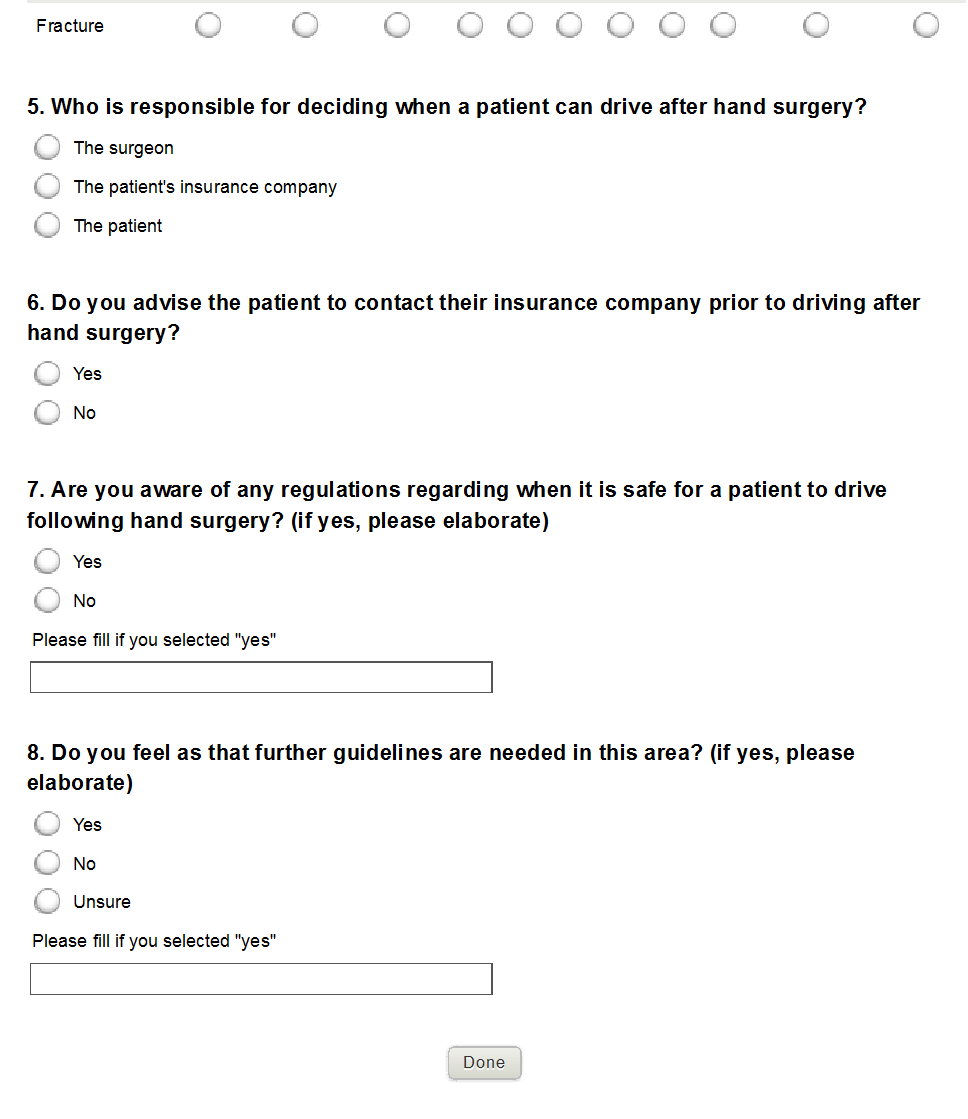

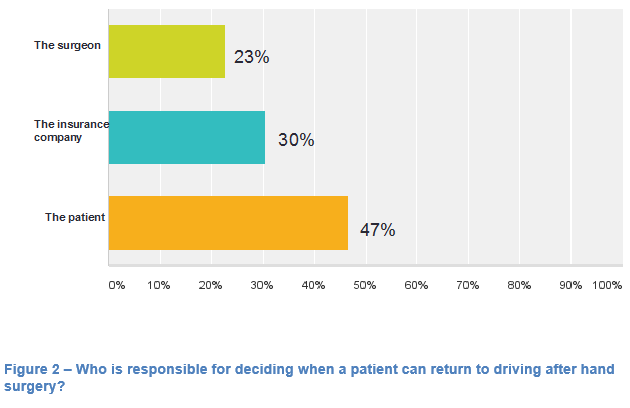

Following tendon repair, 51% advise patients that they may return to driving after six weeks and 22% after the splint has been removed (see Table 1). After fracture fixation, 45 (51%) advised them to return to driving after 4-6 weeks, 14 (16%) after 6 weeks and 19 (21%) after removal of splint. Of note, 5% of surgeons offer no advice to patients following any procedure.

Figure 1 – Survey

Only 9 (10%) participants were aware of any current guidelines relating to this area. Sixty-six (74%) felt that guidelines were necessary, 15 (17%) felt they weren’t necessary and 8 (9%) were unsure. The majority of surgeons (42, 47%) felt that it was the patient’s own responsibility to decide when to resume driving (see Figure 3). The majority (67, 75%) also advised patients to contact their insurance company prior to returning behind the wheel of a car.

Only 9 (10%) participants were aware of any current guidelines relating to this area. Sixty-six (74%) felt that guidelines were necessary, 15 (17%) felt they weren’t necessary and 8 (9%) were unsure. The majority of surgeons (42, 47%) felt that it was the patient’s own responsibility to decide when to resume driving (see Figure 3). The majority (67, 75%) also advised patients to contact their insurance company prior to returning behind the wheel of a car.

The current guidelines from the Irish Road Safety Authority (RSA)4 make no reference to any surgical procedures and make no recommendations regarding when it is safe for an individual to resume driving. They suggest that the time taken for a patient to return to drive after any medical procedure “should be determined by the treating health professionals”. The Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) guidelines from the UK3 also do not refer to specific surgical procedures or suggest lengths of time to return to driving. They state “Licence holders wishing to drive after surgery should establish with their own doctors when it is safe to do so”. It goes on to say that “It is the responsibility of the driver to ensure that he/she is in control of the vehicle at all times”. This places the responsibility primarily with the surgeon but also with the patient. The Medical Protection Society guidance document on assessing fitness to drive6 states that it is the responsibility of the doctor to “assess your patient’s fitness to drive and recommend restrictions and ongoing monitoring”. Essentially, the decision appears to fall to the surgeon in the eyes of the RSA and the MPS documentation, however no guidelines exist to enable surgeons to make reliable, reproducible, and legally sound assessments. When customer representatives from five major insurance companies were contacted for advice, they unanimously recommended that the patient should contact the treating surgeon and obtain either verbal or written clearance prior to returning behind the wheel. None of the companies contacted have specific protocols for patients who have undergone surgery.

From a legal standpoint, a doctor in Ireland does not have any statutory duty to inform a patient that he should not drive until an injury has healed. However, a duty may arise under the law of negligence. A long standing principle of the law of negligence is that a person owes a prima facie duty of care to those people with whom there is a sufficient relationship of proximity or neighbourhood, such that carelessness on his part may be likely to cause damage to those people7. A doctor’s duty of care may extend beyond the patient to a wider class of people who are owed a duty arising out of the doctor-patient relationship8. Such a class of people may include other road users coming into contact with the patient on his return to driving. The exercise of a doctor’s duty of care would encompass advice given regarding a patient’s ability to drive. Negligent or careless advice may invite liability in the same way negligent or careless treatment may attract liability.

Whether a duty of care exists or not, in order to be liable, a person must have caused injury to that victim by reason of his negligence. If a patient causes a road accident, a court may have to decide whether the treatment of the hand injury and related medical advice (or lack thereof) caused the accident. In such circumstances, the courts would also examine whether an intervening act had occurred which could be considered an independent act so as to break the chain of causation of the injury complained of. In coming to its decision, the courts will examine the forseeability of the intervening act and the state of mind of the driver patient. While it may be foreseeable that a patient may decide to drive even with an injury, if that person knows that he is incapacitated, the decision to drive will be, to some degree, a careless or reckless one.

Any driver has a duty of care to all other road users to take such care of other road users as is reasonable in the circumstances. The duty of care encompasses a number of elements including the duty to drive with due skill, care and attention. Separately to this general duty of care to other road users, a driver has statutory duties,

(i) “not to drive or attempt to drive a mechanically propelled vehicle in a public place when he is, to his knowledge, suffering from any disease or physical or mental disability which would be likely to cause the driving of the vehicle by him in a public place to be a source of danger to the public” 9, and

(ii) “not to drive a vehicle in a public place without due care and attention, or without reasonable consideration for other persons in that public place”10.

A driver, incapacitated by a hand injury, may be limited in his ability to use the controls of his vehicle. That driver’s decision to drive despite being unable to fully control his vehicle, is a reckless or careless act which could be said to break the chain of causation for the accident which causes injury. Despite being aware of the risk caused by his limited mobility, the driver decides to drive anyway and thus causes the accident complained of. Unless there are factors which conceal the physical impairment to the patient (e.g. a medication which causes drowsiness unknownst to the patient), a warning from a doctor not to drive could only tell the patient that which a reasonably prudent driver ought to know himself. Ultimately, it is a driver’s responsibility to be in control of his vehicle so as to meet his statutory obligations as well as his duty of care to other road users. A doctor can give guidance but a patient cannot abdicate this responsibility. Legally, the responsibility ultimately rests with the patient, who has a duty of care to other road users and must ensure that he/she feels comfortable and in control of the car before driving.

Discussion

Advising patients when to drive after hand surgery is a very difficult task for surgeons. It is littered with uncertainty and is lacking in both guidelines and legal precedence. It is discussed on a regular basis with patients despite this lack of knowledge and guidance. Overall, there is a lack of both evidence in the literature and guidelines11. Our review of the motoring guidelines in Ireland and the UK shows that this has yet to be addressed by government authorities. They defer to the opinion of the treating surgeon for all post-operative guidance. Similarly, insurance companies advise all patients to speak to the surgeon. In contrast, 75% of surgeons advise patients to speak to their insurance company.

In legal terms, the responsibility lies with the patient who must be able to demonstrate that he/she is in full control of the vehicle if stopped by the police5. The doctor is unlikely to be held responsible for an accident arising from the patient’s impaired ability to drive unless the patient’s decision to drive arose from careless or negligent advice on the part of the doctor. Each patient has a duty of care to other road users and must ultimately take responsibility for their own ability to fully control the vehicle. Our survey revealed a wide range of practices amongst the surgical community when it comes to advising patients. There were no clear patterns of advice given apart from tendon repairs and fracture fixations which both have well defined post-operative periods of splinting and rehabilitation. A similar study that looked at advice given by consultant general surgeons to patients post inguinal hernia repair regarding when they can return to driving showed inconsistent advice, ranging from the day of surgery to two months after surgery12. Plastic and orthopaedic surgeons also showed little consistency in the advice they give to patients.

This study highlighted an urgent need for comprehensive guidelines in this area that address specific procedures. 90% of surgeons were unaware of any guidelines and 74% felt that they were needed. While the legal responsibility rests primarily with the patient/driver, there is also a responsibility for doctors to provide patients with some guidance. The MPS guidelines, although very non-specific, do advise that the treating doctor “assess your patient’s fitness to drive and recommend restrictions and ongoing monitoring”6. At present they are ill equipped to fulfill this role and a joint guideline involving the Irish Association of Plastic Surgeons, the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons, the Irish Hand Surgery Society and the British Society for Surgery of the Hand would be of significant benefit. However, ensuring that patients are aware of their own responsibilities is also paramount.

Correspondence:

Stephen Murphy, Department of Plastic Surgery, Cork University Hospital, Cork

Conflict of interest statement:

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Putter CE De, Selles RW, Polinder S, Beeck EF Van. Economic Impact of Hand and Wrist Injuries : J Bone Jt Surg. 2012;56(9):1–7.

2. Abdelhalim MA, Chatterjee JS. The operative trauma workload in a plastic surgery tertiary referral centre in Scotland. Eur J Plast Surg. 2012;35:683–8.

3. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. For medical practitioners At a glance guide to the current medical standards of fitness to drive Drivers Medical Group. 2014;

4.Road Safety Authority. Sláinte agus Tiomáint - Medical Fitness to Drive Guidelines. 2014;(April).

5. Nuñez V a., Giddins GEB. “Doctor, when can I drive?”: An update on the medico-legal aspects of driving following an injury or operation. Injury. 2004;35:888–90.

5. Medical Protection Society. Assessing a patient’s fitness to drive. 2013;(December):1–2.

6. Lord Wilberforce in Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1978] AC 728 at 751. That decision has been followed in Ireland in cases such as Ward v McMaster [1988] IR 337, Glencar Explorations plc v Mayo County Council (No 2) [2002] 1 IR 84.

7. Pittman Estate v Bain (1994) 112 D.L.R. (4th) 257 in which a claimant successfully argued that a doctor was liable for her contracting HIV from her husband because the doctor had failed to warn her husband of his HIV condition.

8. Section 48 of the Road Traffic Act, 1961 as amended.

9. Section 52 of the Road Traffic Act, 1961 as amended.

10. Kalkur S, McKenna D, Dobbs SP. “Doctor - when can I drive?” - Advice obstetricians and gynaecologists give on driving after obstetric or gynaecological surgery. Ulster Med J. 2007;76(3):141–3.

11. Ismail W, Taylor SJC, Beddow E. Advice on driving after groin hernia surgery in the United Kingdom : questionnaire survey. Br Med J. 2000;321(June):2000.

P484